The Meridian Doesn’t Work

The most beautiful doormat in the history of art is on the floor of the Baptistry, near the north door. It is a marble slab that has been trampled on for centuries without any thought, and which starting a few years ago – perhaps heeding some of my heartfelt recommendations – the Opera del Duomo has protected from walking on it.

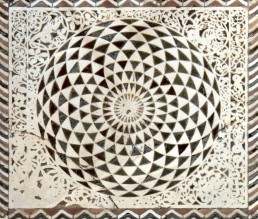

This marble slab represents the heavenly vault with the sun in the center, and around it the eight spheres of the Moon, the planets and the fixed stars. In a geometric sense, the image is a map, meaning the orthogonal projection of a hemisphere (the starry sky) on a horizontal plane (the earth), and it is absolutely extraordinary to see that this image was made by correctly applying the theoretical principles of projective geometry as described by G. Monge in the 18th century. The circles then are crossed by spirals formed by curved triangles shaped one by one, which create a hypnotic effect of rotational motion – a masterpiece of art and science.

To think that this image was created in the Romanesque period is obviously untenable, and so is attributing it to some unidentified Middle Eastern schools from that time. Therefore how did they conceive, in Late Antiquity and in the context of the construction of this building, this singular marble piece and accomplish it with such fine workmanship?

Here are a few traces that might lead us towards a possible explanation.

In order to celebrate the glory of the Emperor after his victory against Radagaisus, the architect of the Temple thought of some sun symbols. One took the highest beam from the annual path of the sun and projected it at noon on June 21st at a specific spot inside the building. This is what is related by the chronist Villani; but there is no trace of this projection on the floor by the north door, where the sunbeam would inevitably have to fall.

Near this spot there is rather the abovementioned marble slab, which carries obvious solar symbolisms. If this slab was created to receive the projection, why don’t we find it in the right place?

The answer: when the architect made the design he was far away, probably in Greece or in the Middle East, and he didn’t know the exact angulation that the solar beam would have had in Florence. He made some calculations anyway and he prepared the marble for the projection, with the foresight that it could be placed to measure on site. Thus, he created in the floor a rectangular panel with a design that allowed him to slide the marble in once he found the right adjustment. This was something which for whatever reason was not done: perhaps in the hurry of not waiting until June 21st the workers limited themselves to putting the marble in the center of the frame, with a simple decorative function.

These traces do not completely exhaust the mystery of our doormat, but perhaps they can help in further investigation.

Above: the solar marble near the north gate, the projected concept used to design its image and a few details that show the supreme quality of its workmanship.

Left: the solar projection inside the Baptistry at noon on the summer solstice, as it would have happened according to the story of Giovanni Villani, in a graphical reconstruction by the Museum of the History of Science in Florence.

The Rediscovered Column

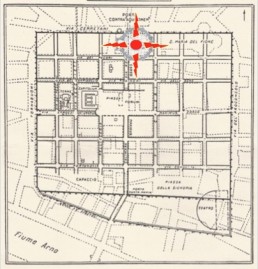

The column with the statue of Plenty today called Colonna dell’Abbondanza or formerly Colonna della Dovizia (Column of Abundance), which stands in the center of Florence, in Piazza della Repubblica, is the same one which at one time was at the center of the Baptistry and supported the dreaded ‘statue of Mars’ noted by Dante.

Here’s why.

A few of the very few who are familiar with my ideas about the origins of the Baptistry of San Giovanni – which is that it is not a Romanesque monument, but a Roman one, just according to the oldest Florentine legends – already know that one day, while I was looking at the Column of Abundance, it suddenly occurred to me that that column was the same one that had been placed in the center of the Baptistry to support on its capital the famous statue of Mars that is recorded by Dante in The Divine Comedy. Having done some follow-up investigation without finding elements contrary to my idea, I mentioned it in a brief publication on the origins of San Giovanni.[1] In my opinion, everything must have begun in 406, when at the slopes of Fiesole ended in a massacre the invasion of the king of the Goths, Radagaisus, who was defeated by the Roman army led by Stilicone. After that the Florentines, as Giovanni Villani writes [2], “commissioned to be done in the city a marvelous temple in honor of the god Mars” in memory of the event. And so, Florence got what after became its Baptistry. In those years between the end of the fourth and the beginning of the fifth century, the community of the city was marked by deep contrasts between Catholics, Aryans and pagans, given that each group sought to make its own claim. The Catholics, as soon as the construction of the Temple was finished, took immediate possession of it so they could make it into a church, and because of this they removed the statue and brought it to the Ponte Vecchio. The marble pieces of the shrine that surrounded it, instead, because of their worth, were dismantled and stored nearby, until in 1150 they were repurposed and modified to create the current lantern of the monument.

But also the column that supported the statue must have met a similar end, because I soon discovered that my idea about its connection to the column in Piazza della Repubblica was not new, as it had already been proposed in the 1500s. I will now attempt to summarize the question by availing myself of the information provided in by a fine essay by Margaret Haines.[3]

Today everyone agrees that the column is Roman, and it is certain that in 1429 it was lying since time immemorial at the foot of Giotto’s belltower. Then, in that year, the Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore granted it, in exchange with some warehouses existing in the Old Market, to the Officers of the Tower, meaning the proposed legal authorities for the management of the city’s public spaces, who intended to use it for what would today be called a street furniture intervention which planned to place it in the Market and put a statue on top of it that would represent Plenty, which Donatello had already been commissioned to carry out. But Donatello was famous for his sluggishness, hence it was only after several reminders that he delivered the statue in 1430, and so the plan could be completed. The expectations of the commissioners despite of the delays, mean that the column and the statue were part of a single project just from the beginning, a project which foresaw a significant expense because the transaction was done in exchange for some warehouses, and also because such a beautiful column was very valuable and because they had hired the best sculptor.[4]

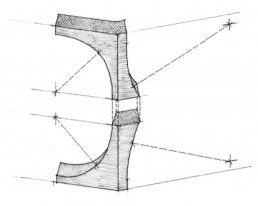

At this point we must embark on another topic regarding what the relationship of the column with the Baptistry is. This column (let’s call it ‘Column A’) is clearly similar in proportions and material (granite, probably from Elba island) with the other twelve columns (‘B’) of the bottom interior order of San Giovanni, but it has a height lower about 25 cm in comparison to them. According to ancient tales, this column ‘A’ was originally placed just to the left when you enter from the Gates of Paradise; from there it would have been removed and substituted with the fluted column there now (‘C’), which is made with white marble like the other ‘C’ that’s on the right when you enter. And here we have a confused mix of coincidences: the ‘C Columns’ have the same size and proportions as the ‘B’ but different materials, while the ‘A’ is in the same material but does not have the same height. According to the legends, and endorsed by various authors in the 1500s (Albertini, Borghini, Vasari), ‘Column A’ would have been just the one that supported the statue of Mars in the center of the Temple and that was removed by the Christian Florentines.[5] Today scholars, however, although they don’t object to the fact that the ‘C Columns’ are antique and placed in San Giovanni in the Christian period, when it comes to explaining why they are different from the B Columns, they say they are sourced from lost monuments from Roman Florence or its vicinities.

