Upstairs and Downstairs in the Baptistery

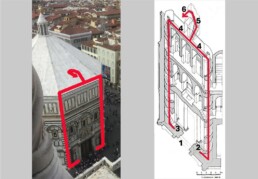

In the florentine Baptistery, on the sides of the Door of Paradise, two spiral stairs lead up to a corridor that, originally, reached a dormer on the roof that was demolished some centuries ago.

Making two stairs to reach a single dormer seem a nonsense, since it was an increase in work and expenses. But the architect certainly considered all that, and decided making two stairs because not looking at some occasional presence, but at the flow of many people, that is the workers who were continuously moving around in the building site to carry out their tasks in any occurrence. Even the scaffolding ladders could serve this purpose, but were exposed to the weather and uneasy in use: an internal stair was certainly preferable, but, being narrow, crossing two men would be a problem, to be solved by making one stair to go up and one down. This was the aim of the two stairs: a faster and smoother work.

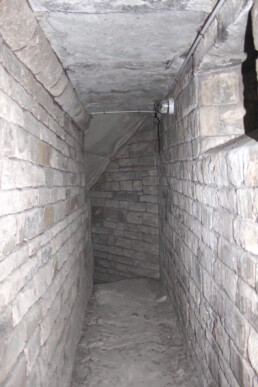

But, in addition to facilitate the workers’ movings, the architect also wanted to make them safe: so he covered the stairs, from ground to top, with a ceiling made of very sturdy stone slabs, carefully and precisely walled in for the aim of protecting anyone on stairs from the possible fall of something from above. By that ceiling we understand that in any moment of the building, while the workers were passing by the stairs, works were continuously carried on above them, and this began just from the lower part of the building because the stairs are covered also there by the ceilings: a management of the works that is undoubtedly original and worthy of further study. In short, the architect thought about the safety of the workers in a context of works that had to proceed without downtime or obstacles. A scenario of notable organization that indicates the activity of an experienced construction company and a project drawn up with great care as referred by the Florentine chronicles: the Baptistery was built by the best builders of the Roman empire.

Of course, the stairs were only for workers, because the materials followed other ways depending on the delivery point and the placement of the cranes; and their use had to be continuous, despite the poor lighting, provided only by a few slits on the outside and by the openings towards the corridors of the gallery and the attic. Indeed, no torch holders or smoke spots are seen on the walls: probably torches were not used because unpratical, having the hands full and given the brevity of the walks. Anyway, to avoid tripping, great care was taken to ensure the regularity of the steps, which are very well worked even in the crossing points.

A final note about the great fancy used by some scholars to explain why some doors were opened in the facades at various heights and positions, and then closed and covered by the marble claddings. According to them these doors led to loggias, of which obviously no presence can be imagined or found in the perfect drawings of the facades, or to raised paths to connect the Baptistery to the bishop’s palace in order to get the safety of the clergy, subject to popular violence if they had to walk on the ground; forgetting that in all construction sites of all times, temporary passages are made during the work between the external and internal scaffolding for obvious practical reasons; passages that are then closed when they are no longer useful.

Staircase outline: 1) Gate of Paradise; 2 and 3) stairway accesses; 4) attic corridor; 5) ramp to the original dormer; 6) original roof exit (elaboration based on a drawing by Prisca Giovannini).

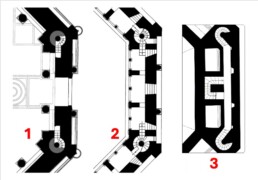

Plans of the stairs on the ground floor (1), the gallery (2) and of the corridor in the loft (3).

