Project and Worksite: the Case of the Nervi Stadium in Florence

So, the Municipality of Florence decided to restore and update Pier Luigi Nervi’s old city stadium, a masterpiece of twentieth-century architecture, and the competition was won by the Arup studio. To carry out the winning project, however, the worksite will necessarly spread over the whole stadium for two years, barring unforeseen events; therefore in these two years the city’s football team, Fiorentina, should play championships and cups in another venue.

Anyone can easily imagine the problems that will arise from that for audience, athletes, staff, police, and the consequent direct or indirect expenses, the logistical, sporting, administrative troubles, the lengthening of times, the lack of incomes. And even the difficulty in finding a suitable venue, a task so hard that the Municipality is attempting to create or adapt another temporary stadium: an expense that will obviously be borne by public finances, and which difficultly will be accepted by the citizens who pay taxes since the Fiorentina owners some time ago offered to build a new stadium with their own funds. An opportunity inexplicably dropped, it is not clear why.

Could this disaster be avoided?

As far as the worksite is concerned, yes, if a few words had been written in the tender notice, such as:

“Will be a preferential element in the projects evaluation the demonstration that the building activities will not hinder the continuity of use of the stadium, minimizing times and discomforts for users, and optimizing sporting use and seating capacity.”

Therefore, without setting any limitations to the creative freedom of the competitors, a different project could have been developed in the way to avoid problems and expenses if similar few words were written. But they were not.

Ouch ouch ouch.

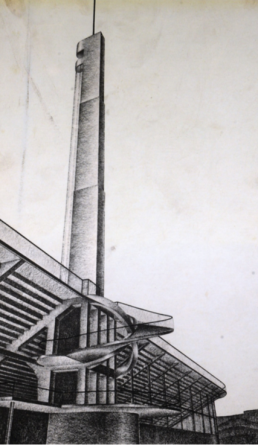

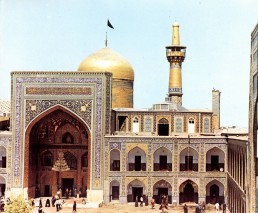

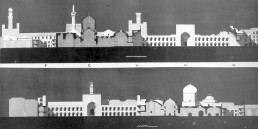

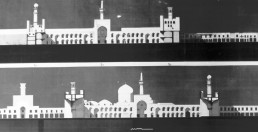

Views of the Arup project for the Nervi’s stadium in Florence.

Below: a study for the roofing of the Nervi stadium in Florence achievable with partial construction sites (degree thesis by Francesca Mirri and Letizia Di Marzo, 2002).

To Protect a Modern Monument: the Nervi's Stadium Case in Florence

To be fitted to modern standards, the Franchi stadium in Florence needs from along time to cover the bleachers, bring the public of the curves closer to the play field, and add the accessory functions today required for an international level plant. Thus, in recent times, the Fiorentina soccer club solicitations have led the City Administration to face a difficult situation due to the problems of protecting the monument. As known, indeed, the work of Pier Luigi Nervi is an undisputed masterpiece of modern architecture, in particular for its famous curved staircases, the Marathon tower and the shelter of the grandstand.

To solve this thorny issue, in which is even on sight the club exodus to another municipality, Mayor Nardella set up an international competition whose results however don’t seem to gain a general consent: there are many negative judgments, expressed not only by the hard to please Florentines, polemists as usual, but also by very balanced and qualified people, whose opinions cannot be dismissed as unmotivated or preconceived. Something really seems to be going wrong on this way, and Florence, after having lost Michelucci’s Station image, cannot afford to burn out another of the very few 20th century architecture masterpieces that the city can still boast of (in addition to these, Fagnoni’s Air Warfare School and Mazzoni’s Railways Power Plant).

The issue is therefore serious, and the administration cannot make an ostrich policy by hiding behind the reports of the contest: we might hear something as “operation successful, but patient dead”.

In order to look at this tricky situation in a constructive key, we must first of all remember that in the initial step of such competitions only outline ideas are presented, and that these ideas will be defined without distortions in the subsequent executive project. So, I’ll make now some personal remarks, even if some topics are difficult to explain by words only, because when talking about architecture we should draw, as when talking about music we have to play.

