In my course of Distributive Characters of Buildings, to introduce some topics of dwelling I first made the students reflect on a point: that our projects do not only create more or less beautiful things, but also deeply affect the very lives of people.

Before submitting some examples taken from everyday life in our houses – living rooms, bedrooms, elevators, stairs, toilets and so on – I thought of introducing the topic by bringing two extreme examples, one for good and one for bad.

For the bad, it seemed obvious to choose Auschwitz: after all, it was somehow also a particular ‘dwelling’. Naturally, I would have faced such an important and complex issue from a very defined and limited angle, that of the project.

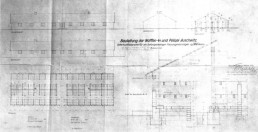

I found a very well-documented book on the subject (R.J. Van Pelt and D. Dwork, Auschwitz – 1270 to the Present), by which I learned that Himmler had chosen Auschwitz not only for the purposes we know, but also to make it, thanks to the work of the internees-slaves, a productive center to finance the activities of the SS. For this reason he had a staff of technicians to draw up urban plans (Auschwitz was at the center of a group of satellite camps) and detailed building projects, and many of those drawings miraculously escaped destruction. From them one could see how the project of this camp had been meticulously articulated according to the teachings of Rationalism of the time, precisely defining connections, green areas, placement of the buildings, functional division of the zones, construction details of barracks and furnishings… in short, everything, even the modifications that became necessary to the crematorium installations in order to face the enormous number of dead.

In these project designs were evident the devices used to destroy not only physically but also psychologically the inmates: for example, at Birkenau had been provided only one latrine for 32,000 women, and it was a small hut that could be used only at fixed times, and to be reached after long queues with feet sunken in excrements. Inside this shack there was a pit with boards thrown across it: on these boards the inmates perched tightly together and often in the grip of dysentery, soiling each other’s rags in a nauseating stench.

Now, the architects and engineers who had designed such a ‘toilet’ could not claim their fairness saying that they were unaware, that everything was casual; and let’s leave aside any talk about the gas chambers, which had punctual and documented building and technological modifications to speed up the ‘work’. In short, the criminal intention of those technicians who had scrupulously used their knowledge to design evil was evident, and I emphasized this in classroom, finding great interest among the students.

Then, years later, I learned that Prof. Van Pelt had been called as an expert in a trial against David Irving, the leading Holocaust denier, and found himself involved in a heated controversy. The deniers in fact sought every argument to challenge the idea of a planned mass extermination, and the debate was getting bogged down in a discussion about the methods with which history is written and the reliability of testimonies and documents. History is always written by the winners, right? – they argued – and even in this case they had gone far beyond the reality of the facts: there was no proof that millions of people had died in the camps, nor that those ovens could reduce to ashes such a large number of corpses. The discussion touched on very technical aspects, and even came to take samples from the walls of the gas chambers, to check if they were really soaked with cyanide gas – the famous Zyklon B – which to limit costs was used very sparingly in doses despite the fact that this dilution involved a lengthening of sufferings.

But a very concrete and decisive argument against the deniers came just from the plans of Auschwitz, produced in court by Prof. Van Pelt, because those drawings demonstrated beyond any doubt, both for the creation of clearly functional buildings, and for the meticulous organization given to the whole – that is paths, functions, flows, dimensions, all studied with the prope manuals’ criteria – the purpose of those projects. Just as the drawings of an engine make a mechanical engineer understand how it works and its performances, so the Auschwitz project, analyzed by any technician, provided a very clear evidence against those who claimed that the extermination camps were just a fake.

If the choice of the most negative example had been obvious, I found myself in a bit of a quandary when it came to the positive one. I thought about the Jacaré School, various places of spirituality, Dr. Schweitzer’s hospital and so on: all examples were worthy of attention, but not exactly in line with what I intended. While searching, I came across a topic that had great appeal, and I dwelt on that, though perhaps a bit off topic: the house of the Last Supper. What did it look like?

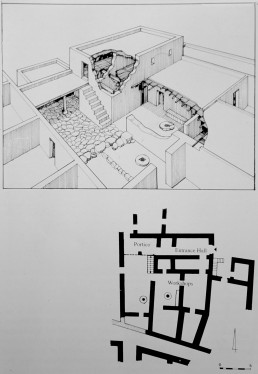

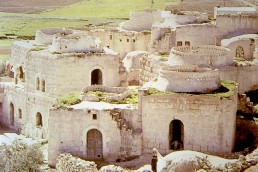

The endless paintings depicting that event are obviously figments of the imagination, but I was interested in knowing something of the building reality. What could be said was very little, and it was obtained by cross-referencing the studies of archaeologists with some hints we find in the Gospels. In a book (Y. Hirschfeld, The Palestinian Dwelling in the Roman Byzantine Period) I found illustrated various types of houses of the time, and also those that had the famous ἀνάγαιον (anàgaion) mentioned in the Gospels: a room on the upper floor, which had a use similar to the living rooms of today and was reached from the courtyard by climbing an external staircase.

This house, which was located in the southwest part of the ancient center of Jerusalem, was the first church, in which the apostles withdrew after Golgotha and where Pentecost took place. The property probably belonged to the family of the evangelist Mark.

The house that hosted such important events was therefore a very simple one, similar to many others.

Because good is made of small things.

(Above) The architects and engineers of Auschwitz in a group photo from 1943 (Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum).

A table from the first Regulatory Plan of Auschwitz, dated June 1941: in the center the main camp with the appeal square, the inmates’ barracks, the prison, the infirmary and the crematorium; on the right the lodgings of the SS and the station above; on the left, the command of the camp, warehouses and laboratories (Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum).

One of the executive projects for the Auschwitz prison barracks. You can see the accurate executive definition of the works to be carried out, which were then described in the specifications and calculations that completed the projects; the originally planned capacity of 550 prisoners for this hut-type was quickly increased to 744 (from Van Pelt – Dwork).

Examples of Palestinian homes similar to those of Christ’s time.