When in Florence Greek Was Spoken - 2

(follows from part 1)

III – V Century Soldiers

Soldiers from the East

As we know, Davidsohn attributed to the Syrian community in large part the spread of Christianity in Florence, considering Christians a small nucleus at the time of Ambrose, but his explanation was based mostly on the assumption that the Eastern commercial communities constituted then the main migratory movement, but forgetting the much more important one of the military: the transfer of troops from the East for the aim of defense in the West was in fact intense and continuous. The presence of these soldiers is documented in many places where defenses against the barbarians were set up, especially in northern Italy, and very likely that also happened in Florence. In the Santa Felicita graveyard several tombstones were found of soldiers of the garrison perhaps died in service, or of veterans settled here because of property or family ties.

This presence of troops must have lasted for a long time, also given that the military condition was hereditary, so it is possible that over time the ties between the local population and the military have become closer, even involving the religious sphere. The same use of the Greek language can be well explained in a military context: for troops coming from various areas of the Pars Orientis of the empire a common language was necessary, also given that the contingents were frequently integrated or alternated: it was therefore logical that in the corps the use of an international language such as Greek was maintained.

The presence of soldiers therefore explains much better than the weak commercial contacts hypothesized by Davidsohn the local diffusion of Christianity, which would have occurred both due to the integration generated over time between the stationary soldiers and the civilians, and to the presence of missionaries following the troops. This presence is documented for the seventh century, but it is possible that an oriental clergy followed the troops as early as the fifth century, in the wake of those relationships which, on the religious level, were posed as we have seen between Florence and the ‘Greek’ world since the time of Ambrose.

Military Gravestones

Even the dates on the tombstones of Santa Felicita suggest to deepen the idea of the military presence. The explicitly military tombstones do not have dates, except one, and are written in Latin. Some other tombstones suggest a probable belonging to soldiers due to considerations that will be set out below.

So: over all the tombstones found, both Latin and Greek, eight have dates between 405 and 547, almost a century and a half. Inscriptions with dates are most frequent at the beginning and end of the period; in the intermediate years there is only one stone, dated 491. Therefore it seems that the cemetery was used more in the early 5th century and in the middle of the 6th, i.e. the times of the invasions of Alaric and Radagaisus and of the Gotho-Byzantine war.

Four tombstones are of barbarian soldiers as the names indicate. One, rather late, is of Macrobius, ‘primicerius Primi Theodosianorum Numeri’, i.e. commander of a unit of the First Theodosians, who died in 547, therefore during the Gotho-Byzantine war. The Numbers, as the Cohortes and the Alae, were auxiliary troops of the late empire, formed by barbarians and placed to defend the borders, especially in the western provinces. Macrobius was to serve in those contingents that the Byzantines transferred to upper Italy in the years between 537 and 568 during the war against the Goths. The other three, which unfortunately have no date of burial, belong to soldiers of a particular corps, the Schola Gentilium, which, as the name indicates, was made up of barbarians; and names of barbarians had precisely Mundilo, who died about 40 years old, Segetius, who died at 38, and Pylades, ducinarius, i.e. commander of a unit of fifteen men. To reinforce the indications regarding the presence of this selected body in Florence, a fragment of a tombstone found in 1948 also contained the indication of a schola. Another tombstone, that of Anastasius Galata, is probably to be attributed to a Byzantine soldier who was also a barbarian, given its origin from Galatia, a region famous for its valiant warriors; and, as I have already mentioned, Theoteknos himself buried in 405 could be an Eastern soldier, although his tombstone offers no indication of this.

Comitatenses and Limitanei. The Scholae

Even an historical overview confirms the presence in Florence of soldiers from the East. At the time, the imperial army was divided into Limitanei – troops stationed on the borders – and Comitatenses – troops of the field army – divided into actual Comitatenses and Palatini, stationed in the imperial palace. The Limitanei, already starting from the fourth century, and then especially from the fifth, were inefficient, sedentary bodies and devoted more to the cultivation of the fields than to military exercises, which therefore constituted the permanent part of the army, placed to defend the borders in permanent garrisons. The comitatenses were instead the mobile part of the army; however over time they too were dispersed into regional armies, becoming pseudocomitatenses, and this seems to be the case in Florence. The defense of the Arno pass was the logical consequence of the dangerous situation in which all the cities on the possible routes of an invasion found themselves. To head towards Rome, the barbarians who descended from the north-east of the Po valley could choose whether to follow a route along the Adriatic, or whether to cross the Apennines, reach Tuscia and then head to Arezzo and Rome. In this case it was very probable that an invader would choose the road to Florence, and this can explain the presence in the city of troops normally stationed elsewhere and whose ranks were largely made up of barbarians, given that the recruitment of barbarians was then a common practice.

