Birth of the Corridor

It seems that the invention of the corridor can be attributed to the English architect John Thorpe, who in 1597 built a house in London with the first example of this constructive solution that will then be applied in the most diverse contexts.

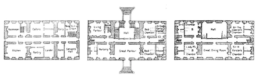

Unfortunately we have no further information on Thorpe’s work, so to explore the topic we must refer to the construction of Coleshill House, an English noble residence built in Berkshire by architect Robert Pratt in 1650, with similar assumptions. This building no longer exists because of a fire in 1952, but its floor plans show that it had a series of rooms on two opposite sides, divided by a long corridor.

Coleshill House was a house of aristocrats, and at the time (17th-18th century) those houses were organized with rooms placed in succession to create scenographic effects to visually give to guests and visitors the idea of the wealth and power of the owners. The most seeked effect was the so-called enfilade, i.e. a perspective suggestion created by aligning the doors of the rooms. In this way they could brilliantly get the aim of represent their social role, but passing through the rooms was unfitted for privacy. Moreover, the owners, in order to enjoy any possible comfort, had to live daily in a very close relationship with the servants, whose pervasive presence gave rise to delicate situations and continuous discomfort. Even if the aristocrats behaved without minding at the servants, as if they didn’t exist, this coexistence was a source of stress and gossip, and not infrequently also of murky stories and violence.

To mitigate these problems the rooms were organized in a progressively greater private use ratio, beginning from halls and drawing rooms closer to the entrances to the more distant and private bedrooms, which were gradually equipped with changing and sitting rooms and boudoirs, thus becoming secluded areas – hence the term ‘apartment’ – reserved for the owners and for those who were allowed to share their intimacy: relatives, friends, lovers. And, of course, the servants who had to be always available when called and disappear when their presence was no more needed. For this reason, paths were created reserved for them and separated from the main ones, with narrow stairways and passages from which at any time, at a bell ring, the servants could reach the masters’ rooms from the kitchens and other rooms of theirs, usually placed in basements or attics.

Naturally these passages were also used for other purposes, more or less lawful and secret, but very busy, as we find in a lot of novels (as Dumas’ ‘Queen Margot’) and movies.

Today we think at a corridor as a narrow and long room used as a passage to give access to a series of rooms in which functions are performed. Now, the corridor of the Coleshill House is a little different, because it performs also as a filter towards pairs of small modular apartments and has inside the stairs of the servants. In short, the functional organization is evolved, but the criteria of the aristocratic residences are still applied, and it could not be otherwise because of the existing social rules to be still observed. However, a line was traced to be followed, even if for a very long path: the separation of servants is in fact still found in the early twentieth century in many bourgeois villas, which have small doors on the edge of the main facades and reserved for the servants who used them without passing in the representative rooms.

So, Coleshill was a first step towards the corridor as we think of it today, but Pratt seems also to have given way to a precise building typology, technically called ‘triple bodied’, which had to get an enormous diffusion due to its affordability in order of functional, constructive and hygienic performances, so that was applied in the early twentieth century for large social housing projects. After the following customs evolution not behaviors were distinguished but functions, and rooms got some freedom in use inside, as long as their access was controlled. As many parents know when their children’s bedrooms have become strictly off-limits.

An aristocratic residence with reception rooms and private areas but no corridors: the Chiswick House in London, by Richard Boyle (1726).

View of Coleshill House in an 1818 engraving by J.P. Neale and H. Hobson (British Museum).

Coleshill House floor plans. In the basement (left) are placed kitchens, cloakrooms, pantries and other rooms for the servants’ works; on the ground floor (center) the atrium with the main staircase, two apartments, a hall, a living room, a nursery; on the first floor (right) a large dining room and four apartments. Is missing the plan of the attics with the servants’ bedrooms. Note that the corridor is flanked by large walls where chimneys are placed; they also keep the apartments warm and support the roof terrace.