Roman portraiture is one of the peaks of classical art. When looking at the bust or statue of an ancient Roman we feel a strong emotion, because those portraits intensely communicate the personality of the subject, as bringing him to life in front of us again. Art historians explain the techniques, the schools, the Etruscan and Greek influences; but there is an aspect of those faces which brings me, as an architect, along paths that are not those of aesthetics and history of art.

Let’s look, for example, at a Caesar’s portrait: the face appears so perfectly shaved, that not even Mr. Gillette would have objected to; and like Caesar a lot of emperors, viri illustres, important characters or unknown ones.

elf but had his own barber, an expert servant who provided for what necessary: shaving at home meant not only sharp razors and soothing balms, but also hot water for compresses and ablutions, and we can guess that some slaves were ready every day at fixed times to boil water in a pot after having drawn it from some fountain connected to one of the numerous aqueducts that served the city. Alternatively, one could go to the thermal baths, and it is probable that Caesar frequented the best ones; anyway even there everything worked thanks to the aqueducts.

Therefore, Caesar’s shaving, like that of a lot of other Roman faces portrayed in marble, depended on the existence of aqueducts, whose construction presupposed a complex organization and a technical knowledge that no other people of the ancient world possessed; and Romans could be proud of that. In short, those clean-shaven faces expressed a subliminal message of superiority, as: «I’m shaved, and I can shave because we have aqueducts; and if you don’t shave it’s because you don’t have them; and you don’t have them because you don’t know how to build them. You are far behind us.»

So, Caesars’ perfect shave expressed a message of supremacy all the more effective as it was translated into terms of daily habits, of unattainable comforts for the many who lived in remote villages in the forests, and who were not by chance called ‘barbarians’.

And those Roman characters portrayed with a beard?

Perhaps it was due to a habit or a fashion, perhaps was a reference to the origins in distant provinces, or to the military campaigns, because on those occasions it must have been necessary to let the beard grow, for Caesar too. But he didn’t let himself portraited with a beard.

Fragment of an engraving depicting the plan of an aqueduct with the names of the users, the amount of water they were authorized to draw and the hours of withdrawal (From Mommsen, C.I.L., IV, I).

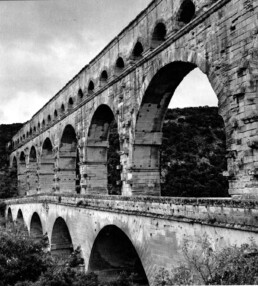

View of the Pont du Gard near Nîmes. Note that in the third order the water conduit (specus) was not made to rest on a structure with large arches like the one below, but on small arches, both for the purpose of obtaining more precise control of the slope during the execution of the specus, both to minimize the inevitable settlements of the structure causing water leaks and to improve the maintenance works.