But this claim doesn’t hold water. It is, in fact, impossible to believe that some recovered columns could have been inserted with such exact measures and harmonious proportions, despite the difference of the material, in a highly calibrated formal context like that of San Giovanni; and moreover, in Florence or its outskirts no traces have ever been found of some Roman building that could have had similar columns, not even in the city Capitol. Even more incredible is the idea that these columns could have substituted previous ones, because there was no reason to make a transformation clearly detrimental from an aesthetic perspective and that would have posed a great risk to the stability of the dome, and of which – what is more – no traces in the walls were found, which instead would have inevitably happen. [6] Some other observations could be made, but let’s stop here and try a logical explanation, that there is. We can derive it precisely from the Florentine legends, which under a cloak of fancies hide some elements of truth.

Thus, here’s how the events could have unfolded.

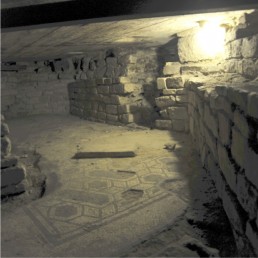

Originally Column A and the statue of Mars were at the center of the Temple. Both were removed when the Temple became a church, because they obstructed the space and also because the statue seemed a pagan symbol. But it is important to add a detail that isn’t considered by scholars, which is that the statue was not only a symbol of victory, but also a symbol of peace and prosperity: this was documented very clearly by some finds in excavations in the 1800s, which documented the rituals of the Temple foundation but were not recognized by the archeologists at the time. It’s hard to believe, but it is true, and it’s even more incredible that since then no one has done any check investigation on the excavations reports of the time or about the remains that are still visible under the Baptistry.

The statue was not only a symbol of war (Mars, who anyway was the Emperor himself in the guise of a warrior) but also the wish of a better future for the people after their narrow escape from danger, and all these concepts were certainly ingrained in the memories of the people and the intellectuals up in the Renaissance even, and it is just this that Leonardo Bruni thought about when he laid out the plan to redevelop the old market. Margaret Haines sensed this when she wrote that the plan “in all probability understood from its inception the idea of the allegorical figure of Plenty, almost as a virtue personified by the goddess, but also as a vow of prosperity in times of hardship for the Republic.” [7] Its connection with the classical world thus was there, and not only for cultural reasons or artistic aspirations: rather it was also there to reconnect the Florentines to an ancient and powerful augury, for which they appealed to Donatello to make an embodiment of; and this indicates how much certain beliefs were alive and pervasive throughout Florentine society.

If we follow this traces, at last other knots of the question are unraveled. One regards the similarity of Column A with the B and its difference in height, that are explained from the perspective of composition and image. For various reasons which I exposed in one of my previous studies,[8] the image originally offered by the Temple inside was very different than what does now. In the center, around the statue of Mars, there was a shrine similar to the one painted by Vasari in the ceiling of the Salone dei Cinquecento (Hall of the Five-Hundred) in Palazzo Vecchio, and the Column A inside it was clearly similar to the B Columns, but a little shorter since it had to stay on a pedestal and support the statue. Because of this its height was calculated so it wouldn’t be disproportional or stick out above the trabeated circle of the shrine too much. That also explains its identical proportions and materials with the B Columns. Why the C Columns are different remains to be cleared up, but there is an explanation even for this. These two columns have always been where they are now, and they had to be different from the others for symbolic reasons, that we understand observing that even outside next to the East door there are two different white columns from those of the North and South doors, which are dark green. It comes down to a kind of solar symbolism frequent in Antiquity and related to the cult of the victorious emperor, whose power was compared to the sun who every dawn defeats the darkness. It is for this reason that every morning the sun’s rays had to enter from the East door and illuminate the statue: a celebrative symbol, therefore, that can be added to the other similar symbols present throughout the structure. [9]

The fact that later the column of the Old Market, in 1429, was found to be owned by the Opera di S. Maria del Fiore and not the Opera di San Giovanni, as it would have been logical if the column had originally come from the Baptistry, can be explained by the fact that, since it had laid abandoned for centuries at the foot of the Belltower, it must have been peaceably considered property of the Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore, all memory of its origins having been lost. A form of adverse possession, in short.

Lastly, it is needless to further investigate the idea that our ‘Column A’ was a piece recovered from Santa Reparata, a cathedral that was ugly and graceless according to the Florentines at the time, and in which remains there have never been found anything that would suggest it was dignified with such precious frames.

And with regards to the fact that the column was placed by grafting it with a solid iron stud in the stump of another older column, now disappeared underground, but which in 1429 still stuck out of the soil at the intersection of the two main roads of the city, this confirms a clear desire to be traced back to the Roman origins of Florence, which were seen as a source of city pride. [10]

So we can be certain that the column that was in the center of the Baptistry, when, as the oldest legends relate, was a Temple of Mars is precisely the one that today stands in Piazza della Repubblica, to support not only the weight of its statue, but also that of centuries of history.

Note: quotes from the texts of M. Haines are freely translated.

[1] Degl’Innocenti P. (2019) Il Battistero di San Giovanni, un enigma fiorentino – Studi, leggende e verità da Dante a Ken Follett, Firenze, Pontecorboli.

[2] Nuova cronica, I, XLII.

[3] Haines M. (1984), La colonna della Dovizia di Donatello, Rivista d’Arte, year XXXVII series IV, vol. I, pgs. 347-359.

[4] Haines M. (1984), pg. 348.

[5] Haines M. (1984), pg. 354 footnote 22.

[6] Degl’Innocenti P. (2017), L’architettura del battistero fiorentino di San Giovanni – Progetto, appalto, costruzione, vicende, Firenze, Pontecorboli, pg. 85 f.

[7] Haines M. (1984), pg. 356.

[8] Degl’Innocenti P. (2017), pg. 89 ff.

[9] Degl’Innocenti P. (2017), pg. 81 ff.

[10] Haines M. (1984), pg. 355 footnote 25.

The columns have always been of great value, because of which, if they were not used, would still have been kept. This is the column of Piazza Santa Felicita, which had a similar fate to the one in Piazza della Repubblica: having made a narrow escape from the destruction of 1944, it was stored for many years in a nearby courtyard, until it was returned to its place.

