The Extremes of Dwelling

In my course of Distributive Characters of Buildings, to introduce some topics of dwelling I first made the students reflect on a point: that our projects do not only create more or less beautiful things, but also deeply affect the very lives of people.

Before submitting some examples taken from everyday life in our houses – living rooms, bedrooms, elevators, stairs, toilets and so on – I thought of introducing the topic by bringing two extreme examples, one for good and one for bad.

For the bad, it seemed obvious to choose Auschwitz: after all, it was somehow also a particular ‘dwelling’. Naturally, I would have faced such an important and complex issue from a very defined and limited angle, that of the project.

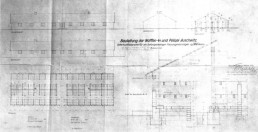

I found a very well-documented book on the subject (R.J. Van Pelt and D. Dwork, Auschwitz – 1270 to the Present), by which I learned that Himmler had chosen Auschwitz not only for the purposes we know, but also to make it, thanks to the work of the internees-slaves, a productive center to finance the activities of the SS. For this reason he had a staff of technicians to draw up urban plans (Auschwitz was at the center of a group of satellite camps) and detailed building projects, and many of those drawings miraculously escaped destruction. From them one could see how the project of this camp had been meticulously articulated according to the teachings of Rationalism of the time, precisely defining connections, green areas, placement of the buildings, functional division of the zones, construction details of barracks and furnishings… in short, everything, even the modifications that became necessary to the crematorium installations in order to face the enormous number of dead.

In these project designs were evident the devices used to destroy not only physically but also psychologically the inmates: for example, at Birkenau had been provided only one latrine for 32,000 women, and it was a small hut that could be used only at fixed times, and to be reached after long queues with feet sunken in excrements. Inside this shack there was a pit with boards thrown across it: on these boards the inmates perched tightly together and often in the grip of dysentery, soiling each other’s rags in a nauseating stench.

Now, the architects and engineers who had designed such a ‘toilet’ could not claim their fairness saying that they were unaware, that everything was casual; and let’s leave aside any talk about the gas chambers, which had punctual and documented building and technological modifications to speed up the ‘work’. In short, the criminal intention of those technicians who had scrupulously used their knowledge to design evil was evident, and I emphasized this in classroom, finding great interest among the students.

Then, years later, I learned that Prof. Van Pelt had been called as an expert in a trial against David Irving, the leading Holocaust denier, and found himself involved in a heated controversy. The deniers in fact sought every argument to challenge the idea of a planned mass extermination, and the debate was getting bogged down in a discussion about the methods with which history is written and the reliability of testimonies and documents. History is always written by the winners, right? – they argued – and even in this case they had gone far beyond the reality of the facts: there was no proof that millions of people had died in the camps, nor that those ovens could reduce to ashes such a large number of corpses. The discussion touched on very technical aspects, and even came to take samples from the walls of the gas chambers, to check if they were really soaked with cyanide gas – the famous Zyklon B – which to limit costs was used very sparingly in doses despite the fact that this dilution involved a lengthening of sufferings.

But a very concrete and decisive argument against the deniers came just from the plans of Auschwitz, produced in court by Prof. Van Pelt, because those drawings demonstrated beyond any doubt, both for the creation of clearly functional buildings, and for the meticulous organization given to the whole – that is paths, functions, flows, dimensions, all studied with the prope manuals’ criteria – the purpose of those projects. Just as the drawings of an engine make a mechanical engineer understand how it works and its performances, so the Auschwitz project, analyzed by any technician, provided a very clear evidence against those who claimed that the extermination camps were just a fake.

If the choice of the most negative example had been obvious, I found myself in a bit of a quandary when it came to the positive one. I thought about the Jacaré School, various places of spirituality, Dr. Schweitzer’s hospital and so on: all examples were worthy of attention, but not exactly in line with what I intended. While searching, I came across a topic that had great appeal, and I dwelt on that, though perhaps a bit off topic: the house of the Last Supper. What did it look like?

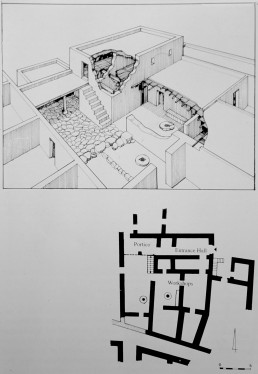

The endless paintings depicting that event are obviously figments of the imagination, but I was interested in knowing something of the building reality. What could be said was very little, and it was obtained by cross-referencing the studies of archaeologists with some hints we find in the Gospels. In a book (Y. Hirschfeld, The Palestinian Dwelling in the Roman Byzantine Period) I found illustrated various types of houses of the time, and also those that had the famous ἀνάγαιον (anàgaion) mentioned in the Gospels: a room on the upper floor, which had a use similar to the living rooms of today and was reached from the courtyard by climbing an external staircase.