Reinforcements from the East in the Early 5th Century: a Permanent Defense

On various occasions, already starting from the years preceding the invasion of Radagaisus, many arrivals of soldiers from the East improved the defense of Italy in the context of a great effort. At that time, in fact, the empire, although divided into two parts, was still considered as one, and the movements of troops within its borders fit into a broad and well-established picture: in the early years of the fifth century, troops sending from the East was requested several times by Stilicho, Honorius and Constantius.

Looking ahead at the danger of invasions, between the end of the 4th and the beginning of the 5th century many cities of northern Italy, and Rome also, reinforced their defences. The danger became actual in 401 with the first attempts by Alaric and Radagaisus, so the following years must have been lived in Florence in a climate of great tension, until in 406 there was the liberating intervention of Stilicho; and the fact that in the subsequent invasion of 408 Alaric did not pass through the Florentine territory indirectly suggests that Florence still had its defenses intact.

Therefore the presence of soldiers in Florence must not have been an episodic event linked to the invasion of Radagaisus. A city garrison must have already been present and continuously supplemented with new shipments of troops: in fact, there are abundant testimonies of recalls made in emergency conditions, and slaves were drafted too. In this context, the presence of soldiers of barbarian origin in Florence can be explained precisely by belonging to the garrison or sending of reinforcements troops.

The soldiers buried in Santa Felicita’s graveyard could therefore have been transferred here to deal with an emergency situation that continued over time (a particular form of chain migration, in short), and probably their presence was not linked to an exceptional event, such as was the invasion of Radagaisus, but to a program of reinforcement of the defenses implemented on a large scale, began before 406 and lasted for a long time. These soldiers must have belonged to a garrison stationed in the city and reinforced at the beginning of the 5th century with the dispatch of troops from the eastern provinces, as evidenced by the origin of the deceased (Cele-Syria, Galatia), their language and the same religion; troops who remained stationed in the city integrating with the local population, as evidenced by the fact that the dead soldiers were buried in the cemetery of the local Christian community.

On Mundilo’s tombstone is written ‘sen. sco. gent.’: a veteran, therefore, of the Schola Gentilium Seniorum, troops that originally belonged to the comitatus, the emperor’s guard, and followed him on campaigns. Then, from the fifth century, the emperors no longer took the field in person, and this would make the three tombstones of Santa Felicita date no earlier than the beginning of that century. Perhaps even Theoteknos, although died in 405 and therefore almost a century and a half before Macrobius, could have been a soldier engaged in the defense of Florence, already then threatened by invasions.

A garrison must have already been stationed in the city just at the end of the fourth century, given the worsening of the situation, and that its consistency was not suitable to face the danger that was ahead is demonstrated by the fact that Stilicho, in the moment of crisis, had to resort to quite extraordinary initiatives in order to have the soldiers he needed in time in Florence.

In addition to the call for reinforcements, the city faced the threat by doubling the circuit of the walls on the north side: this is revealed by the trend of the ancient streets in this area and by the characteristics of the finds – walls, towers, gate – unearthed in the excavations of the late nineteenth century in Piazza San Giovanni. This partial doubling of the walls – a usual defensive expedient – was a work of great commitment carried out in an emergency situation, for which all available manpower must have been used, even calling it from outside. In short, there were the preconditions for increasing the migratory flows from Syria, where, among other things, not only trade and crops were developing at the time, but also craft activities in the building sector, for which the easy finding of capable workers had to be proposed .

