‘Se telefonando’…

I always enjoy listening to this old Mina song, also because I associate it with an adventure.

Not a few years ago, my friend R. asked me if I would help him take over a religious complex in a distant city in the Middle East, for a study that interested a local professor with whom he was in contact. We agreed, planned what we could and left loaded with various instruments. Since we both had school commitments, we agreed that the work would be done during the summer vacations: a month or so to spend in a place that was totally unknown to us. And I emphasize totally: the informations available, since there was no Internet, were in fact very scarce, but I remember very well the note that concluded the brief description provided by a Hachette guide: “For their own safety, Western visitors are advised not to approach the monument”.

Something worrying was on the horizon, but the die was cast and we left.

So, after hours of flying and a very long journey through picturesque but desolate places, on a rickety bus in close contact with a varied humanity, we arrived at the site and discovered that there was not a free hotel room in the entire city. Various instructive experiences followed, but in the end our very authoritative principals dislodged the legitimate occupants of a room in the city’s main hotel, and so we were able to settle in.

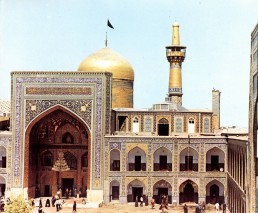

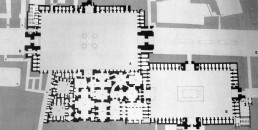

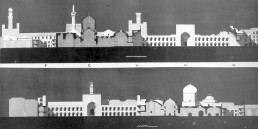

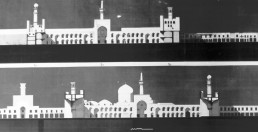

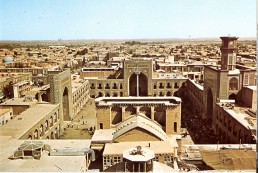

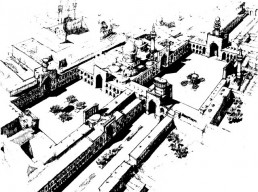

Although we had a special pass and could rely on the help of a young and willing engineer, it was soon evident that we had committed ourselves to something impossible. Not only was the place frequented by multitudes of people with whom, confirming the guide’s warning, it was inadvisable to relate to, given our evident extraneousness to the cults they practiced, but the monument itself proposed difficulties that we could not overcome. In fact, it was not a building, but an urban complex that occupied an area as large as 15 soccer fields, and even if we took away houses, stores, hospices, shelters, religious schools, markets and whatever else, there remained a monumental part that was more or less equivalent to four or five Pitti Palaces.

Let’s add that the terrifying heat, the suspicious overseers and the people animated by religious ardor that swarmed everywhere complicated even the simplest operations. For example: when we unrolled a metric tape to try a measure, the faithful would take possession of it and kiss it with devotion as if it had been an extra large rosary.

I believe that the face of the captain of the Titanic when he saw in the darkness of the night the glow of the fatal iceberg approaching, gradually assumed the same expression that formed on our sweaty faces when we became fully aware of the fact that whatever effort we had made, whatever subterfuge we had devised, the result could only be one: disaster.

In the darkness of despair, however, a faint and distant flame flickered: we still had a chance, albeit an unlikely one. The great and secular monument, like all self-respecting great and secular monuments, had at its service a legion of masons and decorators who provided uninterruptedly for its maintenance, and they reported to a technical office. Was it possible that in the technical office there was no relief?

As our iceberg, in the form of the month’s deadline, was approaching, we attempted a reckless move: to contact the chief engineer of the maintenance office to see if we could get some help from him. So we invited him to dinner and started telling him the usual stories about the beauties of Florence, the Brunelleschi’s dome and so on.

He was very kind: he didn’t know a damn thing about Florence, but he knew very well who we were and what we had come to do, and above all he immediately guessed where we wanted to go with all our chatters. And it was logical that he didn’t like the fact that his competences had been bypassed: we came in his domain to do things he was responsible for, without him having any say in the matter, nor any recognition or advantage. Unacceptable.

But the rules of good manners had to be respected, and he respected them by inviting us in turn to visit the monument. One fine morning he led us all over to see a lot of interesting things, but for us the most interesting of all had to be in his office: if any survey existed, it had to be there, and we couldn’t miss any possible opportunity.

So, when we returned from our tour and the engineer had us sit down in a small sober room that overlooked a wide cloister, as soon as we entered our eyes ran to scan everything for traces of reliefs, but on the walls there were only religious pictures and souvenir photos, on the shelves the folders of files and some books, and the desk was sadly empty.

So nothing, zero, the end.