According to the Books, not to the Stones

In many publications and internet pages we read that the Baptistery is the result of various transformations carried out since the early Middle Ages. But if one goes inside the attics cavities to look at the walls, vaults and masonry, which can be seen without coatings, there appears instead the perfect unity and homogeneity of the construction.

There is no trace of modification.

So, who must we agree with, the talks or the stones?

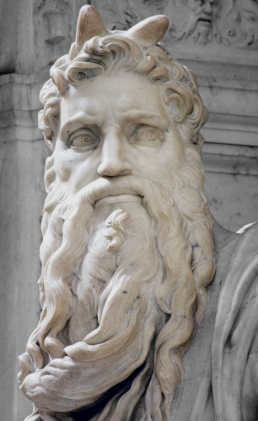

About Moses' Horns

What does the Baptistery have to do with the famous question of the horns of Michelangelo’s Moses? Nothing, of course, but there’s a reflection on the choices of the artist that I would share with my readers.

As everybody knows, the Moses of San Pietro in Vincoli has horns on his head, instead of the light rays so frequently depicted that certainly seem more suitable to represent the shine of prophet’s face on coming back from the second meeting with the Lord on the mountain.

But did Moses really have a shining face? On this point, the biblical text (Exodus, 34, 29-35) proposes a difficult interpretation: grossly simplifying the terms of a very complex and obscure question, according to some scholars his face had a terrible appearance, so that, when he realized it, he had to cover himself with a veil.

This uncertainty stems from the hard translation of a key word that in Hebrew can have two readings – ‘karan’ or ‘keren’, that is ‘light’ or ‘horns’ – whose exact meaning must be valued in the context and if it’s to be understood in a literal or translated sense.

But fortunately this thorny problem does not concern us: here we are only trying to understand the reason of Michelangelo’s choice.

Let’s start therefore from the evidence that Michelangelo stuck to the text of the Bible of St. Jerome, and that St. Jerome, between the two possible translations – light rays or horns – chose the horns, writing that Moses, on his return, had a ‘cornuta facies’, a ‘horned face’.

Michelangelo undoubtedly would have no difficulty in modeling radiant and luminous shapes, and a head with rays represented a very common iconography. Finding instead a suitable form to connote a ‘horned facies’ for a prophet without using the special effects we see today, but having instead to model it in a solid and fully convincing form, was a really difficult task.

What horns to represent? Think to any horned species of the animal kingdom, from snails to deer, and you can realize that Michelangelo was as squeezed in a corner. Anyway, he had to mold horns, which would have had a value of symbols; and symbols of this type could offer to malevolent observers easy opportunities to create embarrassment to Christians, Jews and the pope himself.

But he avoided any veiled or even distant reference to a threatening, ironic or even less demonic sense by choosing the least offensive horns: two horns just sprouted, like those of the little goats he saw grazing in the meadows of his Casentino as a boy.

Could he not choose horns? No, since he knew the Holy Scriptures very well, and had not to seem an ignorant, but also because for him sticking to the official text approved by the Church was unavoidable, given that he was working for the pope and that in the occasion he certainly had an expert biblical scholar at his side. Therefore, any possible objection on this point would not have been consistent.

But it could be also have been necessary to face some bad faith criticisms; and in this case I believe – it is only a conjecture of mine, of course – that Michelangelo could also counter them by pointing out a valid argument, i.e. that horns were an appropriate symbol for the leader of a people to conquer a new land.

Let me explain why, starting a bit far away but making the shortest path.

In the circles of Renaissance intellectuals, the myth of the Roman god of the borders, Terminus, was known. In ancient Rome, to move the boundary of a field or a property secretly or without the neighbor’s permission was a major crime to be punished very severely.

But then someone pointed out a quibble: after all, the conquest wars that the Roman people made to the whole world what were they but unauthorized displacements of boundaries? Perhaps the Roman state preached well and raced badly?

In the homeland of law, in short, an embarrassing question was posed.

Then, to get a face-saving, the Romans found a ploy that was a masterpiece of hypocrisy. According to it, they established that when a commander (dux) was appointed to a military expedition, during his performance he became the god of the borders himself, Terminus – the strange god who, as someone perhaps remembers, had a symbolic relationship with the construction of the Baptistery. Therefore, as long as he was on his duty, the dux had the divine power to move the state boundaries, that is, to annex the conquered territories, because the gods of Rome had guaranteed to the Romans the conquest of the whole world.