Trade and Army Networks

The presence of a garrison must have brought to Florence not only merchants and traffickers, but also missionaries and priests of various cults, given that the military were very attached to their devotions. In such a context it was inevitable that the daily attendance between the families of the residents and those of the garrison soldiers, as well as with the various characters in tow, would create ties, and that these ties would also extend to the religious sphere. The evangelization of the Florentines must have occurred not only through indoctrination, but also with custom, examples, mutuality, that is, along the same paths of the trade networks: a concept that should be adapted to ‘trade and army’ networks.

Thus we have a much more convincing explanation than that of the hypothesized merchants who, if resident, should have made the local language their own for obvious reasons linked both to their own activity and to the custom of relationships established over time. These groups of ‘Greeks’ present on several occasions in Florence in the years between the fourth and fifth centuries must have constituted a presence established in the territory and in the local social context according to models that – mutatis mutandis – we still find today, for example, in the military bases present in Italy but belonging to allied countries: within them the laws, customs and language of the country of origin are maintained.

The Borough of the Greeks

And finally: since the stay in Florence of the builders of the Temple must have lasted for about twenty years, considering that together with the workers, family members also had to find hospitality in the city, we can think that this is the origin of the Florentine Borgo dei Greci (Borough of the Greeks), which still maintains a toponymic trace. In Florence, that is, the immigration of workers involved in the construction of the Temple and their families, would have caused an increase in the demand for lodgings at the beginning of the 5th century. Where could this demand be satisfied? Given that the northern, western and southern areas of the town were not suitable for building due to the courses of the Arno and Mugnone, and in the southern area also due to the existence of the cemetery in the Oltrarno, an expansion could mainly involve the area east, that of the amphitheater, where there were spaces, roads and waterways. It is therefore presumable that buildings have arisen along the suburban road towards Arezzo over time, as always happens near the entrance to a city, and just to satisfy the new immigration: something similar to what occurred when Florence was the Italian capital and many employees of the ministries arrived from Turin. Currently the Borgo dei Greci is referred to the possessions of the ancient Greci family, mentioned in documents of the XII century and also in the Divine Comedy; but this family itself could have preserved in its name the memory of a far origin from oriental groups.

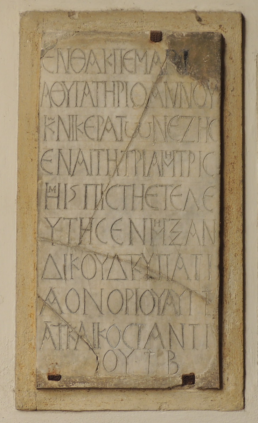

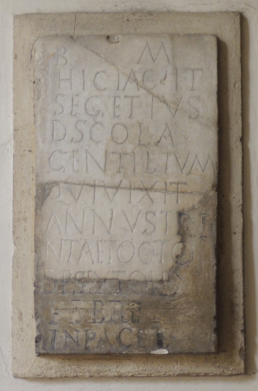

The tombstone of little Mar[cell]a, dated 417 as indicated by the names of the consuls of that year, and that of Segetius, a soldier of the Schola Gentilium.

About Moses' Horns

What does the Baptistery have to do with the famous question of the horns of Michelangelo’s Moses? Nothing, of course, but there’s a reflection on the choices of the artist that I would share with my readers.

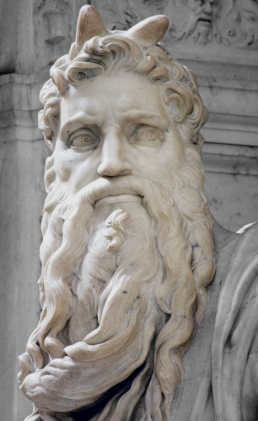

As everybody knows, the Moses of San Pietro in Vincoli has horns on his head, instead of the light rays so frequently depicted that certainly seem more suitable to represent the shine of prophet’s face on coming back from the second meeting with the Lord on the mountain.