Recycling a Monument

The construction of the Temple of Mars must have been promoted by Stilicho soon after his victory against Radagaisus: let’s say around October-November of 406, while its conclusion is indicated by a mission of Florentines who went to ask Emperor Honorius permission to remove his statue, mission which can be posed no later than August of 423, the date of his death.

Thus in 423 the statue was in its place, and the Florentine Christians wanted to use the Temple as a church: this means that at least the rough construction was completed, and in the interior flooring and claddings were also done. Therefore, the construction lasted 17 years, to which a few years can be added because they still had to carry out the external claddings, or, if not all, then at least a part of them, given that the marbles of the corner pillars were posed only in 13th century. In total, thus, we can calculate little more than twenty years for the construction, which is a possible but rather short timeframe, because in the calculations not only should the duration of the work be understood, but also the time necessary for the preliminary agreements to be made, the design to be drawn up, the search for the architect to head the project, as well as the stipulations of the contract should be factored in.

If these preliminary phases were short, it means that the channels activated in Rome, and which are spoken about in the chronicles, worked to perfection, and if the building proceeded speedily regardless of the distance from which the worked marbles arrived, we can deduce a great organization of the contractors. Fruit of centuries of experience, that organization allowed them to restrict the timeframe and optimize the chain of production, transportation and assembly of the marbles, and work in Florence on the rough walls while at the quarries (which I believe were in the Aegean region, between Greece and Turkey) they prepared the marbles.

But the design had to precede the work, not overlapping on it, and for the drafting of such a perfect and detailed design three to four years could be estimated, which should be taken out of the calculated twenty, and so it would critically be constricted the building timeframe.

And then?

Then there are two hypotheses, not necessarily alternative, and both plausible and consistent with the historical context.

One is that we are facing an entrepreneurial feat made necessary by the disastrous situation of the public contracts: a construction company couldn’t miss this kind of opportunity, so every record was broken.

The other, is that the Florentines bought a pre-made package of design and marbles; and this would be a rather fascinating case, but with a good probability of being well-founded.

Could someone have needed a similar monument earlier and then not begun the commission?

Yes, it is possible and actually probable: the same Stilicho four years earlier celebrated another great victory of his when he pushed back Alaric’s barbarians in Pollenzo in 402 and erected a triumphal arch in Rome. Here we would need to open up a parenthesis on the personal events of Stilicho in those years, but let’s only say that he had a lot of enemies in the Senate that wanted him dead; and in fact, in 408 he was killed in a plot that did not spare his son, his wife, his friends, his proteges, his soldiers. A damnatio memoriae followed [that’s to say the total erasure of all memory of a person’s existence], because of which we don’t know much about his triumphs, but some traces on the subject remain. It is therefore possible that some initiative of his was left halfway done, and that he brought it to completion on this other occasion and shortly after the former, thanks to the Florentines.

One final observation should be made regarding the date of 436 as the completion of the construction that the old historian Filippo Buonarroti records having found written it in a note now lost. This date would add another dozen years to the calculations we made: how can we explain it?

An explanation could be that the note may have been referring to the completion of the work of transforming the building into a church, and it is also imaginable that the Florentine Catholics would have lost some time in gathering the funds necessary to make the transformations by using a kind of crowdfunding, given that there was no hope of any public financing.

Thus, in conclusion, it would not be a coincidence if the architecture of our baptistry had such absolute and ideal shapes, because in all likelihood it was designed to be placed in whatever space there was available to celebrate the glory of Rome. Here in Florence, it only needed a few adjustments – about which I believe there remain a few traces – and everything would fit into place.

And it would come as no surprise that the solar meridian didn’t work: according to very recent studies by Gabriele Casetta, in fact, it would have been calculated on the basis of the inclination of the solstitial sunbeams precisely at the latitude of Rome [1]. [1].

[1] G. Casetta, “The Baptistry of Florence – A Liturgical and Symbolic Reading” – thesis defended at the Pontificio Ateneo Sant’Anselmo in Rome a.a. 2021, p. 128 (unpublished).

The source areas of the marbles of the Baptistry.

Vultures in the Gallery

As is the case throughout the entirety of the Baptistry, it is not even known when the unusual paintings that decorate the walls of the gallery were painted, or by whom.

According to today’s scholars they must be Romanesque, given that they are on what according to them are Romanesque walls. However, it is permissible to harbor some doubts about this opinion, especially since these paintings do not represent religious subjects, but secular ones: only animals and geometric patterns, all strictly in black and white – an artistic heresy for a Romanesque Christian building. It would be little wonder if after the first brushstrokes the painter had been immediately fired and severely punished. Instead, he was not only allowed to continue his work without being thrown out on the spot, but went on to decorate all of the walls. Yet a short time later those black and white paintings began to be covered by brightly colored mosaics of “religiously correct” saints and prophets.

Does all of this seem reasonable? I don’t think so.

But if, on the contrary, the walls were not Romanesque, a completely different history could be related. Here it is.

The Baptistry was built as a ‘Temple of Mars’ in the fifth century and cost an exorbitance. Towards the end of the work even the prosperous settlers of Florentia ended up in the red. In order to finish the interior on a budget, instead of marble panels they thought to use paintings that from afar could appear to be black and white marble as the rest. At that time skilled painters were very few and expensive on the payroll. Therefore, since the enterprise was running low on funds and the deadline was tight, they took on a few good-willed youngsters so that they could undertake to draw up something decent under the guidance of an expert master.

The master took it upon himself to encourage the imagination of his ragtag band of guys. But if he suggested to paint a bird showing a nice raptor, the apprentices didn’t get beyond a few little ducklings, and if he laid out an elegant composition of geometric racemes, he was merely met with some wonky curlicues. All of this was frustrating, but that was the skill level of the first Florentine painters: practically nil. There was no Cimabue on the horizon yet.

The vultures that can be seen in a tribune of the north west gallery tell us where the talented painters came from. Apparently, these birds must have been painted from memory because it is rather improbable that they had captured them in the nearby hills or that they would stay caged in order to be used as models: these were vultures from the mountains of the Middle East where the painters hailed from. Middle Eastern like the marble workers, the enterprise, and the architect.

3- The Temple Didn't Wear Prada

(continued)

11 – The Project is a Person

At this point a question bore asking: how were they able to manage such a complex construction at a work with multiple locations? The answer would require a very long discussion, but let’s look at some of the fundamental points briefly.