So, the dux would temporarily become the instrument of this divine plan becoming Terminus; and since Terminus was represented as a boundary pole with the head shaped as a fork, also from the dux head two horns were expected to sprout out; and as it was obviously impossible, they remedied by putting on his head, in ceremonies and triumphs, an oak crown to hid them, and everyone pretended to believe it.

Michelangelo therefore could find an answer even to the malicious objections by referring to classical traditions; and in this regard it seems significant that his Moses’ horns are clearly spreading out like a fork, differently from the normal horns on the skull of goats.

A Spite of the Canons

The first hospital in Florence was named after St. John the Evangelist and was built between the Baptistery and the cathedral of Santa Reparata in 1040. To us it seems incredible that a building could be built in such a small space, yet the news is certain and documented: the hospital was right there, and it was a real stumbling block, so much so that everyone in the city, including Dante, called for a long time for its demolition, but it suited only in 1298.

To find an explanation for such an illogical fact, first of all we can look at the plans of ancient Florence to get an idea about the position and size of the building. Considering to leave a minimum space in front of the cathedral, we see that the hospital area could be about 15 x 90 ft, that is 5-6 rooms posed side by side; therefore it had to be an atypical hospital, because at that time hospitals were usually built around a cloister, but it was here impossible given the limited space. This renounce to the typical form to get fitted to the place lets us understand that they really wanted to occupy that precise area, otherwise they could look for a more suitable space beyond the nearby walls, where there would have no such problems.

About the building, we must consider that a hospital at that time was very different from today: it was only a shelter for poor and sick people, without any purpose of treatment.

An extremely simple building is suggested also by the news that in its last years it became a warehouse. Then, since in the modern excavations no foundations of it were found, we can guess that they had to be minimal and superficial, and support little weights, in proportion with an only ground floor building, wooden roofed, made without care and probably in a hurry.

Above all, however, the location so close to the Baptistery – about 6 ft away – clearly means the will to create a barrier in front of its east door, at the present called Porta del Paradiso. Here is the key to solve our problem: what the canons were seeking was a separation from their neighbors. And actually at the time there was a heavy dispute between the simoniac bishop, who had the possession of San Giovanni (probably also claimed by the Florentine Comune), and the canons of the cathedral who instead had the possession of the Santa Reparata and were supporters of the reform of the church.

It is clear that the Porta del Paradiso had a strategic role for the bishop because of its facing the cathedral, to which he would connect in order to regain its control. But that door became then unusable, and remained so for a long time: having been closed the original west entrance to create the apse, the south door was usually used for worship and ceremonies, while the north door was not suitable for processions and rituals because too close to the city walls.

In conclusion, the construction of the hospital was the result of this situation: the bishop wanted to create a relationship between San Giovanni and Santa Reparata, but the canons, who owned the latter, were opposed, and managed the hospital as a placeholder of their property rights making a spite to the bishop. It was also significant that they had named their hospital after St. John the Evangelist, as an alternative to the other St. John next door.

After a few years, in 1059, the intervention of Pope Nicholas II would have brought some order in this very complicated situation; but the opposition to the removal of the hospital was still stubborn and lasted two and a half centuries, demonstrating the canons’ will not to give up their rights. This resistance can be explained by the fact that they were representatives of a minor clergy that was present in Florence for centuries, and that did not want to renounce the rights they had acquired by providing for the care of the people during the long periods in which the bishop was absent; but this is a matter for those who study the history of the Florentine church.

In the paving of the square today are visible in front of the cathedral the position marks of the Santa Reparata porch columns, whose foundations were found in some excavations of the last century.

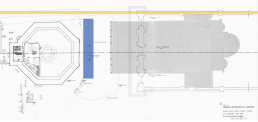

Plan of the Piazza del Duomo area showing the positions of the Baptistery of San Giovanni, the current cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore and, in grey, the ancient cathedral of Santa Reparata. In the plan are also indicated some archaeological findings excavated under and around the Baptistery. The outline of Santa Reparata includes the portico on its facade, whose columns position is also marked. In blue is the probable position of the hospital of San Giovanni Evangelista, and in yellow the alignment of the walls of the Roman city; the left transept of Santa Reparata seems to partially overlap them, but it is a medieval extension.

(Plan from C. Pietramellara)

The Baptistery Umbrella

“In the year of Christ 1150, the ‘capannuccio’ (little hut ) raised on columns was made”, wrote the chronicler Giovanni Villani in the first half of the fourteenth century, referring to the construction of the marble lantern that crowns the Baptistery at the top. But why does he call it ‘little hut’ – words that implie a judgement of minor qualification – instead of using the more appropriate term of ‘lantern’? And why specify that it is ‘raised in columns’? Perhaps the one that was previously there did not?