But did Moses really have a shining face? On this point, the biblical text (Exodus, 34, 29-35) proposes a difficult interpretation: grossly simplifying the terms of a very complex and obscure question, according to some scholars his face had a terrible appearance, so that, when he realized it, he had to cover himself with a veil.

This uncertainty stems from the hard translation of a key word that in Hebrew can have two readings – ‘karan’ or ‘keren’, that is ‘light’ or ‘horns’ – whose exact meaning must be valued in the context and if it’s to be understood in a literal or translated sense.

But fortunately this thorny problem does not concern us: here we are only trying to understand the reason of Michelangelo’s choice.

Let’s start therefore from the evidence that Michelangelo stuck to the text of the Bible of St. Jerome, and that St. Jerome, between the two possible translations – light rays or horns – chose the horns, writing that Moses, on his return, had a ‘cornuta facies’, a ‘horned face’.

Michelangelo undoubtedly would have no difficulty in modeling radiant and luminous shapes, and a head with rays represented a very common iconography. Finding instead a suitable form to connote a ‘horned facies’ for a prophet without using the special effects we see today, but having instead to model it in a solid and fully convincing form, was a really difficult task.

What horns to represent? Think to any horned species of the animal kingdom, from snails to deer, and you can realize that Michelangelo was as squeezed in a corner. Anyway, he had to mold horns, which would have had a value of symbols; and symbols of this type could offer to malevolent observers easy opportunities to create embarrassment to Christians, Jews and the pope himself.

But he avoided any veiled or even distant reference to a threatening, ironic or even less demonic sense by choosing the least offensive horns: two horns just sprouted, like those of the little goats he saw grazing in the meadows of his Casentino as a boy.

Could he not choose horns? No, since he knew the Holy Scriptures very well, and had not to seem an ignorant, but also because for him sticking to the official text approved by the Church was unavoidable, given that he was working for the pope and that in the occasion he certainly had an expert biblical scholar at his side. Therefore, any possible objection on this point would not have been consistent.

But it could be also have been necessary to face some bad faith criticisms; and in this case I believe – it is only a conjecture of mine, of course – that Michelangelo could also counter them by pointing out a valid argument, i.e. that horns were an appropriate symbol for the leader of a people to conquer a new land.

Let me explain why, starting a bit far away but making the shortest path.

In the circles of Renaissance intellectuals, the myth of the Roman god of the borders, Terminus, was known. In ancient Rome, to move the boundary of a field or a property secretly or without the neighbor’s permission was a major crime to be punished very severely.

But then someone pointed out a quibble: after all, the conquest wars that the Roman people made to the whole world what were they but unauthorized displacements of boundaries? Perhaps the Roman state preached well and raced badly?

In the homeland of law, in short, an embarrassing question was posed.

Then, to get a face-saving, the Romans found a ploy that was a masterpiece of hypocrisy. According to it, they established that when a commander (dux) was appointed to a military expedition, during his performance he became the god of the borders himself, Terminus – the strange god who, as someone perhaps remembers, had a symbolic relationship with the construction of the Baptistery. Therefore, as long as he was on his duty, the dux had the divine power to move the state boundaries, that is, to annex the conquered territories, because the gods of Rome had guaranteed to the Romans the conquest of the whole world.

So, the dux would temporarily become the instrument of this divine plan becoming Terminus; and since Terminus was represented as a boundary pole with the head shaped as a fork, also from the dux head two horns were expected to sprout out; and as it was obviously impossible, they remedied by putting on his head, in ceremonies and triumphs, an oak crown to hid them, and everyone pretended to believe it.