The most distinguish element in the Arup project is the roof, which, in order not to touch Nervi’s structures nor to stand out in the panorama, has been conceived (I’m quoting the project card) as “a thin rectangular metal blade [that] levitates above the historical stands of the Stadium”. This description appears to be a bit tinged with optimism, given that inside smooth metal sheaths are hidden structures of steel trusses that can cover more than 8 acres (soccer field excluded) at a height of 82 ft (Nervi is at 62), resist to winds, snow, accidental loads and terrorist attacks, and support 160 ft overhangs, photovoltaic panels, lighting systems, maintenance walkways, and even two long stands with skyboxes hanging down from it on the Marathon side.

It will be interesting to see what modifications will be made to this structures in order to adapt it to the anti-seismic and safety current rules; and to avoid complications or delays in the programs, it could be extremely useful for the Municipality a timely confrontation with the Civil Engineering and the Fire Departments, which do not seem involved in the preliminary steps of the competition.

But the protection of the monument is not matter of standards and measures only. From a perceptual point of view, this plate will not seem levitating, but looming over the stadium. The Franchi (before ‘Berta’) is born as a dilated proportions space, wide and open, with the view of Fiesole and the hills, and the tower of Maratona soaring into the sky, and the character of a space is also a value to be protected, as was evident to everyone watching, for example, some recent artistic performances in Piazza della Signoria. But in the Arup project (and not only in it) Nervi’s space is no longer found, even if its main elements – tower, stairs, shelter – still remained there: an image of exteriors became an image of interiors, and a rather cold one.

And in front of the objection that it was impossible to do otherwise, since the two new transversal grandstands would close the perimeter all around the soccer field, the answer is no: maintaining a visual relationship with the landscape references was possible if other types of roofing were designed. In order to innovate the monument while respecting it, in short, there was a narrow but practicable way to follow, named measure and essentiality, that is the Nervi way. He with few resources created essential but very iconic structures, well knowing that ‘genuine’ structures are beautiful, and have to be shown.

The Arup project offers matter for reflection also on other topics concerning the protection of architecture, but here, in order not to generate misunderstandings, it is necessary first of all to clarify that adjustments are necessary also for monuments, to avoid that their functionality may be lost, because a building without functionality dies, and what was architecture becomes archaeology. For these adjustments, no imitation of what already exists is suitable: it is necessary to create, to innovate, but humbly and respectfully, in a way balanced and coherent with the values to be protected, and this way consists essentially in using an appropriate architectural language, whose words are geometries, proportions, calibrated materials, and, precisely, also a sense of measure, so that the new image does not obscure the one to be protected. And here it is clear that, beyond the legitimate diversity of forms, Arup and Nervi do not speak the same language.

Was it possible to make a roof that didn’t overpower the image of Nervi? Yes, all the way: today many stadiums have beautiful lightweight roofs, made with new materials that offer incredible and innovative possibilities, and also in respect of the environment. Structures of this type, responding in substance to Nervi’s lesson, could allow to maintain that sense of open air that characterizes the stadium and to give oxygen to the tower, the canopy, the stairs – that not by chance are round. From what I could see, however, no one followed this track, perhaps fearing that lightness and minimalism would not be appreciated. And yet the ancient builders had pointed out this solution: “Et vela erunt” we read on the walls of Pompeii, that is ‘Come people to the amphitheater, today we’re going to pull up the veils, no sunburns!’. So here’s the suggestion: light, mobile covers, en plein air, as also on the Colosseum. Two thousand years ago.

But in the end I would add a note of great bitterness about another type of protection. In the contest call there was no suggest about maintaining a respectful remembrance, as there still is, of the five young men shot at the stadium wall in ’44. Why?

That strikes me as a very bad signal, and Arup has nothing to do with it.

Right: drawings of the Marathon tower with the helicoidal staircase and of the covered tribune (1930; Florence Municipality, documentation of the competition announcement); example of Eclipse membrane roofing; retractable roofing of the Olympic Stadium in Rome; testimony of Luigi Bocci in: M. Piccardi and C. Romagnoli, Campo di Marte, La casa Usher, 1990.

The doormat affair

In Italy, around the 1980s, housing cooperatives were a significant source of work for architects and engineers. There were various kinds of cooperatives, large or small, Catholic or Communist oriented, structured as ministries or simply do-it-yourself, scheming or fair. In Florence there was one properly managed, led by members dedicated to the common good and nothing else. Just nothing else.

After having overcame many bureaucratic and administrative hurdles, that cooperative could sign the housing contract of for its many members with a builder not well known which submitted an offer a few lower than another of a builder from long since serious and reliable. A little difference that the cooperative’s board could easily ignore – but fairness prevailed.