Doubts that deserve an attempt at explanation.

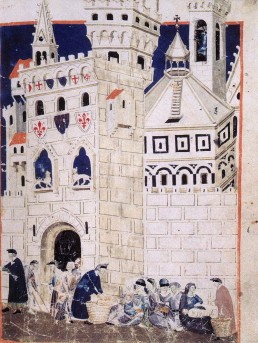

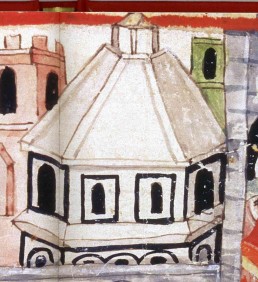

Let’s start from when the problem arose, that is, when the dome was built with an opening at its top – an ‘eye’ – through which the rain fell into. This hole caused, in addition to obvious inconveniences, a damage of the masonry, and it is very likely that, as soon as the building was used as a church, they tried to create a protection. This protection wouldn’t be in masonry, because on the roof no traces suggest that: if it was made, it was probably in wood, like a shelter on small columns anchored to the marble but with the sides open. Some miniatures in the Chigi codex (mid-fourteenth century), as far as they can help us, indicate this.

A similar artifact would have been appropriate to call it a ‘capannuccio’; thus the term remained to denote what was on top of the roof of the Baptistery, as that of ‘scarsella’ remained to the strange rectangular apse.

If we now take a look at another miniature, that of the Codex of Biadaiolo, datable to around 1340, when the ‘capannuccio’ had already been “raised in columns” from a couple of centuries, we see that the lantern is presented without glass frames; therefore windy rain still penetrated into, threatening the stability of the large mosaics. This can be understood from a detail diligently noted by the miniaturist: at the foot of the columns we see a protection made with laths or slabs of marble placed to prevent the water of the shelf from draining into the interior. In short, the ‘capannuccio’ guaranteed a protection that was still unsatisfactory. Glass windows were necessary.

We don’t know exactly when they were posed, but the problem must have been well known to everyone for some time, also because the infiltrations made the work of the mosaicists very problematic. So why the delay?

Probably the reason was that, in order to insert the stained-glass windows, the capitals had to be chiseled, and this had to be done with great caution because the weight of the trabeation and the cusp loaded on them. Indeed, the insertions in the capitals caused many breakages, which were remedied with many similar pieces that document that there were several other capitals available, and all of them evidently could only come from the original aedicule that surrounded the ‘statue of Mars’ inside the monument.

In the title: detail of the miniature of the Codex Biadaiolo representing the episode of the Florentines giving bread to the poor people expelled from Siena by the great famine of 1328-30; note the lantern without glasses.

Below: the same miniature in its whole and a detail of the Chigi Codex of the Cronica (f. 80r) in which we see, at the ridge of the roof, what really looks like a wooden ‘capannuccio‘ (little hut), both for the shape and for the color.

In the photo on the left we see the breakages of the lantern capitals due to the forced insertion of the glass frames and the dowels with which they tried to remedy.

What Stood in the Center of the Baptistry?

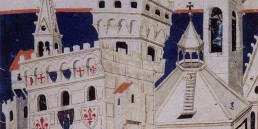

What stood above the foundations found in the center of the Baptistery, where we see an area of the floor devoid of marbles?

The prevailing interpretation is that there was a baptismal font, but this idea has no sense in a construction point of view: those foundations would be extremely oversized to support a very light weight. The great architect of the Temple-Baptistery could not make such gross errors that not even the last of his workers could make. This idea, in short, is an insult to his skillness; and let us not speak of other even more wrong ideas.

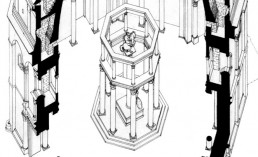

But if we look at those foundations as made to support the column of the ‘statue of Mars’ and its aedicule, everything would find a constructive logic and perfect proportions.

Indeed, these foundations suggest not a baptismal font but a trophaeic aedicule; and curiosity urges us to try to imagine how this aedicule could have been made.

I tried to do that, also following the image painted by Vasari in Palazzo Vecchio to represent the Temple of Mars in its original form. But if Vasari made a mistake because the Temple originally could not have been the form he imagined, that image is instead perfectly congruent with the foundations mentioned above, but which he could not know at his time. Is it a case? Or did Vasari have some document from which he drew those forms? Or perhaps Borghini suggested them to him on the basis of a document he had?