For the contractors it was naturally a vital precondition to the whole work that a very well-defined design should be drafted that did not entail corrections, doubts, or second thoughts, or it kept them to a minimum, otherwise, given the distances that they had to cover, the entire endeavor would have been a failure. And the Baptistry testifies fully to the fact that this is the course that was taken, because it is such a perfect mechanism that it prompts the unconditional admiration of all of the greatest architects of all ages. The design of the Temple did not allow for modifications.

But this design, materially speaking, how was it made?

Obviously, in the ancient world today’s representation systems of technical drawing did not exist, but they knew how to draw floorplans, sectionals, detailed drawings, and they used models, templates, and samples. All of these partial representations together however had to find those who knew how to manage them, and that was the architect. Thus, at the time a draft was not a collection of documents, i.e. illustrated tables and written pages, as it is today. Rather, it was a person, the architect himself, who knew how to utilize the drawings and models that were needed, and he imparted working instructions to those who had to carry out the task. Like a conductor who knows the musical score by heart, he had to have all of the individual operations that were needed to construct the building clear in his mind. He was also ready to explain them to the master builders and to the workers and to find solutions to their problems in order to successfully finish construction according to the established terms of the contract.

The architect was qualified to do so not only on account of his personal skills and his studies, but also because he had undergone a proper apprenticeship with a group of builders or an enterprise. And with regards to the latter, it is believed that the builder of the Temple was of Greek or Middle Eastern origin, given that the greatest centers for the processing of marble for monuments were in the Ionian area, and that he may have moved to Florence in order to monitor the work along with a group of colleagues who had to maintain the relationship between the ones carrying out the work and the material suppliers. Besides this role of supervising and coordination, he was given the task of maintaining relations with those who had commissioned the building, whom he had to answer to about the progress of the work.

12 – The Temple Didn’t Wear Prada

The role of a Roman architect was quite different than what is understood today; or at least, I do not dare to think what would have happened if to construct the Temple the duumviri of Florentia had turned to, as our mayors do, a bigshot starchitect, if at the time there were any. The starchitect would certainly have demonstrated his imagination and his tastes by creating a griffe-masterpiece, made in his image and likeness, that is, according to his personal brand. Thus, today we would have had the Prada or Armani Temple, which is to say a great architectural firm, whose fashion house would have born a recognizable and indelible impression.

Lucky for us and for Florence, for art history and the history of architecture, things did not happen that way. The Temple could not bear the distinctive signs of a singular figure because it had to represent Rome, its history, its culture, its people. It had to be a choral monument: the architect had to have the liberty to express himself as an engineer and as an artist, but also stay within a rigid frame of which symbols to use and which messages to convey.

The form had thus very precise rationales, and it is not an exaggeration to say that it was thrilling to find them brought to light not only in the customary precious texts of Classical Archeology, but also in Roman religious texts. This should not be surprising because in the Roman world the natural and the supernatural coexisted in a perfect overlap, which we moderns find difficult to imagine flowing into the thousands of streams of daily existence, because for us the supernatural is restricted to very limited areas of our lives, or no longer falls within them.

I had another interpretation of the monument that was added to the preceding ones: about the project design.

13 – At the Teachers’ Exam

And so, I had found another key to understanding the monument, that of the design, and as a professor of design I couldn’t for one second resist the temptation to imagine how the architect’s exam would have gone.

Here is the result of the imagined-exam.

1st Topic: Celebrate the Glory of Rome

The candidate demonstrates adequate knowledge of the Triumphal Art by proposing a composition based on a central space with a shrine and a trophy. The symbols are expressed with appropriate emphasis and appear to be understandable even to someone who is illiterate. The interpretation in a metahistorical key of the internal space is commendable. The heroic symbols placed on the rosettes of some of the columns are unoriginal.

Rating: Fair.

2nd Topic: Celebrate the Victorious Commander

The candidate proposes to portray the emperor with an equestrian statue placed on a column at the center of the shrine: the composition is correct but not particularly original.

Rating: Satisfactory.

3rd Topic: Design the Hearing Place

The candidate proposes to lay on the floor a red porphyry disc, a normal rota porfiretica, but he enhanced it with a rather original design that visualizes the distance to be kept from the sacred person of the sovereign very well.

Rating: Good

4th Topic: Design the Apparatuses for the Cult of the Emperor

The candidate proposes creating two symbolic events focusing on the projection of sun’s rays in the interior. One consists in capturing, at noon on the summer solstice, the maximum power of the star thanks to a special meridian to be aligned towards the northern door. The other regards the celebration of the victory of the Sun every morning at dawn against the darkness of the night by making the first day’s sunbeams pass through the eastern door.

The committee observes that the proposals are not particularly original because they fall within the prevailing traditions. The installation of a northern meridian seems to be very problematic while the symbolic role of the east door should be highlighted with some elements that emphasize it.

Rating: Rather abstruse, but original: Good.

5th Topic: Ideas for an Augury of Prosperity and Peace

The candidate proposes to not modify the integrity of the space of the Temple with inappropriate additions, but rather to create, for the occasion of the inaugural ceremony, a temporary apparatus centered on the symbols of the god Terminus. These are suitable to express the concept of the hoped-for resistance of the empire in the face of future invasions in a manner that is comprehensible to all.

Rating: Satisfactory.

The candidate is approved with a grade of 28/30.

(followed by the date and illegible signatures)

Not the most brilliant score, as one can tell, but those professors with little open-mindedness (they exist, you know?) made their assessments by basing everything on the tunnel-vision of formal art, and probably they were also a tad envious of the prowess of the candidate. It happens.

It’s just as well however that they didn’t reject the idea of Terminus: without Terminus the present study could not have begun.

14 – A Sequel with a Happy Ending, but…

Having passed the test, was it the research over? No: another one started about the second life of the monument. A sequel.

Setting: a prosperous small town, salt of the earth people, dedicated to the work.

Plot: the construction of a new look that renders the protagonist, a former Temple of Mars, presentable. But presentable for whom?

Let’s have a look (in order of appearance).

For the Catholics? Impatient, they make it their own right away, but they are soon kicked out.

For the Aryans? They take it over by making use of political protections, but they don’t last because a war breaks out.

For the Byzantines? They occupy the city in the midst of fierce engagements with the Goths: they have other things to think about.

For the Goths? On account of superstition, they avoid Florence remembering of how badly it went for Radagaisus.

For the Florentines? After the war they have eyes only for weeping and they are tyrannized by the people of Fiesole.

For the Lombards? Tough guys, imagine that.

For the Franks? Occupying forces.

For the bishop? Gone for centuries.

So, for who then?