This house, which was located in the southwest part of the ancient center of Jerusalem, was the first church, in which the apostles withdrew after Golgotha and where Pentecost took place. The property probably belonged to the family of the evangelist Mark.

The house that hosted such important events was therefore a very simple one, similar to many others.

Because good is made of small things.

(Above) The architects and engineers of Auschwitz in a group photo from 1943 (Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum).

A table from the first Regulatory Plan of Auschwitz, dated June 1941: in the center the main camp with the appeal square, the inmates’ barracks, the prison, the infirmary and the crematorium; on the right the lodgings of the SS and the station above; on the left, the command of the camp, warehouses and laboratories (Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum).

One of the executive projects for the Auschwitz prison barracks. You can see the accurate executive definition of the works to be carried out, which were then described in the specifications and calculations that completed the projects; the originally planned capacity of 550 prisoners for this hut-type was quickly increased to 744 (from Van Pelt – Dwork).

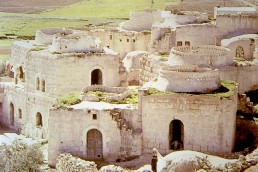

Examples of Palestinian homes similar to those of Christ’s time.

His Last Shower

At the end of the winter I noticed that one of my students wasn’t coming to lessons, wasn’t submitting works to review, nor sending emails. All that could compromise his year work not permitting him to sustain the exam in the summer session. I asked a few classmates about him, and the answer froze me: he was dead.

Dead? Possible?

Yes, it was possible: we can die in our twenties. And nobody even had an idea on what happened: he was in good health, he hadn’t committed any rash actions, he didn’t use drugs, he hadn’t been involved in dangerous activities… Nothing at all: he was a normal boy who studied and led a regular life.

So what?

They told me that one Saturday night he had arranged to take a pizza with friends, but he didn’t arrive. The delay went on, and so, in the end, after several unanswered calls, they went to the small apartment he was renting – a couple of rooms in an old house in the city center – and found him into the shower. No traces of other presences, of break-ins or even less of violence: nothing at all. All the rooms were in order.

In the following days the police made several inspections with no avail. Then finally they noticed inside the small bathroom, in a corner, a very thin slit running between the tiles. So they could understand what had happened. That damned slit was connected to the old flue of the stove of an apartment below, which in that cold day had been in full operation, and from there had come out the carbon dioxide that soon saturated the small environment thus making the unfortunate boy fall asleep forever.

Since then I have never forgotten to recommend to my students to design the flues with all due caution, possibly inserting reliable stainless steel pipes.

To Know My Students

An Art historian of our Faculty was about to fail a student when he asked for a last chance. Maternal instinct suggested her an easy question: “Tell me about Giotto as architect”. Too much for him: “Please, please professor, don’t ask me about minors”.

I often thought back to that anecdote when I entered a classroom at the beginning of a course, asking myself what level of culture and knowledge could have those kids who expected me to teach them how to create a project. How many of them could hid behind a friendly and smiling face unfathomable abysses of pure ignorance?