We don’t know.

Anyway, the foundations can give us some suggestions, as we see in this a fascinating image.

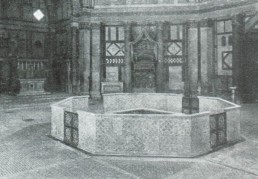

The baptismal font as it was imagined in 1921 on the occasion of Dante’s celebrations.

Matters of Details

Arches of the apse, lantern capitals with spindles, Roman mosaic floors, walls in false, structural connection in the attics: in the Baptistery many details deserve an explanation.

1 – A Detail in the Scarsella

In the Italian dictionaries: Scarsella, a flat pouch which in the Middle Ages was hung from the belts; in architecture, the square apse of a church.

I think that the first architectural scarsella was that of the Baptistry, and that the name was given because of a typical Florentine mockery. When the Baptistry was a ‘Temple of Mars’ it had its entrance on the west side, just in front the current archbishopric, and the entrance was a loggia that then was closed by three walls in order to convert it into an apse. The result, however, was not met with praise by the Florentines (did you think they would?): in their eyes that closure gave the effect of one of those flat bags – a scarsella, indeed – that they wore on their bellies, which in this case would mean on the potbellied building, with all due respect. All of this occurred in 1202. The ironic nickname came from that and went down in history.

The rectangular apse is thus a Romanesque part, and its arches are perfect semicircles like all of the other Romanesque churches of Florence – San Miniato al Monte, Badia Fiesolana, San Salvatore al Vescovo, the Collegiata in Empoli.

Now, if the Baptistry were Romanesque we would expect that its arches would also be semicircles. And yet they are not: there are semicircle arches in the apse, but not in the body of the building, where all of the façade’s second order arches present a notable raising of the impost: and this is a feature used by Classical architects in order to make the arches appear slim, light, and elegant.

Even this detail tells us that while the scarsella is from the Medieval period, the Baptistry is not.

2 – A Detail of the Capitals

Some Corinthian capitals of the lantern at the top of the Baptistery have the volutes that do not lean over the acanthus leaves, but are detached from them. Nothing unusual, except that the volutes are joined to the leaves by small spindles that are part of the same block of marble.

This singular and very rare feature required an extremely accurate workmanship, given the obvious risk that a chisel blow badly given could break that small drop of stone.

I think that the purpose of the spindles was to create slots for to pass some festoons strings, and this suggests some civil celebrations more than religious, although these cannot be excluded.

Similar capitals are also seen at ground level, next to the north door, and while those of the lantern have been moved from another location and reassembled, this one instead is intact and certainly in its original location.

These small but significant demonstrations of great skill by some humble stonemasons have never garnered the attention of scholars, but if they had, do you think anyone would have attributed them to Romanesque art?

3 – A Detail in the Mosaic Floors

When the Temple of Mars was built, a strong foundation plinth was made at its center to support the column on which had to be placed the statue of the god – or rather of the character who was believed to be Mars. The plinth was discovered in the early twentieth century excavations, and then it resulted that it had been built removing part of the mosaic floors around it to pose it on the compact ground – the level of the Roman Florence – which was found immediately under, so that no deep excavation was necessary. This would not have occurred if the plinth had been built some centuries after the Roman city, because some layers of soil would be found over the floor level. On the contrary, as can be seen, when the plinth masonry was realized, the mosaics were still intact and leveled: that is that the floors had been used until very little time before, otherwise the rains and vegetation would have broken them up as always happens in a very short time.

In short: this other detail confirms that the construction of the Temple took place when the Roman city still existed and was not devastated by the barbarians.

So, the archaeologists of a century ago made a big mistake, confused as they were by the enthusiasm of having discovered the finds of Roman Florence. But since then, non one of the scholars who published mountains of books on the topic tried a check on what those archaeologists wrote.

Alas.

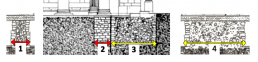

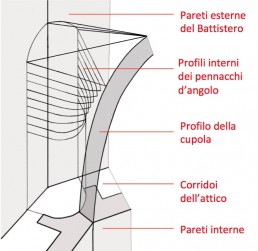

4 – A detail in the attics

Building false walls goes against any rule, yet in the Baptistery the walls of the attic are false towards the inside. Even if this detail can be seen very clearly from the square, it has always been ignored by everyone, probably because no one could explain it. A few years ago, however, Giovanni Pelliccioni gave the key: the Roman builders, he wrote, in order to counteract the outward thrusts existing in the lower part of a dome, tried to surround its base with walls unbalanced in the opposite direction – that is, by placing them false inward. This is the reason of an expedient that has no solid scientific basis, but seems to have worked very well in the last 1500 years.