Michelangelo therefore could find an answer even to the malicious objections by referring to classical traditions; and in this regard it seems significant that his Moses’ horns are clearly spreading out like a fork, differently from the normal horns on the skull of goats.

When in Florence Greek was Spoken – 1

This text is about a research I started many years ago and still haven’t finished. Indeed, it is probably impossible to finish it because it is very complicated and the available data is very uncertain and incomplete. But the argument is suggestive: I therefore ask for patience and understanding. Thanks.

When in Florence Greek was Spoken – Part 1

Syrian merchants, Byzantine missionaries, Barbarian soldiers. And the Florentines

A Brief Premise:

When Florence was called Florentia, Florentines spoke Latin, but not all of them did: in fact, for a long time, groups of Greek speaking people lived in the city. They were immigrants from the Middle East: businessmen, soldiers, men of the church, they were all people who played an important role in the difficult moments in the history of the city. Some traces of their presence remain to us in a few sepulchral stones from the fifth century which were found by excavating under the Church of Santa Felicita, near the Ponte Vecchio, as well as a few less direct testimonials. A few stories about the city’s church in fact, lead us to suppose that, from the seventh century onwards, there was a Middle Eastern ministry present in Florence that brought worship practices from their homelands to the banks of the Arno. When we expand our vision and see the big picture, it seems that these presences were bound together by a continuity over time which fits in with the general phenomenon that saw many people follow a path that, crossing the Mediterranean, brought the Middle East not only to Florence, which interests us here in particular, but to other places whose coasts overlook the mare nostrum; a path that was tread many times, with different aims and in different circumstances, and it is significant that those people came from the same geographical area and that they didn’t express themselves in their mother tongue, but rather in the international language of the time: namely, Greek.

Three groups of “Greeks”: merchants, soldiers, missionaries

The first group of these “Greeks” examined here is the one we have the most direct testimonies of, and whose presence in the city gave rise to the idea of their important role in the evangelization of the ancient Florentines, even though they were – at least it is believed that – simply merchants. A theory which I think is only partly true.

The second group is comprised of soldiers: we even have some stones left from them that document both their presence in the city at the time of the war between the Goths and the Byzantines in the sixth century as well as their Middle Eastern origins.

The third group is comprised of men of the church, who were also Middle Eastern but spoke Greek and came to the city in small numbers at first but in time became part of a missionary movement that under the Lombards concerned not only Italy: a movement that has remained poorly understood, but whose traces are rediscovered in Florence in the eleventh century, when the Greek prayers and rituals those priests had brought were definitively abandoned.

Formulation and Limitations of the Research

In this text I will seek to interpret the few data that we have in accordance with a rational perspective, even if it is inevitably influenced by a subjective interpretation of the few data points available, for which it is inevitable that there be margins more or less open to interpret that data differently. It should be taken into account, however, that many of today’s more diffuse publications stem from studies, whose bases for the arguments that we are talking about here, were laid long ago, but those bases do not always turn out to be solid, which is easy to test. This will be accounted for case by case in these pages, so that the reader can make their own opinion.

Last but not least, why Santa Felicita?

The last section of the text talks about the cult of Santa Felicita and the story of the church dedicated to her that would be, according to some, the first one constructed in Florence. That is certainly inaccurate, since San Lorenzo was the first Florentine church, but Santa Felicita is certainly among the oldest and the cult of the saint is certainly older, which presents some intriguing elements, given that two saints exist with this name and that the one venerated in Florence (in addition to other saints) is connected to the very unique cult of her martyred sons, the seven Maccabees. The continuous presence of this church and this worship, projected on the background of the city, can shed some light on some very dark times. A bit of light, even if it is weak, indirect, or reflected is still better than darkness, and it can help to correct some errors that are read here and there in texts on the local history, which often get repeated only because they took the information unquestioningly.

(To be continued in the following…)

Allegato

The spaces below the Church of Santa Felicita, where the remains mentioned in the text were found (photo by M.C. Lombardi Francois).