The protagonist, our Temple, is a foundling worthy of a Dickensian novel by now. No one is willing to claim ownership and rights, those who have power in the city would want it for themselves because it’s beautiful and gives prestige, but they don’t spend a cent to maintain it. They don’t even know what to call it, because it’s not a Baptistry, or what do to with it exactly: its religious use is not exclusive, a little bit of everything is done there, there is a great deal of confusion.

The sequel is boring, nothing happens, its viewership crashes. It needs someone that can really boost its ratings. And at last, here he is: someone powerful, cultured, and who loves Florence. It’s the Pope, what more could you want? And Pope Nicholas takes action: he decides on the exclusive use of the baptistry, he finds sponsors who have the money, and he launches a works and decorations program. Long live Pope Nicholas.

Everything’s nice and clear. Except for one thing: if the Temple officially becomes the baptistry of the city, the small and clumsy Santa Reparata cannot put itself forward as its cathedral. As long as their roles are different, it’s okay: otherwise, the contrast is merciless and Florence makes a ridiculous impression to those who come through on their way to Rome, to say nothing of a comparison with Pisa. However, the decision is made. Even if they will have to construct a more beautiful and greater cathedral, and even if this will mean an enormous expense, the Temple of Mars becomes the Baptistry of San Giovanni.

Thus, the work begins, but without realizing that the new cathedral would have to have a dome the likes of which had never been seen, and this could have meant disaster.

But luckily, we know how things went in that.

15 – At the End of the Movie

So, what at the beginning seemed like a silent movie had finally found its soundtrack. We got a complete explanation even for what appeared inexplicable, or what many had tried to explain in every possible way, even with mental contortions very close to the absurdity. Moreover, the legend of Mars was also explained, a legend born in tragic circumstances and that had the Temple at its center. It is on account of these that we can explain the deep love of the Florentines, who saw in their Temple-Baptistry the testimonial to their misfortunes.

The achieved results opened to many possible research pathways, and it was depressing to think how the insistent idea of a medieval monument has been a waste of time for those who study art and history, who teach, and who love Florence.

We discovered that in the heart of Florence there is a building that is the only one of its type to reach us intact and which could be studied in a new and broader perspective, even considering that, since the three-quarters of what lies beneath its floor still remains to be excavated, many other intact and very interesting finds can surely be find out, as burnt remains of fruits and harvests that could speak about the cultivation practices of the time, or samples of mortars that could be submitted for radiocarbon dating and compared to those from the upper walls. There are many research questions that could be asked, and with better expectations than those for example that were had when they went to find the remains of Monna Lisa in the lost church of Sant’Orsola.

I thought this stimulating scenery of new researches could interest those who study the topic, but I was wrong. Officially the Baptistry remains Romanesque: a history that does not hold water continues to be believed in.

But can we mean that it has turned out to be a remarkable tall tale? By now, how can we trust in those who say that the baptistry is Romanesque if they, to prove it, need to rewrite the history of art anticipating by few centuries the Renaissance? This upending all the criteria used and shared thus far seems like wanting to maintain that the sea came into being because of the fish, and not vice versa.

In the end, as we have seen, the chronicles can explain everything in a way that isn’t contradictory. Following them one can get to the top of the Baptistry: it is a hard climb, but from up there we can see a most beautiful panorama. All those who believe that the building is Romanesque don’t know what they’re missing.

2 - Chatters from Behind the Fences

(continued)

6 – They Were not Barbarian Stormtroopers

All of that made sense. Therefore, was I on the right track? Yes – actually no: I still had to answer the question of the remains of the Roman houses. I went again to bother my caretaker friends, to reread the reports on the excavations, to look with a magnifying glass at the photos of the findings, and in the end my eyes opened. I ran to the basement of the Baptistry to check, and it was just so: no destructive fury of barbarian Stormtroopers, the houses hadn’t been destroyed but meticulously demolished. The same result, but with a fundamental difference.

Could it be possible? This meant in fact that the Temple had been constructed on a built-up area, while the houses were still erect and lived in, and they had been demolished to create a space for it. Another mystery to solve, and if I didn’t, all of my hypotheses would fall like a proverbial house of cards.

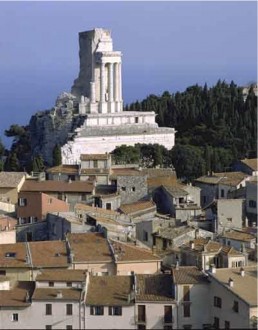

Consequently, I anxiously resumed browsing archeology texts, and in them once again I found the solution. A trophy should be placed such that it faces any incoming danger: in Florence, therefore, it should lie close to the northern walls, in the direction of the mountain passes leading towards Mugello valley, where Radagaisus had come from and where new enemies could still appear. And not only that: the trophy had to be made within the city walls, so as not to create a useful stronghold for a besieging force, and yet be as close as possible to the Northern gate because just outside of it the Mugnone creek flowed, which was the water way used to bring in loads and marble that had sailed up the river Arno.

So that all was straightened out.

But could the city officials truly impose such a choice? Here the research branched out to topics that regarded the ownership of the soil of the Roman colonies and of that area in particular, and the urban layout of Florence at that time, but I found elements of consistency among these subjects also. Everything fell within the perspective of an exceptional intervention, one of those that today are called ‘supreme emergency’, and are implemented in extraordinary circumstances. This was also demonstrated by the fact that that section of the wall showed signs of a work done in haste.

7 – Terrible but Human

By this point I seemed to have arrived at the clarity I had been looking for on the matter. The Baptistry could be considered a fully classical monument, and the theory of its Medieval origin could be thrown in the trash bin with the support of its pivotal argument reduced to crumbs. Entire libraries could be tossed out.

Obviously, that didn’t happen. Those in the past were not, but today’s scholars are all in favor of the Medieval timeframe, and my ideas have certainly not troubled their sleep. Nonetheless, it was important to me to see where my research would take me, and that which was emerging was a convincing, linear explanation, and – a very important issue – entirely in agreement with the historical chronicles. Once the embellishments and works of the imagination that are inevitable in stories that have been passed down orally from generation to generation have been taken out, it turned out that essentially the Florentines were not telling tall tales.

Everything all set, then? Not at all. Terminus, the immobile and silent figure who had started it all was still waiting for an answer. In this setting, what part did he have to play?

He had a part to play for sure, because Terminus, the ultimate symbol of stability and stillness for any Roman, was at the center of the wholehearted, touching message of auspice and hope that the monument had been entrusted to deliver to eternity. Thus, the Temple was not only a war memorial and a threating and powerful symbol, but also the depository of a choral and deeply felt augury for the fate of the people, the city, and the empire. And this ‘human’ aspect of the terrible tropaic monument explains the Florentines’ strong connection with it, which went beyond that of art and beauty, because the citizens remembered that within that monument a little flame of hope was lit that would not be extinguished, no matter what. But before I can explain all of that I have to open a short parenthesis about what happened in Florence in the days of Radagaisus. I warn you that I will use a dash of imagination, but the essence of the story is provided by reliable historical references.

