Two Roman marbles pique the curiosity of visitors to the Baptistry. One is a walled bas-relief on the southern façade of the scarsella, at the bottom, which depicts two scenes: one of trade and the other of a grape harvest. On the left we see an anchored cargo ship with some men who are unloading some merchandise, and on the right other men who are crushing grapes in vats. Therefore, it does not concern a naval battle as naively guessed by some.

It was also thought that the grape was a reference to the Eucharist, given that the marble is in a religious building, but this interpretation seems far-fetched.

So, let’s move on to more objective observations.

By looking at this marble carefully we understand that the slab was originally longer, and that it was then cut (rather badly) in three parts, two of which are those that are seen now and that, when juxtaposed, have the right width to be inserted into the layout of the façade’s cladding. The third piece was thrown away, and this means that the scene depicted in the bas-relief didn’t interest anyone, and that the workers only cared about having a valuable marble piece and that it had to be the exact size for what they wanted to do.

Was it a place-marker for a burial? It doesn’t exactly look like it, considering the quality of the handiwork, the depicted scenes and the lack of any writing; and then in that case they could have done something less complicated and without having to deal with the layout of the cladding of the wall.

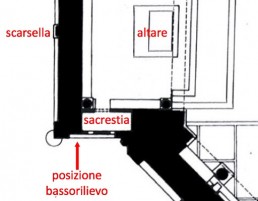

All of this suggests instead a repair job made to close a hole in the cladding: persons who were anything but sophisticated could have thus taken the first antique piece of marble that they had at their fingertips, which had been deemed suitable to be on a monument that was also ancient, regardless of what it depicted. What is called a ‘matching color patch’, in other words. The patch must have been made then when Roman marbles could still be found in the city, and since the scarsella is from the beginning of the thirteenth century, all of that would be dated to those years.

We don’t know what could have caused the gap: it could have even been an unintentional damage, given its location on the bottom, but I want to push myself to make a rather quirky hypothesis.

At that time, they were working on adapting the monument to its function as a baptistry of the city. In that context they had to set up a sacristy somewhere, and this was the small room that is there just on the back of our marble. Then in a sacristy it was important to have a water supply, and making it with a minimal impact of the plumbing. All of the connections to the city’s waterworks were on the west side, close to that angle of the sacristy: thus, they decided to pass some tubes through there, necessarily at the bottom. It was not an easy task, also because they had to avoid cutting or damaging the external plinth. The wall of the small sacristy was however – and it still is today – rather thin, and because of this, as always happens, it caved in; so, they needed to repair it immediately. And here we are.

Could that be the case?

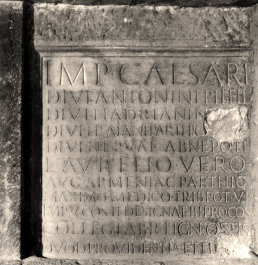

Yet I also have to say something about a marble slab with a beautiful inscription from the second half of the second century that is inside the baptistry, in the gallery. This marble measures approximately 1 square meter, and was used as a railing for one of the choirs. On it we read that it was made by the collegium fabri tignari of Ostia (a woodworker’s guild) in honor of the rulers of that time to whom – as can be understood by other similar inscriptions since this marble is partly broken – the guild expressed gratitude for some favor they had received (that’s to say, a profitable contract).

In the 1700s, this stone was believed to be proof of the barbarian origin of the monument by the scholars of the time. They explained that this was why so much “disdain” to use it as any kind of construction material was shown. In reality these scholars were very learned in theories but didn’t know much about construction practices because they didn’t consider the fact that on a building work always prizes doing what is most convenient if will get the same result. And thus, if there was marble available and that wasn’t of use to anyone, it could be easily employed where it was useful to do so, and this was not only done in the time of the Barbarians, obviously.

Therefore, having sorted out the scholars’ preliminary observation, we need to ask ourselves what such a so heavy thanksgiving message from a guild from Ostia was doing in Florence.

But Ostia was a very busy port, where certainly ships that brought marbles from the Aegean countries for the Temple of Mars would have stopped. Perhaps because of this, given that the collegium had existed no more from some centuries and that such a beautiful piece of smooth marble would surely be useful for making many things, someone took it, paid (perhaps) for it, and brought it off. Once it got to the worksite in Florence all they had to do was modify it a little, and here it was.

To make scholars argue.

From top to bottom: the bas-relief of a ship from the scarsella; detail of the floorplan of the ground floor of the Baptistry; the stone with an inscription from the second century enclosed in the railing of a choir in the gallery.