In the attics we can see the cap that creates the thrusts: it looks like the back of a whale that emerges from the dark abyss but is blocked by the strong buttresses that surround it. It is exciting to think that even Brunelleschi was up here to study this perfect structural mechanism that here is offered to our sight without the veils of coatings and mosaics to be admired in its constructive logic.

Then, looking closely, we see that the buttresses have only occasional connections with the dome, with drafts that rest on it without penetrating into its thickness. This means that for the architect was not very important to joint the dome to the buttresses as the rules of good building would require.

Strange, but perfectly logical. The architect had a very clear idea about the static behavior of these structures, and knew that, being outwards the dome thrusts, to counteract them it was sufficient to surround the dome with solid elements, no matter if connected to it or not.

This way of reasoning was not that of a Romanesque builder.

Up to down: arches of the scarsella, of the 2nd order of the facade and of San Miniato al Monte.

A lantern capital with spindles and a detail of it.

The central area of the excavations: on the left you see the edge of the plinth of the ‘statue of Mars’, and all around the mosaic floors of the Roman houses.

Above: the retreat of the attic seen from the square and a picture of the under roof gap in which we see, on the left, the extrados of the dome and on the right a buttress that is not fitted in it.

When in Florence Greek was Spoken – 1

This text is about a research I started many years ago and still haven’t finished. Indeed, it is probably impossible to finish it because it is very complicated and the available data is very uncertain and incomplete. But the argument is suggestive: I therefore ask for patience and understanding. Thanks.

When in Florence Greek was Spoken – Part 1

Syrian merchants, Byzantine missionaries, Barbarian soldiers. And the Florentines

A Brief Premise:

When Florence was called Florentia, Florentines spoke Latin, but not all of them did: in fact, for a long time, groups of Greek speaking people lived in the city. They were immigrants from the Middle East: businessmen, soldiers, men of the church, they were all people who played an important role in the difficult moments in the history of the city. Some traces of their presence remain to us in a few sepulchral stones from the fifth century which were found by excavating under the Church of Santa Felicita, near the Ponte Vecchio, as well as a few less direct testimonials. A few stories about the city’s church in fact, lead us to suppose that, from the seventh century onwards, there was a Middle Eastern ministry present in Florence that brought worship practices from their homelands to the banks of the Arno. When we expand our vision and see the big picture, it seems that these presences were bound together by a continuity over time which fits in with the general phenomenon that saw many people follow a path that, crossing the Mediterranean, brought the Middle East not only to Florence, which interests us here in particular, but to other places whose coasts overlook the mare nostrum; a path that was tread many times, with different aims and in different circumstances, and it is significant that those people came from the same geographical area and that they didn’t express themselves in their mother tongue, but rather in the international language of the time: namely, Greek.

Three groups of “Greeks”: merchants, soldiers, missionaries

The first group of these “Greeks” examined here is the one we have the most direct testimonies of, and whose presence in the city gave rise to the idea of their important role in the evangelization of the ancient Florentines, even though they were – at least it is believed that – simply merchants. A theory which I think is only partly true.

The second group is comprised of soldiers: we even have some stones left from them that document both their presence in the city at the time of the war between the Goths and the Byzantines in the sixth century as well as their Middle Eastern origins.

The third group is comprised of men of the church, who were also Middle Eastern but spoke Greek and came to the city in small numbers at first but in time became part of a missionary movement that under the Lombards concerned not only Italy: a movement that has remained poorly understood, but whose traces are rediscovered in Florence in the eleventh century, when the Greek prayers and rituals those priests had brought were definitively abandoned.

Formulation and Limitations of the Research

In this text I will seek to interpret the few data that we have in accordance with a rational perspective, even if it is inevitably influenced by a subjective interpretation of the few data points available, for which it is inevitable that there be margins more or less open to interpret that data differently. It should be taken into account, however, that many of today’s more diffuse publications stem from studies, whose bases for the arguments that we are talking about here, were laid long ago, but those bases do not always turn out to be solid, which is easy to test. This will be accounted for case by case in these pages, so that the reader can make their own opinion.

Last but not least, why Santa Felicita?