8 – Martian Chronicles

When the King of the goths came south from Mugello valley leading an enormous horde and preceded by a well-deserved reputation for cruelty, Florence must have been laid low with hysteria. A few more days and the city would be overrun, houses would be ravaged, and the inhabitants either killed or taken as slaves. A nightmare. Instead, general Stilicho arrived at the last moment leading troops from as far away as Gaul and everything was settled in an ending that anticipated that of the movie ‘Stagecoach’ by fourteen centuries. It seemed miraculous, and actually they truly believed it was a miracle: prayers and thanksgiving of every kind rose to the heavens – while on earth they lashed out at the prisoners.

Stilicho also had very earthly concerns. His enemies were plotting against him in the Senate by influencing Emperor Honorius, and so he thought to flatter the soft young man by crediting him with the victory in a grand celebration. In this way he would also motivate the army, which was composed of disparate and ragtag troops (many of Radagaisus’ own soldiers took the opportunity to enlist), troops who needed to believe in the great destiny of Rome not so much for high ideals as much as for the hope of loot and plunder. In this way, Stilicho filled the pockets of his soldiers right away by selling thousands of prisoners into slavery and promoted a triumphant celebration leading the troops through the city where he had put up in a hurry a triumphal arch. Then he proposed to the Florentines that they erect a majestic monument, and quickly, as if he had premonitions of the sorry end that he would meet two years later. The idea found immediate consensus (and who could object?), also because the city was a settlement of former soldiers and certain traditions must have still been very much alive.

The chronicles relate that he contacted the greatest builders of the empire through the senators of Rome, and that is in accordance with the times, besides being perfectly logical. One had to trust those who knew how to do these things, and there were people in Rome who had contacts throughout the political sphere and that of important building contracts. Florentines were directed to them by the same Stilichoe (or perhaps by his wife Serena, who was well-connected: who knows?) and they asked for the most beautiful structure that could be made and guaranteed to cover the expense. Because here was the weak spot in the whole enterprise: money. Stilicone did not have it, and Honorius didn’t either. The Florentines on the other hand mustn’t have been doing badly, and thus, bleary-eyed with enthusiasm, they underwrote a substantial contract. It was a real godsend for builders in a time of total crisis in public contracts, but it was a trap for the inexperienced settlers.

There were all of these preconditions for a building scheme on a grand scale, in which everyone had a part to play, including the emperor who was unperturbed by the conflict of interests in supplying marble from the quarries he owned. And the Florentines, who had agreed to pay, paid dearly for it.

Ultimately the structure was truly the most beautiful that one could wish for, but very costly. By observing with the eye of a worksite surveyor the sequence of the improvements that were made, one can understand very well that the later ones were torn down, and that means that things were going badly financially. All of the estimates had been exceeded and now the coffers of the city were practically empty. But with a bit of good will they managed to bring the Temple to completion: it would take about twenty years, and we can go ahead and compare that timeframe to today’s.

9 – Chatters from Behind the Fences

Given that the surveyor’s gaze looked like it would work perfectly for me, I thought I would use it in order to extend my inquiry into the very straightforward issues of the worksite and the contract. This was an endeavor that could be undertaken because the monument is largely intact, the fruit of a unified project with few and minor modifications. Thus, I thought to cross-reference information from the analysis of the structure, the finds of the excavations and a few hints of the chronicles (hints that surely echo the chatter from behind the fences of the sidewalk retirees who passed the time by criticizing what the builders were doing) with the provisions of the contract and the worksite procedures, which are, broadly speaking, the same as those of today, as the ancient clocks measured time with the same criteria as modern ones do.

Thus, like a carpenter who thinks about the kind of hammer he’ll use to drive a nail in as well as the kind of wood where it will be stuck into, I tried to place each fact in the working context it could be connected to and test it for consistency. It was comforting to observe that the result indicated a coherent picture. Finally, the walls began to speak, and in order to listen to them it was enough to tune oneself in to the wavelength indicated by the surveyor: the series of procedures that are done in order to build.

First there was the contract: and from historical events, as we have seen, one could broadly infer how things went.

Then there was the building company aspect: it was certainly a massive undertaking given the time restrictions and the complexity of the work organization, and it proved itself to be very well set up, and not just for making beautiful things, but for being able to manage a contract long distance, in multiple locations, and coordinate timeframe, transportation, supplies, production, designs, workforce, payments.

At the heart of the entire operation was the design, which functionally had to be drafted in harmony not only with those commissioning it, given their power and their particular needs, but also with the business side of things, because it was based on the draft that supplies, production, and transportation needed to be organized. The design was therefore not just a masterpiece of aesthetics, but also of proficiency.

In short: the Baptistry-Temple mustn’t be seen solely as a masterpiece of architecture, but also as one of the entrepreneurial and organizational capabilities of a grand undertaking from the ancient world.

It was for this reason that I was very cautious when someone would let me know about the results of a new examination from samples taken with some sophisticated instruments: it only revealed the naive enthusiasm of those who think that one single data-point could possibly resolve such a complex problem. A similar methodological strategy is to be avoided absolutely, and if one happens to come across it, one must think it was due to simpleness, ignorance, or bad faith.

10 – With the Surveyor’s Gaze

So, putting aside the aesthetic and artistic assessments, I fell into the role of the worksite surveyor once again, and I tried to reflect on the task that the architect had had to face as the responsible for such a challenging work. It was logical to think that he had taken into account the fixed obligations of the procurement contract as he made his choices. Bearing this in mind, I found the fact that he had employed Grecian marble significant. It was a choice that didn’t seem to be made on account of aesthetic considerations because similar pieces of marble could also be found in Tuscany, but rather due to factors of operational expedience, such as those of cost and the reliability of trusted suppliers.

This confirmed that it was a contract that was managed far away from Florence, by contractors who were able to handle large orders of worked marble, transfer materials and labor, to organize, to inspect, and to provide accounting for. All of that was consistent with what had been related in the chronicles: “They sent a mission to the Senate in Rome and asked that they send them the most expert master builders that were in Rome.”

Even archeology texts confirmed that my hypotheses held water, but when I went to verify them with what the monument revealed in reality, more questions steadily emerged. Had the claddings been completely worked at the quarry or were some parts also done in Florence? And did the workforce also come from far away or was it partly local?