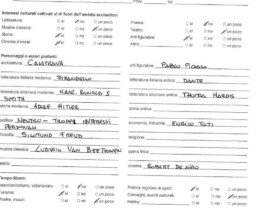

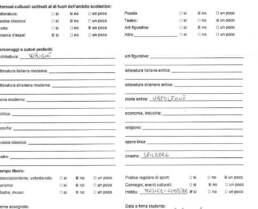

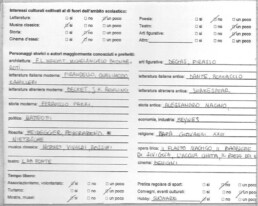

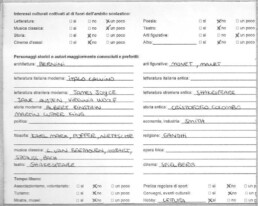

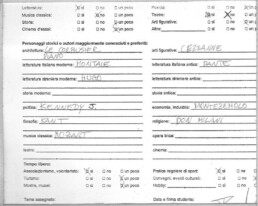

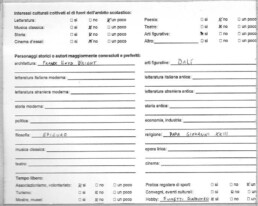

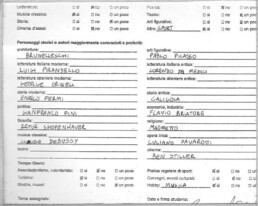

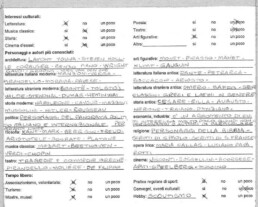

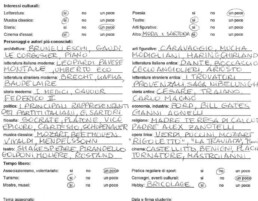

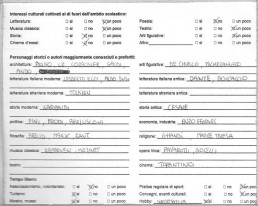

To be properly related to my audience, one day I asked the class to fill out a form in which, apart some bureaucratic information, I submitted a small survey on cultural interests and extracurricular activities. I repeated the experiment for a few years, collecting an interesting dossier.

The majority of the answers revealed an evident poor cultural background, with little in-depth study and large gaps and a frame of values drawn almost exclusively from the mass media rather than from reading books or attending to cultural groups or so. The repeated misspellings of the names of authors or characters, then, made it clear that the information was drawn mostly verbally, ‘by ear’, and with a poor level of attention.

This gap between spoken and written language was already known to me from having read several reports by students in which they repeated with the utmost indifference syntactical and grammatical mistakes of all kinds. So I had deduced that today the concept of mistake is very different from that of the older generations, and much more elastic. Today seems that it is enough to make oneself understood, and how the result comes out it has poor importance.

Faced with this majority of students who proved to be deep below the threshold once required for the secondary school, there was, however, also a substantial minority who demonstrated a lively base of interests even outside the field of study, and often an appreciable and comforting commitment to daily life and voluntary activities.

Anyway, my long experience didn’t draw me in a negative judgment about the students, apart from some very rare cases: but I could not say the same about the service that had evidently been offered to them by the educational institutions in secondary school. And I do not talk about the university.

I report here some of those forms, duly got anonymous, in the parts related to the survey.

When I Met Carlo Lucci

On March 18, 1969, in the late morning, I met Carlo Lucci coming out from our Faculty of Architecture in Piazza Brunelleschi. At the time, Professor Lucci was an Italo Gamberini’s assistant, and since he before had been my tutor for two years, he remembered well that clumsy boy who was able to draw despite having studied not in an artistic high school but in a classical one.

He greeted me cordially and asked what I was doing.

– I’ve just graduated and now I’m looking around.

– Why don’t you come over to help us in the Institute?

My unmemorable university career began in this way, meeting a person who on impulse made a small bet on me.

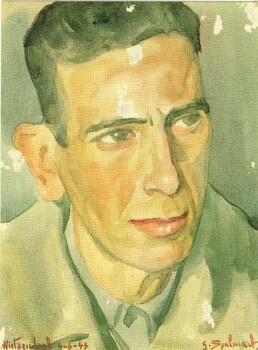

Carlo Lucci was not just any professor. In the chaotic post-1968 our university, in a lively discussion of a faculty council Giovanni Klaus Koenig said he recognized coherence only to two colleagues, and one was Carlo Lucci, who had proved it since 1944 when just to be coherent fell in a prisoner camp in Germany.

On return, he had to start from scratch, and so, after a long period of hardship, he decided to resume relations with his beloved faculty by contacting a former mate who, in the meantime, had made a brilliant career in the Florence University.

– It’s okay to be my assistant – the mate replied – but call me professor.

Frost.

Well, Lucci was not a professor of that mold. It would be limiting to say that he taught design: he taught design ethics. Of his teaching I remember two things above all: the ethical approach to design, seen as a service due to the community, and the critical method, that is, not to be satisfied with the work one is doing but always to be its first inexorable critic.

Just as some archistars do today.

In 2011, in memory of their father, Prof. Lucci’s sons published a text of memories, ‘Lontananze’. Here follows my contribution.

Ricordo di Carlo Lucci

Portrait of Carlo Lucci in captivity

(Gino Spalmach, 1944)

From left: Alessandro Bellini, Maurizio De Marco, me, Carlo Lucci.