The last section of the text talks about the cult of Santa Felicita and the story of the church dedicated to her that would be, according to some, the first one constructed in Florence. That is certainly inaccurate, since San Lorenzo was the first Florentine church, but Santa Felicita is certainly among the oldest and the cult of the saint is certainly older, which presents some intriguing elements, given that two saints exist with this name and that the one venerated in Florence (in addition to other saints) is connected to the very unique cult of her martyred sons, the seven Maccabees. The continuous presence of this church and this worship, projected on the background of the city, can shed some light on some very dark times. A bit of light, even if it is weak, indirect, or reflected is still better than darkness, and it can help to correct some errors that are read here and there in texts on the local history, which often get repeated only because they took the information unquestioningly.

(To be continued in the following…)

Allegato

The spaces below the Church of Santa Felicita, where the remains mentioned in the text were found (photo by M.C. Lombardi Francois).

Marbles, Plumbers and Shipping Agents

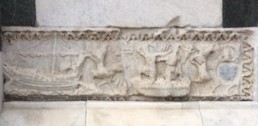

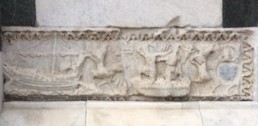

Two Roman marbles pique the curiosity of visitors to the Baptistry. One is a walled bas-relief on the southern façade of the scarsella, at the bottom, which depicts two scenes: one of trade and the other of a grape harvest. On the left we see an anchored cargo ship with some men who are unloading some merchandise, and on the right other men who are crushing grapes in vats. Therefore, it does not concern a naval battle as naively guessed by some.

It was also thought that the grape was a reference to the Eucharist, given that the marble is in a religious building, but this interpretation seems far-fetched.

So, let’s move on to more objective observations.

By looking at this marble carefully we understand that the slab was originally longer, and that it was then cut (rather badly) in three parts, two of which are those that are seen now and that, when juxtaposed, have the right width to be inserted into the layout of the façade’s cladding. The third piece was thrown away, and this means that the scene depicted in the bas-relief didn’t interest anyone, and that the workers only cared about having a valuable marble piece and that it had to be the exact size for what they wanted to do.

Was it a place-marker for a burial? It doesn’t exactly look like it, considering the quality of the handiwork, the depicted scenes and the lack of any writing; and then in that case they could have done something less complicated and without having to deal with the layout of the cladding of the wall.

All of this suggests instead a repair job made to close a hole in the cladding: persons who were anything but sophisticated could have thus taken the first antique piece of marble that they had at their fingertips, which had been deemed suitable to be on a monument that was also ancient, regardless of what it depicted. What is called a ‘matching color patch’, in other words. The patch must have been made then when Roman marbles could still be found in the city, and since the scarsella is from the beginning of the thirteenth century, all of that would be dated to those years.

We don’t know what could have caused the gap: it could have even been an unintentional damage, given its location on the bottom, but I want to push myself to make a rather quirky hypothesis.

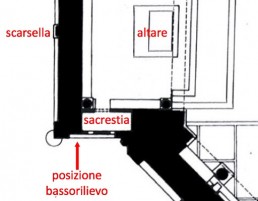

At that time, they were working on adapting the monument to its function as a baptistry of the city. In that context they had to set up a sacristy somewhere, and this was the small room that is there just on the back of our marble. Then in a sacristy it was important to have a water supply, and making it with a minimal impact of the plumbing. All of the connections to the city’s waterworks were on the west side, close to that angle of the sacristy: thus, they decided to pass some tubes through there, necessarily at the bottom. It was not an easy task, also because they had to avoid cutting or damaging the external plinth. The wall of the small sacristy was however – and it still is today – rather thin, and because of this, as always happens, it caved in; so, they needed to repair it immediately. And here we are.

Could that be the case?

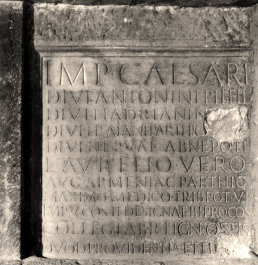

Yet I also have to say something about a marble slab with a beautiful inscription from the second half of the second century that is inside the baptistry, in the gallery. This marble measures approximately 1 square meter, and was used as a railing for one of the choirs. On it we read that it was made by the collegium fabri tignari of Ostia (a woodworker’s guild) in honor of the rulers of that time to whom – as can be understood by other similar inscriptions since this marble is partly broken – the guild expressed gratitude for some favor they had received (that’s to say, a profitable contract).