Some clues seemed to suggest a collaboration among expert workers from outside the city with local workers, who were lower level and guided by the more expert ones. And such a good architect could not have not taken these conditions into account when he was drafting his design. Perhaps the extensive use of geometric designs in the cladding could have been considered the most suitable for practical reasons, given the difficulty of assembling them long-distance.

Furthermore, some details of the cladding reveal an accuracy and refinement that could only be explained by the work of very skilled hands under the direct control of expert eyes. The enterprise must have relied on trusted laborers for such delicate work, as on the other hand it was logically expected in such a context. Many workers must have remained in Florence for a long time, actually for forever if one thinks about that suburb by ancient origins, which would one day be named “of the Greeks.”

(continued)

The Temple of Mars as a magical sentinel to defend the city.

Basements with Roman finds.

The Roman god Terminus.

Ivory portraits of Stilicho (left) and emperor Honorius.

The probable quarries of the marbles of the Baptistery.

Can it be believed that it was a Roman decorator who crafted this small masterpiece of geometry?

1 - Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde

Premise

The following articles concern my research on the Florentine Baptistry. It is a complicated topic, and I relate here what I have to say about it. I do not claim to have it all figured out, and I have probably run into some mistakes: bear with me.

In any event, I think I am right in essence for the simple reason that my thesis is in agreement with the historical chronicles of ancient Florence: because it is not obvious why the Florentines would tell tall tales, even if they mixed fanciful elements into their stories.

Please excuse me also if you find some explanations or some criticisms of others’ theses a little pedantic, but for those who are not familiar with the topic I have to give some background information.

A synthesis of my research on the baptistery can be found in the little book “The Baptistery of San Giovanni, a Florentine Enigma. Studies, Legends and Evidences from Dante to Ken Follett” (Pontecorboli ed., 2019, p. 88), cited in the page ‘Scritti’ of this site.

1 – How I Fell into a Black Hole

Everyone is familiar with the Baptistry of Florence, the beautiful San Giovanni loved so much by Dante, and it is obvious to all that the baptistry is a masterpiece of Florentine architecture. In my opinion none of that is true: it is not a baptistry nor a Florentine handiwork, and those who would like to know why can read what I’ve written on the subject. Here instead I relate how I came to such a bizarre conclusion: a long journey often marked by chance.

It all began many years ago, when, during the discussion of a thesis in Architecture, Prof. G., the president of the committee, interrupted the candidate who mentioned venturing into the topic of the origins of the Baptistry: “Look, forget about it, this is a problem that quickens the pulse.” The poor soul made a quick about-face, and he did manage to graduate, but that rough brush-off by Prof. G. made me pause and reflect. So – I thought – in the center of Florence, and at the heart of its history and art, there is a very deep black hole, in which who knows how many explorers have been lost.

I certainly couldn’t have imagined that I would find myself becoming one of them, but it happened like that.

One afternoon while I was on a street in the city center that I don’t usually walk down, I discovered a second-hand bookstore that had in the corner of its window display a little yellowed booklet that sparked my curiosity: Terminus – The Boundary Markers in the Roman Religion. This is how I made the acquaintance of this very strange god – Terminus indeed was a god – whose function was to stay planted in the earth and to do absolutely nothing. Explaining why the Ancient Romans, a people with common sense, had conceived of such an anomalous divinity would be a discussion that holds many surprises, but also one that would take us far from the point. Here it is sufficient to say that, as I would soon discover, the key to solving the problem that “quickens the pulse” lies within the myth of this character.

Some months passed; then, one day when I was sick at home and reading Villani’s Cronica for fun, I happened upon the part where it says that, when the Baptistry was a Temple to Mars, its dome had an open at the top like that of the Pantheon, even if smaller, and that that opening was made so because the statue of Mars that was underneath necessarily had to remain “uncovered to the heavens.” This absurd explanation piqued my curiosity because it is blatantly obvious that using the needs of a statue to account for the creation of an opening, from which downpours that drenched the walls and drafts of air that cause bronchitis and colds could enter, is a bunch of nonsense worthy of Lewis Carroll. Besides, Villani could have easily invented something more plausible, for example that the architect wanted to imitate the Pantheon. Therefore, if he had braved the ridicule, it must be because he had copied that piece of information from a very trusted source, probably a text kept in the city archives that he frequented.

And indeed, his source merited that trust because that information had a basis in a truth that Villiani was not familiar with, but that I then was, thanks to the yellowed booklet from which I had come to know that being “open to the heavens” was precisely a feature pertaining to the god Terminus, as unique as a fingerprint or a barcode. Could there be a mistake? No, because two lines down Villiani added that the statue should not be moved, otherwise Florence would experience terrible upheavals, and this was also another unmistakable aspect of the immobile god, because if someone moved him, he would take it very badly and the end of the world would ensue.

From all of this I concluded that an ancient text consulted by Villani referred to the existence of a connection between the statue, the god Terminus and the Baptistry, and indeed with the design project for the Baptistry itself because leaving the dome open must have been a decision that involved architect, committee members and builders. It must also have dealt with a different case than that of the Pantheon, for whose great oculus no one had ever proposed the idea that it was made for a similar kind of reason.

It seemed a logical conclusion to me.

But did any of this make sense?

2 – Not a question for TV Game Shows

Driven by curiosity, I then began to brief myself about the “Baptistry question,” and very soon I realized that actually it was a topic that quickens the pulse, because it was the object of discussions that had been ongoing for centuries and involved legions of battle-hardened scholars.

In a nutshell: the classical appearance of the monument makes one think it is Ancient Roman, but the prevailing theory today is instead that it is Medieval because excavation underneath it revealed the remains of Roman houses, and their presence made it seem logical to deduce that the monument was constructed after the destruction of ancient Roman Florentia.

The endeavor to find it a plausible collocation within the Medieval period put enthusiasts on the matter to the test however, as those who have written everything and the opposite of everything about it, until finally today’s leading experts have said enough: we do not know how to say so precisely, but the Baptistry must be Medieval, trust us. This is as much as one reads in school textbooks, in disseminated texts, in glossy publications, in encyclopedias, on the internet, in travel guides, in hotel brochures, on chocolate bars wrappers, everywhere, except on TV game shows, because the research staff on duty would not know how to judge the answer of a contestant, whoever this happens to be.

Doubts therefore remain, they have only been swept under the rug, where they are in good company with a very strange legend that connected Mars not only to the Baptistry, but also to the city: as Dante reminds us, Mars was the “first patron” of Florence with sinister powers. What was the meaning of that legend? According to scholars it was all a fable; however, there must have been some reason if in Florence everyone, literally everyone, the general populace and intellectuals alike, believed in it for centuries; but what was the reason? To find an explanation, someone advanced the hypothesis of an obscure deep political-cultural plot tipped in the Medici’s favor, but the idea has not garnered the interest even of those who write fiction.