The Detained Student

A student of mine ended up in prison for drugs. A large quantity was found hidden under his bed, in the bedroom of a small apartment he shared with other mates. He defended himself by saying that one of them had hidden it there, and that he knew nothing about it, but he was not believed and the sentence was triggered.

In prison he resumed his studies, and one day he applied to the department secretariat to take the exam of Characters of Buildings. Our director asked for the availability of three teachers, even of related matters, and strangely that was not easy. However, the commission was formed, and so one day, after some bureaucratic procedures had been completed, we were able to enter the prison of Sollicciano.

There we met the boy’s father, a man wrapped in a grey overcoat, elderly not so much for his age as for his pain. He had been a school teacher in his hometown in Calabria, and now consumed his time and resources to follow the events of his son and help him on the road to recovery.

We exchanged a few words, and then walked into the room where a bench with some chairs had been set up. The boy presented himself polite and composed, and passed the exam well; if I remember correctly, all three of us commissioners were a little wide in the grade.

For the student, this was the beginning of a hoped-for path to recovery. But above all it was for his father: the gratitude that this man showed me, even after some time, for some signs of encouragement and for having spent some words of confidence and hope, was as great as the heart of many people in the south.

The Everest Top

I read in a book – ‘Into Thin Air,’ by Jon Krakauer – that a young man biked all the way from northern Europe to the Himalayas to climb Everest (obviously, not by bike), but then, warned of incoming bad weather, gave up and turned back. Very, very wise choice, as the frozen bodies of many careless person dot the climbing paths.

This story reminded me of a student named Silla, who, unlike the Roman leader of the same name, was mild-mannered and shy. Silla had come from Mali to study architecture, and got over my exam not standing out, but showing application and good will. It didn’t take long for me to realize that he had made, in his third year of study, a much more arduous journey than any Italian student.

After that I didn’t see him again, but a few years later he came back to ask for his thesis. He told me about his hard life, and that to support himself he worked as a hodman in building yards. He wasn’t a liar, you could see it right away, and his hands testified to it, as did the pencils and scraps of paper he used for his drawings.

Now, there are various types of students and various types of theses, and it is a good idea to choose on a case-by-case basis the theme that seems most suitable for the undergraduate. To Silla I suggested one that was within his reach, both in terms of difficulty and time commitment, and also in terms of cost, considering that a thesis in Architecture can involve a remarkable expense. So, with great effort Silla was able to draw what was strictly necessary, but his sheets of paper made it clear how painful the elaboration of that poor project had been.

On the other hand, in many years as a thesis commission member, I had seen all sorts of events, so I felt I could bring this student to the discussion trusting in the understanding of the commissioners. Silla, like Dorando Petri, arrived at the finish line of his marathon without any more strength.

But unfortunately there was no understanding, not even a hint. Case more unique than rare, Silla was not admitted to the discussion: the president denied the admission not so much for the content of the thesis, but for how it had been presented, and not a single voice was raised to support the student, despite the fact that some professors were known for their ethical and social openings. All lies.

Silla said nothing, not a word; only his eyes said many things, but no one wanted to see them.

Incidentally, that icy president some time later ended up in the newspapers for having stolen a purse in a store: but he had chosen his victim badly, because he was a magistrate who chased him not only up the stairs and into the offices of the University, but then, obviously, into the courtrooms, where he was sentenced.

Of the mild-mannered Malian boy I knew nothing more: after some research on the net, it did not turn out that he had graduated. He probably returned to his homeland without having reached the top of his Everest.

Marrying a Student

– Prof, would you marry me?

After a moment of bewilderment and a few laughs, it was immediately clarified that the matter was celebrating in the Town Hall, Palazzo Vecchio, the wedding of her, a promising architect who had graduated with me a few months before, to a young tutor of the order, on his way to a tough career but highly motivated.

What a beautiful couple those two young people were, two who gave good hope for the future of our troubled country, as I could say for many others – or even all. And what an honor for me: I don’t think there are many professors who can boast of such a proof of affection.

So one day I put on the tricolor sash.

At the ceremony we were all excited and moved: a beautiful day, a beautiful memory.

A few years later, however, the events of life – and the effects of some intrigue – led my two newlyweds to have to stay away from each other: he was sent in the deep south to face the organized underworld and the landings of desperate people, and she had to join the ranks of our graduates who are continuously welcomed by foreign universities. And nine thousand kilometers of distance certainly couldn’t help their marriage.

What a sorrow.

But now they are happy again, and that’s what matters.