In the 1700s, this stone was believed to be proof of the barbarian origin of the monument by the scholars of the time. They explained that this was why so much “disdain” to use it as any kind of construction material was shown. In reality these scholars were very learned in theories but didn’t know much about construction practices because they didn’t consider the fact that on a building work always prizes doing what is most convenient if will get the same result. And thus, if there was marble available and that wasn’t of use to anyone, it could be easily employed where it was useful to do so, and this was not only done in the time of the Barbarians, obviously.

Therefore, having sorted out the scholars’ preliminary observation, we need to ask ourselves what such a so heavy thanksgiving message from a guild from Ostia was doing in Florence.

But Ostia was a very busy port, where certainly ships that brought marbles from the Aegean countries for the Temple of Mars would have stopped. Perhaps because of this, given that the collegium had existed no more from some centuries and that such a beautiful piece of smooth marble would surely be useful for making many things, someone took it, paid (perhaps) for it, and brought it off. Once it got to the worksite in Florence all they had to do was modify it a little, and here it was.

To make scholars argue.

From top to bottom: the bas-relief of a ship from the scarsella; detail of the floorplan of the ground floor of the Baptistry; the stone with an inscription from the second century enclosed in the railing of a choir in the gallery.

A Wandering Zodiac

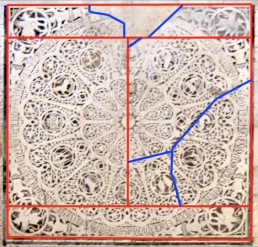

On the floor of the Baptistry, near the Gates of Paradise, two large square marble slabs inlaid with zodiacal and zoomorphic figures make a beautiful show of themselves. They are about 3 meters per side, and because both present similar features, it can be thought that were constructed together to decorate the flooring.

One of the two (let’s call it ‘marble slab #1’) has in the center a white disc with no decoration, and around it two wide rings with inlay figures. These rings are precisely divided with radial cuts that respect the figures, so that each part could be inserted correctly into the composition. And a point is very strange: in a marble slab filled with figures and motifs, the focus of the composition is entirely mute and inexpressive, without any figures.

The other slab instead (‘marble slab #2’) shows a rich series of depictions centered on the theme of the zodiac, with the image of the sun at its center surrounded by a palindrome latin verse that celebrates the star: “En giro torte sol ciclos et rotor igne.” [“I, the sun, with fire make the spheres turn as I myself turn”]. And here the strangeness is that, despite the sun being at the center of the geometries and the key of the symbolic message, its image is exactly cut in two. That attests some care taken in cutting it, which nevertheless, as was inevitable, did damage the smaller pieces of the inlay. Even so, it would have been easily avoided if they had thought from the beginning of creating a rounded panel, with the correct measurements to contain the figure of the sun, which is rather small, and the palindrome written around it. Likewise, the other cuts that we see on the marble slabs do not correspond with the patterns, which are crossed with a certain care but without any scruples.

In conclusion: if for marble slab #1 they took care in coordinating the cutting and patterns of it from its inception, for #2 it was not like that: this marble slab must have originally been all one piece and was divided only at some later point. This could be explained if there had been a relocation of the slabs: #1 could have been dismantled and easily reassembled, while with #2 this would have been problematic given its size. For that reason, they could have resorted to a very hasty solution by trying to limit the damage, but they had great difficulty in finding the incision lines that would have the least impact and be the easiest to carry out. And in fact, here in the #2 slab the incisions, which divide it into four parts, do not have radial paths like those in #1, but only linear ones, which did not involve any problems of geometry.

So why was it relocated?

I will attempt an explanation.

Originally, the Temple of Mars had a west-facing entrance that opened out onto the main road of the Roman city. When the Temple became a church, they tried to create an apse in many ways, but unsuccessfully, so in the end they decided to simply close that entrance and use instead the south door, since the other two were less suitable due to the narrow passages in the outside.

When the church became a baptistry, in 1128, it was necessary to make the east door the main entrance because it was facing the cathedral, and so a lot of work had to be done on the building. In addition, they thought of placing on that side also the beautiful floor panels that originally decorated the path to introduce visitors to the Temple. In this way they would have lent themselves very well to underscoring the importance of the new entrance of the Christian building.

Of the two panels, the one with the zodiac was evidently conceived in order to offer a key to reading the symbols of the building to those who entered it, because the space of the Temple wanted to express the destiny of glory of Rome in a heavenly and eternal projection. But what was the purpose of the other one, which offered only the view of an empty disc?