3 – Like in a Silent Movie

Thus, as I mentioned before how overwhelmed by curiosity I was, I thought to return to the monument with the wishful thinking that I would, perhaps, find some I don’t know what kind of clues there that had escaped everyone’s notice.

Having asked for the necessary permission, I visited it from top to bottom, which also elicited the curiosity of the security guards, whose way I was always in. I was underfoot so much there that one day while I was going all the way up to the lantern (an excursion that is not recommended for those who suffer from vertigo), one of them asked me politely what I was looking for. I explained that I was a teacher in Architecture and that I wanted to make a study of the Baptistry: “Oh, I like to walk with those who are studying it, no one’s ever visited up there.” I found his observation a bit disquieting: how many books had been written without first-hand knowledge of the monument?

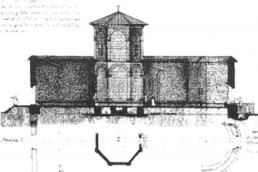

I was getting less than nothing from my visits however: I observed, took notes and photographs, but I still couldn’t understand a thing. The beautiful San Giovanni was like a silent movie whose plot escaped me. Only a few particulars about the lantern seemed to confirm that precisely on top of the dome at one point there had been an opening, but this was not new news, because no one had put forward any claims on the matter. As for the rest, utter darkness.

If the walls remained stubbornly silent, however, a vague hope came to me from mythology, because now, to the long chain of stories and legends that connected the city, the Baptistry, and the god Mars, another link had been added: Terminus. His role in the matter was still to be determined, but it was certainly an important part because he had left his tangible seal on the oculus of the dome.

I then moved my attention to the legend of the statue of Mars, and here a small light seemed to appear. Indeed, connecting it with some aspects of the myth of Terminus whose story would take too long to tell if I stopped here, I suspected that the connection with Mars was not explained by the pagan cults, but with some “martial” event. And in Florence in 406 a truly epoch-making event occurred, when the Roman army led by Stilicone stopped the barbarian invasion led by the gothic king Radagaisus who passed here on the way to sack the city of Rome.

Was it possible that the Florentines had erected a monument to remember that victory?

4 – The Dangerous Temples of Mars

In order to answer this question, I had to conduct some research about the Roman monuments erected on the sites of victorious battles. How were they made? Were there rules or models to follow? Where were those that remained? I found all of the answers in Classical Archeology textbooks. These monuments conformed with traditions that constituted the ideological bases of the Triumphal mode, the official imperial art of Rome. Although they used symbols and rites that could result in the implementation of different shapes and consistencies, from sculptural compositions to grand buildings, essentially they all conveyed the same message: divine favor for Roman arms, inevitable destiny of universal dominion of the empire, grave consequences for their enemies or those who resisted and opposed them. The Romans, as is well known, were not much for subtlety.

The nucleus of these monuments was always a Trophy, a word which today makes one think of winning a competition. For the Romans, however, it expressed altogether different concepts: the Trophy was believed to capture the deadly fury that was unleashed in the heat of battle, and for this reason they were erected where that fury, for some inscrutable divine will, had resulted in favor of the Romans, to be redirected against other enemies. Therefore, a sinister enchanted cloak hovered over these monuments, and during the Christian era it resulted in their systematic destruction because they were considered to be sources of witchcraft.

5 – Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde

In light of these clues, I ran to check if the architecture of our mild San Giovanni could be concealing the characteristics of a terrible Triumphal monument, and it was surprising to find that it had them all. Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, basically.

The first test regarded the most macroscopic anomaly, meaning the dimensions of the monument: they were completely oversized for what was supposed to be the baptistry of a small city, but a perfect fit for a symbol of the power of the Roman Empire, there was no doubt. Like a snowflake dissolved by the sun, it was resolved in this way an architectural absurdity that had been irreconcilable if considered in terms of a normal baptistry-cathedral relationship (what crazy bishop or megalomaniac could have conceived of a baptistry like that?), and even explained that atmosphere of power, rather than a pious and heavenly one, that can be felt inside the San Giovanni.

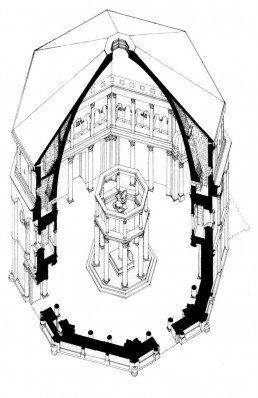

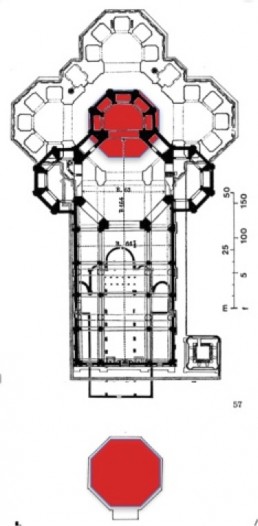

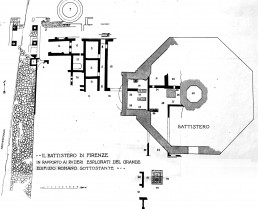

Even the central plan, the dome and the four directional doors (because originally there were four: here one would have to digress, but we must go ahead) turned out to be perfect for a structure that had to “fire” the fury enclosed in the trophy in every direction around the horizon. And if there was a war trophy in the center of the monument, one could also understand what the two massive foundations found in that location were for. A square plinth and an octagonal ring around it, supported one the statue of Mars and the other a round of columns. In the center of the building originally there was indeed a shrine, and not a great baptismal font. This is also because this font would have presented a slew of constructional incongruities that any builder could have proven convincingly to a whole auditorium of professors without them raising any objections.

There I jotted down a few sketches and I made a rudimentary photomontage, and at last the image of the original interior architecture of the Temple appeared to me – an image of power and full of meaning. Now the Baptistry as it is today looked like an empty, incomplete space, like a shell without its pearl; actually, like a weapon of war disarmed.

(continued)

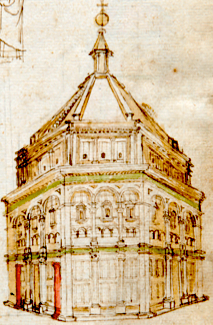

Above: The Baptistry of Florence – drawing from the Rustici Codex (Library of the Seminario Maggiore Fiorentino)

According to some scholars originally the Baptistery was so.