So the work began and that builder had a great satisfaction, also because he received the payments of his bills immediately, just when issued. Unbelievable stuff.

But…

But one night someone enters the building site and devastates scaffoldings, formworks, props. Chaos everywhere. What is it? Intimidation? Threats? Warnings?

Headlines in the newspapers: mafia in a construction site.

Nothing of that; only workers who didn’t receive a penny of what had been paid by the cooperative and cashed by the builder.

Perhaps also a chance event made someone very enraged.

On a beautiful spring Sunday, the Formula 1 Grand Prix of Monte Carlo was on air in TV. Before the race, the cameras frame panoramic views and the crowd. One camera lingers on the façade of a grand hotel on the seafront, where a figure is leaning out of a balcony waving bye-bye. Yes, it’s he, the builder himself, and says hello from Monte Carlo.

That was probably the straw that broke the camel’s back.

Legal issues that arose between this gentleman and his workers could involve the cooperators, dangerously delaying the delivery of their houses. Months of great tension followed: the work should not slow down, we had to get the goal. Every act, every uncertainty, every request, could lead to delays, increased costs, litigations, perhaps even the seizure of the site: unimaginable consequences.

But as God would, the housing was delivered, albeit with some minor delays and consequences, the assignments were done, the partners’ families took possession of their houses and the condominium was set.

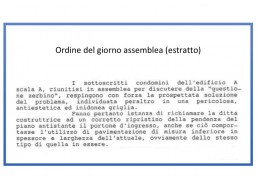

The first assembly had only one point to discuss: when raining, some water remained in the external dimple that contained the doormat, so was necessary to find a solution.

Agenda: “The doormat issue”.

I put that in a frame.

If Calling…

‘Se telefonando’…

I always enjoy listening to this old Mina song, also because I associate it with an adventure.

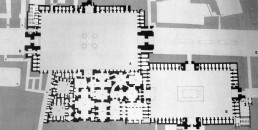

Not a few years ago, my friend R. asked me if I would help him take over a religious complex in a distant city in the Middle East, for a study that interested a local professor with whom he was in contact. We agreed, planned what we could and left loaded with various instruments. Since we both had school commitments, we agreed that the work would be done during the summer vacations: a month or so to spend in a place that was totally unknown to us. And I emphasize totally: the informations available, since there was no Internet, were in fact very scarce, but I remember very well the note that concluded the brief description provided by a Hachette guide: “For their own safety, Western visitors are advised not to approach the monument”.

Something worrying was on the horizon, but the die was cast and we left.

So, after hours of flying and a very long journey through picturesque but desolate places, on a rickety bus in close contact with a varied humanity, we arrived at the site and discovered that there was not a free hotel room in the entire city. Various instructive experiences followed, but in the end our very authoritative principals dislodged the legitimate occupants of a room in the city’s main hotel, and so we were able to settle in.

Although we had a special pass and could rely on the help of a young and willing engineer, it was soon evident that we had committed ourselves to something impossible. Not only was the place frequented by multitudes of people with whom, confirming the guide’s warning, it was inadvisable to relate to, given our evident extraneousness to the cults they practiced, but the monument itself proposed difficulties that we could not overcome. In fact, it was not a building, but an urban complex that occupied an area as large as 15 soccer fields, and even if we took away houses, stores, hospices, shelters, religious schools, markets and whatever else, there remained a monumental part that was more or less equivalent to four or five Pitti Palaces.

Let’s add that the terrifying heat, the suspicious overseers and the people animated by religious ardor that swarmed everywhere complicated even the simplest operations. For example: when we unrolled a metric tape to try a measure, the faithful would take possession of it and kiss it with devotion as if it had been an extra large rosary.

I believe that the face of the captain of the Titanic when he saw in the darkness of the night the glow of the fatal iceberg approaching, gradually assumed the same expression that formed on our sweaty faces when we became fully aware of the fact that whatever effort we had made, whatever subterfuge we had devised, the result could only be one: disaster.

In the darkness of despair, however, a faint and distant flame flickered: we still had a chance, albeit an unlikely one. The great and secular monument, like all self-respecting great and secular monuments, had at its service a legion of masons and decorators who provided uninterruptedly for its maintenance, and they reported to a technical office. Was it possible that in the technical office there was no relief?