The empty disc itself helps us understand its purpose: like the porphyritic red disc near it, which was made for the emperor’s throne and is the same size, this white disc was also meant to indicate his position when he would receive, being at the entrance, the homage of the Florentines who were crowding the piazza in front of it.

But that is not everything, because one must consider that in 1128 the altar must certainly have been there already, given that the building had long since became a church, and it was placed on a presbytery raised by a few steps more or less as we see now. Therefore, it being inconceivable that the altar and presbytery were demolished to bring back in light the panels on the underlying floor, one must conclude that those panels had already been moved from their original placement and put away somewhere. What happened to these marbles must have been the same that happened to the marbles of the lantern and to the column of the statue of Mars: when, in the fifth century, the Temple became a church, all of the prized marble was dismantled and stored nearby, to then be reused if the occasion presented itself.

This happened in 1128 for the panels, and it was probably then that they were fractured.

Above: diagram of the incisions (in red) of marble slab #1

Below: diagram of the incisions (in red) and of the fractures (in blue) of marble slab #2

Detail of the sun at the center of the slab with the zodiac. The incision damaged the inlays in the central part of the solar crown.

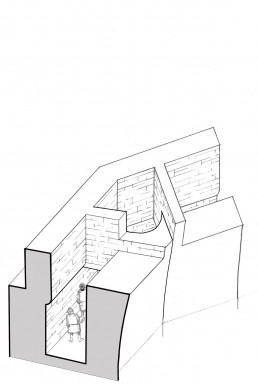

The Hidden Geometries

More than from laboratory tests on samples of materials, always subject to doubts of all kinds, we can understand if the Baptistery is Romanesque or not by making a simple reflection.

In order to construct a building, you have to create a design, and to create a design you have to possess a proper knowledge of geometry. The Baptistry, with its seemingly simple shape, hides very complex geometries, and if it is believed that is a Romanesque work, it is therefore logical to ask oneself if these geometries would have been within the reach of a Romanesque architect.

The answer is obvious: absolutely not. Believing that a Romanesque architect could create the complex geometries that are present in the Baptistry is like believing that a bicycle mechanic could tune-up the motor of a Formula One racecar.

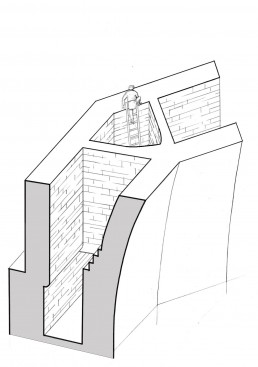

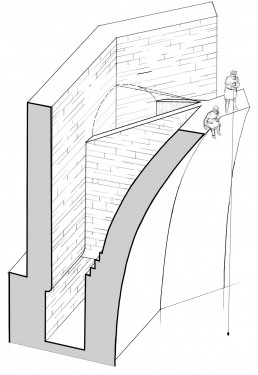

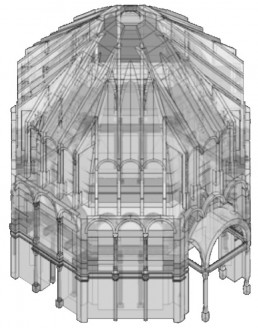

In the Romanesque world there were no architects able to conceive, represent and manage the three-dimensional geometries that we see strictly applied everywhere around the Baptistry, but especially in the loft, where the architect had to face three different geometric patterns – that of the octagonal prism that constitutes the body of the building, that of the cylindrical surfaces of the vaults of the dome, and that of the inclined planes of the pitches of the pyramidal roof – as well as direct the workers about how to achieve with absolute precision the various wall structures converging at the top the roof. A hard challenge even for many of today’s graduates.

This is not an aesthetical evaluation of artistic skills: it is an objective matching of technical knowledge. In the Romanesque period there was no one who could devise and manage all these geometries together – period.

I can understand how those who have studied literature or art history may not have considered this aspect, and, in formulating a dating of the monument, that they didn’t think to ask a few questions about the geometric knowledge of its designer. But the architects?

(Below) – Stages of the construction of the corner compartments, where the curvature of the vaults of the dome begins. In order to successfully overcome this delicate passage a deep knowledge of geometry was necessary, certainly far superior to that of any Romanesque builder.

In the heading: detail from the axonometric projection by G. B. Milani (1918)

The Geometry of the Baptistry (drawing by Roberta Lovino)

The geometry of one of the corner compartments of the loft