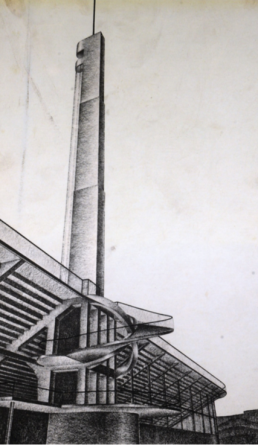

To be fitted to modern standards, the Franchi stadium in Florence needs from along time to cover the bleachers, bring the public of the curves closer to the play field, and add the accessory functions today required for an international level plant. Thus, in recent times, the Fiorentina soccer club solicitations have led the City Administration to face a difficult situation due to the problems of protecting the monument. As known, indeed, the work of Pier Luigi Nervi is an undisputed masterpiece of modern architecture, in particular for its famous curved staircases, the Marathon tower and the shelter of the grandstand.

To solve this thorny issue, in which is even on sight the club exodus to another municipality, Mayor Nardella set up an international competition whose results however don’t seem to gain a general consent: there are many negative judgments, expressed not only by the hard to please Florentines, polemists as usual, but also by very balanced and qualified people, whose opinions cannot be dismissed as unmotivated or preconceived. Something really seems to be going wrong on this way, and Florence, after having lost Michelucci’s Station image, cannot afford to burn out another of the very few 20th century architecture masterpieces that the city can still boast of (in addition to these, Fagnoni’s Air Warfare School and Mazzoni’s Railways Power Plant).

The issue is therefore serious, and the administration cannot make an ostrich policy by hiding behind the reports of the contest: we might hear something as “operation successful, but patient dead”.

In order to look at this tricky situation in a constructive key, we must first of all remember that in the initial step of such competitions only outline ideas are presented, and that these ideas will be defined without distortions in the subsequent executive project. So, I’ll make now some personal remarks, even if some topics are difficult to explain by words only, because when talking about architecture we should draw, as when talking about music we have to play.

The most distinguish element in the Arup project is the roof, which, in order not to touch Nervi’s structures nor to stand out in the panorama, has been conceived (I’m quoting the project card) as “a thin rectangular metal blade [that] levitates above the historical stands of the Stadium”. This description appears to be a bit tinged with optimism, given that inside smooth metal sheaths are hidden structures of steel trusses that can cover more than 8 acres (soccer field excluded) at a height of 82 ft (Nervi is at 62), resist to winds, snow, accidental loads and terrorist attacks, and support 160 ft overhangs, photovoltaic panels, lighting systems, maintenance walkways, and even two long stands with skyboxes hanging down from it on the Marathon side.

It will be interesting to see what modifications will be made to this structures in order to adapt it to the anti-seismic and safety current rules; and to avoid complications or delays in the programs, it could be extremely useful for the Municipality a timely confrontation with the Civil Engineering and the Fire Departments, which do not seem involved in the preliminary steps of the competition.

But the protection of the monument is not matter of standards and measures only. From a perceptual point of view, this plate will not seem levitating, but looming over the stadium. The Franchi (before ‘Berta’) is born as a dilated proportions space, wide and open, with the view of Fiesole and the hills, and the tower of Maratona soaring into the sky, and the character of a space is also a value to be protected, as was evident to everyone watching, for example, some recent artistic performances in Piazza della Signoria. But in the Arup project (and not only in it) Nervi’s space is no longer found, even if its main elements – tower, stairs, shelter – still remained there: an image of exteriors became an image of interiors, and a rather cold one.

And in front of the objection that it was impossible to do otherwise, since the two new transversal grandstands would close the perimeter all around the soccer field, the answer is no: maintaining a visual relationship with the landscape references was possible if other types of roofing were designed. In order to innovate the monument while respecting it, in short, there was a narrow but practicable way to follow, named measure and essentiality, that is the Nervi way. He with few resources created essential but very iconic structures, well knowing that ‘genuine’ structures are beautiful, and have to be shown.

The Arup project offers matter for reflection also on other topics concerning the protection of architecture, but here, in order not to generate misunderstandings, it is necessary first of all to clarify that adjustments are necessary also for monuments, to avoid that their functionality may be lost, because a building without functionality dies, and what was architecture becomes archaeology. For these adjustments, no imitation of what already exists is suitable: it is necessary to create, to innovate, but humbly and respectfully, in a way balanced and coherent with the values to be protected, and this way consists essentially in using an appropriate architectural language, whose words are geometries, proportions, calibrated materials, and, precisely, also a sense of measure, so that the new image does not obscure the one to be protected. And here it is clear that, beyond the legitimate diversity of forms, Arup and Nervi do not speak the same language.

Was it possible to make a roof that didn’t overpower the image of Nervi? Yes, all the way: today many stadiums have beautiful lightweight roofs, made with new materials that offer incredible and innovative possibilities, and also in respect of the environment. Structures of this type, responding in substance to Nervi’s lesson, could allow to maintain that sense of open air that characterizes the stadium and to give oxygen to the tower, the canopy, the stairs – that not by chance are round. From what I could see, however, no one followed this track, perhaps fearing that lightness and minimalism would not be appreciated. And yet the ancient builders had pointed out this solution: “Et vela erunt” we read on the walls of Pompeii, that is ‘Come people to the amphitheater, today we’re going to pull up the veils, no sunburns!’. So here’s the suggestion: light, mobile covers, en plein air, as also on the Colosseum. Two thousand years ago.

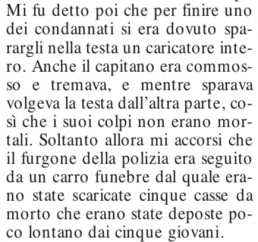

But in the end I would add a note of great bitterness about another type of protection. In the contest call there was no suggest about maintaining a respectful remembrance, as there still is, of the five young men shot at the stadium wall in ’44. Why?

That strikes me as a very bad signal, and Arup has nothing to do with it.

Right: drawings of the Marathon tower with the helicoidal staircase and of the covered tribune (1930; Florence Municipality, documentation of the competition announcement); example of Eclipse membrane roofing; retractable roofing of the Olympic Stadium in Rome; testimony of Luigi Bocci in: M. Piccardi and C. Romagnoli, Campo di Marte, La casa Usher, 1990.