What does the Baptistery have to do with the famous question of the horns of Michelangelo’s Moses? Nothing, of course, but there’s a reflection on the choices of the artist that I would share with my readers.

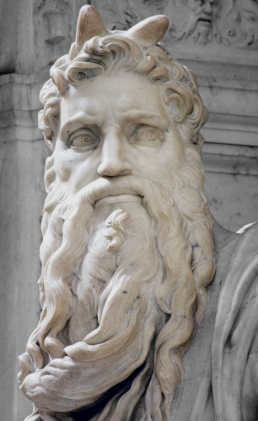

As everybody knows, the Moses of San Pietro in Vincoli has horns on his head, instead of the light rays so frequently depicted that certainly seem more suitable to represent the shine of prophet’s face on coming back from the second meeting with the Lord on the mountain.

But did Moses really have a shining face? On this point, the biblical text (Exodus, 34, 29-35) proposes a difficult interpretation: grossly simplifying the terms of a very complex and obscure question, according to some scholars his face had a terrible appearance, so that, when he realized it, he had to cover himself with a veil.

This uncertainty stems from the hard translation of a key word that in Hebrew can have two readings – ‘karan’ or ‘keren’, that is ‘light’ or ‘horns’ – whose exact meaning must be valued in the context and if it’s to be understood in a literal or translated sense.

But fortunately this thorny problem does not concern us: here we are only trying to understand the reason of Michelangelo’s choice.

Let’s start therefore from the evidence that Michelangelo stuck to the text of the Bible of St. Jerome, and that St. Jerome, between the two possible translations – light rays or horns – chose the horns, writing that Moses, on his return, had a ‘cornuta facies’, a ‘horned face’.

Michelangelo undoubtedly would have no difficulty in modeling radiant and luminous shapes, and a head with rays represented a very common iconography. Finding instead a suitable form to connote a ‘horned facies’ for a prophet without using the special effects we see today, but having instead to model it in a solid and fully convincing form, was a really difficult task.

What horns to represent? Think to any horned species of the animal kingdom, from snails to deer, and you can realize that Michelangelo was as squeezed in a corner. Anyway, he had to mold horns, which would have had a value of symbols; and symbols of this type could offer to malevolent observers easy opportunities to create embarrassment to Christians, Jews and the pope himself.

But he avoided any veiled or even distant reference to a threatening, ironic or even less demonic sense by choosing the least offensive horns: two horns just sprouted, like those of the little goats he saw grazing in the meadows of his Casentino as a boy.

Could he not choose horns? No, since he knew the Holy Scriptures very well, and had not to seem an ignorant, but also because for him sticking to the official text approved by the Church was unavoidable, given that he was working for the pope and that in the occasion he certainly had an expert biblical scholar at his side. Therefore, any possible objection on this point would not have been consistent.

But it could be also have been necessary to face some bad faith criticisms; and in this case I believe – it is only a conjecture of mine, of course – that Michelangelo could also counter them by pointing out a valid argument, i.e. that horns were an appropriate symbol for the leader of a people to conquer a new land.

Let me explain why, starting a bit far away but making the shortest path.

In the circles of Renaissance intellectuals, the myth of the Roman god of the borders, Terminus, was known. In ancient Rome, to move the boundary of a field or a property secretly or without the neighbor’s permission was a major crime to be punished very severely.

But then someone pointed out a quibble: after all, the conquest wars that the Roman people made to the whole world what were they but unauthorized displacements of boundaries? Perhaps the Roman state preached well and raced badly?

In the homeland of law, in short, an embarrassing question was posed.

Then, to get a face-saving, the Romans found a ploy that was a masterpiece of hypocrisy. According to it, they established that when a commander (dux) was appointed to a military expedition, during his performance he became the god of the borders himself, Terminus – the strange god who, as someone perhaps remembers, had a symbolic relationship with the construction of the Baptistery. Therefore, as long as he was on his duty, the dux had the divine power to move the state boundaries, that is, to annex the conquered territories, because the gods of Rome had guaranteed to the Romans the conquest of the whole world.

So, the dux would temporarily become the instrument of this divine plan becoming Terminus; and since Terminus was represented as a boundary pole with the head shaped as a fork, also from the dux head two horns were expected to sprout out; and as it was obviously impossible, they remedied by putting on his head, in ceremonies and triumphs, an oak crown to hid them, and everyone pretended to believe it.

Michelangelo therefore could find an answer even to the malicious objections by referring to classical traditions; and in this regard it seems significant that his Moses’ horns are clearly spreading out like a fork, differently from the normal horns on the skull of goats.