As our iceberg, in the form of the month’s deadline, was approaching, we attempted a reckless move: to contact the chief engineer of the maintenance office to see if we could get some help from him. So we invited him to dinner and started telling him the usual stories about the beauties of Florence, the Brunelleschi’s dome and so on.

He was very kind: he didn’t know a damn thing about Florence, but he knew very well who we were and what we had come to do, and above all he immediately guessed where we wanted to go with all our chatters. And it was logical that he didn’t like the fact that his competences had been bypassed: we came in his domain to do things he was responsible for, without him having any say in the matter, nor any recognition or advantage. Unacceptable.

But the rules of good manners had to be respected, and he respected them by inviting us in turn to visit the monument. One fine morning he led us all over to see a lot of interesting things, but for us the most interesting of all had to be in his office: if any survey existed, it had to be there, and we couldn’t miss any possible opportunity.

So, when we returned from our tour and the engineer had us sit down in a small sober room that overlooked a wide cloister, as soon as we entered our eyes ran to scan everything for traces of reliefs, but on the walls there were only religious pictures and souvenir photos, on the shelves the folders of files and some books, and the desk was sadly empty.

So nothing, zero, the end.

The Outlaw Balcony

In an apartment in the old center of a beautiful city lived a family that had a big problem, because the little daughter, due to her disability, was forced to spend the days always at home. Of the outside world, apart from the usual trivialities of TV and a few outings when necessary, she knew practically only what she could peek through the window, which overlooked a busy street and from which you could glimpse the corner of a tree-lined square, always animated and lively.

One day, the father thought that a balcony would allow his daughter to feel a bit of that life, almost if going out and meet someone. He turned therefore to a technician, but was disappointed: the municipal rules did not provide for changes to the facades of ancient buildings in that area. But he did not give up: he applied to the Municipality to expose his problem and on an appointed day he was received by the Building Commission.

Faced with the human case, the Commission did not feel like rejecting the request, as it would have been inevitable by applying the rules literally. In the end they decided to propose an exception for the case, but with precise conditions: medical certification, an aesthetically suitable project and finally the commitment to restore, registered with a notarial deed, when the necessity would cease.

Managers, councillors, the mayor, no one objected, and so permission was granted, the balcony was built and the little girl could spend some quiet hours there.

In the wake of this happy experience, some time later was also resolved the case of a disabled person who lived on the outskirts of the same city, in a hovel whose tiny bathroom was located halfway up the stairs, and he had to climb to it by force of his arms; so he was allowed a small extension on the ground floor, occupying a few square meters in his courtyard to build a toilet.

In short, everything was fine: technicians and administrators had listened to what common sense (and the heart) suggested, undoubtedly forcing the rules, but with the utmost transparency and setting precise conditions for small exceptions. I believe, however, that today all this would not have been possible with the on line procedures that progress has imposed for building practices, and not only for them.

Rural Traps

Once upon a time, somewhere in the flat west of Florence, there was a large abandoned farmhouse, once beautiful and valuable but now ruined and invaded by brambles and brushwood.

One day someone buys those ruins and commissions a young technician to carry out the rebuilding. A complex job, so the young technician prudently presents a draft of what he’s conceiving to the municipality in advance to find out if it is feasible. The answer is ok, but beware: the existing ruins must be maintained and can only be integrated where necessary. In other words: you can’t tear down everything and rebuild. Is that clear? Yes, it’s clear, goodbye.

Works begins, some time passes. Then, one day, a police report lands on the desk of the town planning officer: in a casual survey was discovered that all the walls had been razed down and completely rebuilt, absolutely the whole. Exactly what should not have been done.

Tsk tsk…

Result: hefty fine (many hundreds of thousands of euros); order to demolish the new building because completely non-compliant (many more hundreds of thousands of euros); impossibility to build again the pre-existing volume since the demolition caused the lost of all rights on the area, now only provided as rural use in the City Master Plan in a hydrogeological constraint (further hundreds of thousands of euros of damage); devastating legal struggles (some more pennies)…

From the construction site, a bureaucratic and legal shock wave of the utmost intensity spread to offices, professional studios and courtrooms. A devastating war breaks out: the owners have to pay, but they claim against the builders and the technician. The builders, with specious arguments, call themselves out, saying in short that they obeyed what ordered. The spotlight shift to the young technician, probablely the least responsible for the disaster: in fact, the company had most convenience in rebuilding everything completely, and so the owners because the work would have been faster and the costs much lower. They were probably both confident that the place was out of the way and that, if everything was done quickly, nobody would notice anything. But instead…

So the young technician, who probably faced a fait accompli and did not protect himself in advance in any way, was lost.

Perhaps he could quickly reach Patagonia.

Postilla

It is never a good idea to defy the law thinking you can get away with it because you think the odds are in your favor. Here’s another experience.

Years ago, a young couple, in order to escape the city, bought an old abandoned farmhouse. The place is definitely off the beaten paths, in the middle of a wood and reachable only by a path that is moreover interrupted by a landslide that formed a large pool.

Works begin. Next to the house there is a small outbuilding where you can barely stand. The owners ask the architect:

– Could we raise it a little?

– Impossible: it’s not allowed.

– Don’t be fussy: who could see? We’re out of this world here.

The request is repeated. Finally, the architect is about to give in.

But just a little before the fatal step, one morning, among the trees of that remote wood, silent presences materialize. Gentlemen approached the house with measured but firm steps and introduced themselves:

– Good morning, I am the mayor, we are planning officers, I am the chief of the technical office, I command the urban police, I represent the forestry, and so on.

Surely that morning nobody was sitting in the Municipality.

– What are you doing? Show us your licenses please. Well, let’s see…

– All right, goodbye.

– Just a moment, please!

From the owners’ and the architect’s mouths some rather disjointed words erupted, that in substance meant a question:

– What the hell are you doing down here? Are you on the trail of a kidnapping? Is counterterrorism involved? Are you looking for drug refineries?

– No, we’re checking out all the springs of the municipal water supply, and since we were passing near here….

Bingo.

A Dudok's Hydrophany

On an August afternoon many years ago, I went to Hilversum to see its famous Town Hall, Dudok’s masterpiece.

Willem Marinus Dudok, the greatest exponent of Dutch neo-plasticism and a follower of Wright, had studied as an engineer in a military academy, then became chief architect of that city, leaving behind exemplary works which inspired, among others, Michelucci and the Tuscan Group for the most beautiful parts of the Florence Railway Station.

The place is quiet and silent, and very green. In a very large pool of water on the front of the City Hall the sky and the architecture are reflected in a typically Dutch luminosity. I walk along the pool, I pass through a long arcade that looks like a modern stoà, arrive at the entrance and there I stop, thinking that I should ask someone for permission to visit. But there is no one. A little embarrassed, I cautiously walk in: very clean spaces, of a sober and accurate elegance, where every detail is a lesson in architecture.

On the right, the main staircase invites me to go up. I come to a vestibule, beyond which I imagine the Council Chamber must be located. Given the absolute silence, I venture to open a door: I see a large deserted room, with all the furnishings in place, an elegant space where everything is still, and even time seems to pause.

But to the right there is something that pulses: it’s the reflections of the outdoor pool that are projected on the wall behind the seats of the council, drawing a lively and iridescent dance. That play of light animates the whole space, and I try to imagine it when it shows up during some council meeting: the effect must be really nice.

For me, in that moment, the effect is to drag my thoughts far away: water, earth, light, time… I think of the flowing waters that shape the landscapes, of the ancients who used water to measure the hours, of the admirable hydraulic works of these ‘low lands’, and then of the light of their immense sky crossed by clouds, the same sky of Ruisdael’s landscapes… Holland, land stolen from the sea, surprises you by making you feel everywhere in contact with the primary elements of Creation, even here in this composed and silent council room.

A long time later, leafing through a book on Dudok, I think back to these suggestions and I wonder if Dudok had somehow foreseen that play of reflections. I look at the drawings of the project and find some clues: the pool was brought close to the facade of the City Hall, just under the windows, and there horizontal water jets ripple the surface of the pool, while inside, choosing a transversal arrangement of the seats, and not a longitudinal one as normal, the main wall of the room is brought closer to the windows; and that wall was also left empty of emblems or banners, as it would have been obvious to place on it.

I’m inclined to say yes.

Then it occurs to me that, in the very same years in which the Town Hall was built, the Afsluitdijk was also being constructed, that is the colossal dam on the North Sea made to close the Zuiderzee basin and take new land from the sea. Thirty-two kilometers of granite brought from Sweden, something like a dozen pyramids of Cheops.

It is not rhetorical to say that that was a historic moment in the eternal confrontation of the Dutch people with the waters. And perhaps Dudok, in that context, might have thought of placing a symbol of the Water Element in the city council room of Hilversum, a city so close to those lands reclaimed from the sea. But not just any symbol: a living, breathing symbol, a kind of ‘hydrophany’….

Maybe?

Bribes by Chance

In Renaissance treatises, the figure of the architect is described as having not only technical and cultural qualities, but also moral ones: probity, correctness, prudence and so on. Even then, in short, temptations must have been frequent, and today we all know how things go.

On this subject I would tell a couple of episodes.

One day, Mr. A, who is building the headquarters of his company based on a design by architect B, meets contractor C on the construction site and, while chatting, asks him what he thinks of architect B.

– Bravo, but he is a great fool.

– Why a great fool?

– Because he doesn’t take bribes, but since everyone takes bribes, his clients will surely think that he does too, and he didn’t. Therefore, he is a great fool.

Of course it is not quite true what B thought, and then there are not only the illicit money transfers: often we only face something ethically inappropriate.

In the years of the Italian scandal called Tangentopoli (Bribesville), for example, as Christmas approached, a large building corporation wanted to join to the wishes to the technicians who checked their works to a big public estate with beautiful televisions, very expensive at the time. Even though everyone’s behavior had been fair, the value of the objects embarrassed the recipients, but returning them would have been a rude and unmotivated act: a different solution had to be found. In the end, in order to avoid any misunderstanding, the technicians thanked the corporation, accepted the televisions but decided to turn them over to the Municipality for charity. The only problem was that there was nothing in the municipal administrative net that resembled a ‘Gift Return Office’. So meetings, trips, letters, explanations and a lot of wasted time followed, until finally someone found a ramshackle social club and a remote poor’s hospice that had recently been visited by thieves.

So everyone was happy. Except for the national public broadcasting company, which sent reminders to the technicians for subscriptions: but then all was cleared up.

As everyone knows, bribes must be made always disappear, and here is a very subtle way, simple and in its own very ingenious.

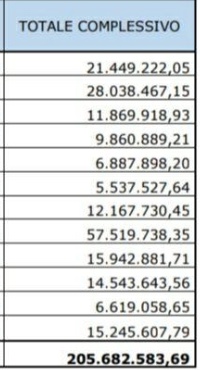

Two technicians, L. and O., are in charge of examining a very important real estate file to check if everything is in order to proceed with the sale of a large complex built by a big company that is now selling it to a state agency. Lawyers, notaries and accountants have already checked what they are responsible for and everything is in order. Now it’s the turn of the technicians: does what has been built match with the project, the specifications, the contract documents, the rules and regulations? If yes, the transaction can take place: a lot of money.

The examination is thorough, pages and pages are skimmed over, and in the end everything is in order from a technical point of view. Perfect.

– Shall we send our check result away? asks O.

– Just a moment, I have to look something, says L.

On the last page of the last document there is a summary table with the total, and this total will be the amount to be included in the contract that a team of experts has already prepared. It’s only a matter of a little while, then everything will be formalized and the deal happily concluded.

But L. looks at the table, and discovers that the total sum is wrong: 2+2 is not 4 but 4.1. Possible? He redoes the count, but it is so: 4.1. General alert.

– Oops! A material error, say the sellers, we’ll correct it immediately.

They make the correction, after which everything is handed over to the notaries and the purchase is concluded. For the buyers, it was fortunate that the file was examined by competent, honest and fussy people like L.: they saved more than a million euros.

Some time later I tell the episode to a friend.

– Do you believe in a mistake? For me it was a bribe. Think about it.

I think about it, and it takes very little to convince me that he is right. It would have been a perfect mechanism: who on earth, after having read a very long and detailed report, would start adding up the last table on the last page? And yet it is on that last figure that resolutions are made and contracts stipulated. Simple as the egg of Columbus.

I would add that L., a very experienced person, probably did not make the check by chance, but because he knew that certain “errors” are anything but rare. And in fact here is a variation on the theme.

One day the members of a large commercial company discover that the shares of the most important partner, Mr. B., a person of international fame (no, he is not Berlusconi), do not correspond to the paid-up capital, but are a little higher, and this does not mean pennies but millions of euros. After due diligence, it is fund that this is the consequence of a small error made at the time of the company’s incorporation: the inadvertent shifting of a line in the table summarizing the shares caused B. to be assigned a different percentage from the one he was entitled to, and, as chance would have it, a rather advantageous one.

The partners: – All clarified, can the correction be made?

Partner B.: – No way!

A very heavy legal battle ensues. In the background, the author of the error is a spectator, a person who is highly esteemed and irreproachable.

But… We know that it’s a sin to think bad, but we guess, isn’t it?

Profitable Rents

One day I had to do some controls in an apartment in a narrow street of the old town.

I go, ring the bell, but no one answers. I wait patiently on the doorstep; sooner or later someone will open. The wait gets long. Every now and then I look up and try again, but in the meantime I notice that the rare passers-by, people from the neighborhood, give me inquisitive and somewhat severe looks. At least that’s what it seems to me.

What is it, what’s wrong? I look at myself, but I’m fine, there’s nothing wrong with me.

Then, when they finally open the door and I can go upstairs, I understand. It should not have been a novelty for that lady to have men waiting to come up to her.

In another case, however, the wait was longer.

One day, in an old apartment house in the city center, the water from the septic tanks leaked and flooded the cellars. It was emptied and the problem seemed to be solved, but shortly afterwards the leaks reappeared. Other investigations, and finally a mason finds the cause: the drain is blocked by a solid conglomerate of … spaghetti.

General dismay: who flushes so many spaghetti down the toilet?

The administrator arranges for inspections; in one apartment, however, owned by a wealthy professional, no one opens. A couple of other flops, phone calls, then finally someone opens: it’s a middle-aged man, in a tank top, stocky, balding beard, belly…. But as soon as we can glimpse the inside, a surveyor, stepping back on the landing, whispers:

– I’m not going in, I don’t want to get AIDS (these were not Covid times yet).

Then everyone heroically enters the apartment. Or rather in the apartments, because each room was set as independent: bed, closet, table, stove, sink, toilet, bidet, TV, and here and there fancy clothes, high heels shoes, wigs, marks of a squalid existence scattered everywhere.

The type of activity of the tenants is evident: each one – male or female? – works in one of the rooms that the respectable owner has adapted as a mini-apartment.

Certainly with profitable rents.

Esprit des Lois and Accessibility for Disabled

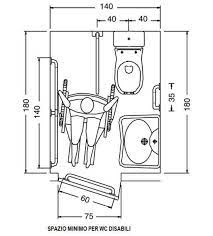

Designing spaces accessibility for disabled people is nowadays a child’s play: the standards are provided by precise lists with criteria, measures, cases, aids and so on; and then on the internet or in CAD libraries anyone can find ready to copy and paste diagrams, overall dimensions, movements, solutions.

A few drops of sweat may wet the temples of the less gifted technicians if they have to modify artistic or historic buildings, or if they have to deal with the rights of others, but little stuff; and you can also enjoy benefits from many facilitated procedures.

Everything okay then? Not really, because even behind, or rather above all the prescriptions and all the formulas, there is always an ‘esprit des lois’ (pardon me, Montesquieu!) that should be kept well in mind by those who design.

The first article of the laws in question provides as a goal of any project to respect the disadvantaged person and minimize any discomfort that may be required; and the first paragraph of the first article prescribes that the condition of disability should not be highlighted more than what is strictly necessary, as well as the efforts that are required to move.

In order to achieve all this, the designer has great possibilities, because he is the one who decides the conformation of places and spaces, and consequently he also has great responsibilities on the human level and the professional ethics. For example, before creating a difference in level on a path used by disabled people, he should ask himself if that difference in level is really necessary.

Examined from this point of view, there are many projects that, while perfectly compliant with the law, cry out for vengeance.

One day a building commission examined the project of a public building commissioned to an internationally renowned architect, a true archistar. The project is obviously very beautiful and is explained to the commission by the delegates of the large firm.

All in order, it can be approved.

However, before issuing their opinion, the commissioners respectful observe that, although all the requirements regarding accessibility have been duly observed, according to the drawings presented, a disabled person who wants to reach the elevators from the street and go up to the floors would make a path of about 40 meters almost all outdoors – that is in the sun, cold, rain, on foot or in a wheelchair, with obvious difficulties and fatigue.

Could that be avoided?

Of course it could, everyone knew it, since they were all professionals: the question was only submitted to express a kind invitation, a polite recommendation aimed at protecting the disadvantaged, even if in some rare circumstance.

But the answer is surprisingly no.

No?

No. We are not changing the project.

But even more surprising is the reason for the no: because any retouch of the facades would compromise the beautiful aesthetics designed by the archistar. The norms are observed, what else is required?

So the facades remained beautiful, to the undying glory of the great architect.