(continued)

11 – The Project is a Person

At this point a question bore asking: how were they able to manage such a complex construction at a work with multiple locations? The answer would require a very long discussion, but let’s look at some of the fundamental points briefly.

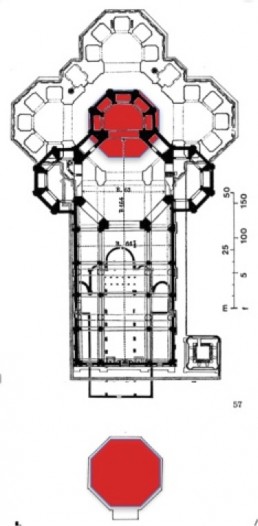

For the contractors it was naturally a vital precondition to the whole work that a very well-defined design should be drafted that did not entail corrections, doubts, or second thoughts, or it kept them to a minimum, otherwise, given the distances that they had to cover, the entire endeavor would have been a failure. And the Baptistry testifies fully to the fact that this is the course that was taken, because it is such a perfect mechanism that it prompts the unconditional admiration of all of the greatest architects of all ages. The design of the Temple did not allow for modifications.

But this design, materially speaking, how was it made?

Obviously, in the ancient world today’s representation systems of technical drawing did not exist, but they knew how to draw floorplans, sectionals, detailed drawings, and they used models, templates, and samples. All of these partial representations together however had to find those who knew how to manage them, and that was the architect. Thus, at the time a draft was not a collection of documents, i.e. illustrated tables and written pages, as it is today. Rather, it was a person, the architect himself, who knew how to utilize the drawings and models that were needed, and he imparted working instructions to those who had to carry out the task. Like a conductor who knows the musical score by heart, he had to have all of the individual operations that were needed to construct the building clear in his mind. He was also ready to explain them to the master builders and to the workers and to find solutions to their problems in order to successfully finish construction according to the established terms of the contract.

The architect was qualified to do so not only on account of his personal skills and his studies, but also because he had undergone a proper apprenticeship with a group of builders or an enterprise. And with regards to the latter, it is believed that the builder of the Temple was of Greek or Middle Eastern origin, given that the greatest centers for the processing of marble for monuments were in the Ionian area, and that he may have moved to Florence in order to monitor the work along with a group of colleagues who had to maintain the relationship between the ones carrying out the work and the material suppliers. Besides this role of supervising and coordination, he was given the task of maintaining relations with those who had commissioned the building, whom he had to answer to about the progress of the work.

12 – The Temple Didn’t Wear Prada

The role of a Roman architect was quite different than what is understood today; or at least, I do not dare to think what would have happened if to construct the Temple the duumviri of Florentia had turned to, as our mayors do, a bigshot starchitect, if at the time there were any. The starchitect would certainly have demonstrated his imagination and his tastes by creating a griffe-masterpiece, made in his image and likeness, that is, according to his personal brand. Thus, today we would have had the Prada or Armani Temple, which is to say a great architectural firm, whose fashion house would have born a recognizable and indelible impression.

Lucky for us and for Florence, for art history and the history of architecture, things did not happen that way. The Temple could not bear the distinctive signs of a singular figure because it had to represent Rome, its history, its culture, its people. It had to be a choral monument: the architect had to have the liberty to express himself as an engineer and as an artist, but also stay within a rigid frame of which symbols to use and which messages to convey.

The form had thus very precise rationales, and it is not an exaggeration to say that it was thrilling to find them brought to light not only in the customary precious texts of Classical Archeology, but also in Roman religious texts. This should not be surprising because in the Roman world the natural and the supernatural coexisted in a perfect overlap, which we moderns find difficult to imagine flowing into the thousands of streams of daily existence, because for us the supernatural is restricted to very limited areas of our lives, or no longer falls within them.

I had another interpretation of the monument that was added to the preceding ones: about the project design.

13 – At the Teachers’ Exam

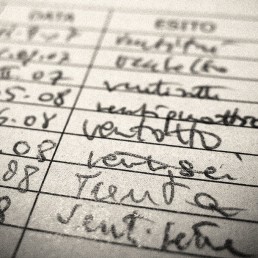

And so, I had found another key to understanding the monument, that of the design, and as a professor of design I couldn’t for one second resist the temptation to imagine how the architect’s exam would have gone.

Here is the result of the imagined-exam.

1st Topic: Celebrate the Glory of Rome

The candidate demonstrates adequate knowledge of the Triumphal Art by proposing a composition based on a central space with a shrine and a trophy. The symbols are expressed with appropriate emphasis and appear to be understandable even to someone who is illiterate. The interpretation in a metahistorical key of the internal space is commendable. The heroic symbols placed on the rosettes of some of the columns are unoriginal.

Rating: Fair.

2nd Topic: Celebrate the Victorious Commander

The candidate proposes to portray the emperor with an equestrian statue placed on a column at the center of the shrine: the composition is correct but not particularly original.

Rating: Satisfactory.

3rd Topic: Design the Hearing Place

The candidate proposes to lay on the floor a red porphyry disc, a normal rota porfiretica, but he enhanced it with a rather original design that visualizes the distance to be kept from the sacred person of the sovereign very well.

Rating: Good

4th Topic: Design the Apparatuses for the Cult of the Emperor

The candidate proposes creating two symbolic events focusing on the projection of sun’s rays in the interior. One consists in capturing, at noon on the summer solstice, the maximum power of the star thanks to a special meridian to be aligned towards the northern door. The other regards the celebration of the victory of the Sun every morning at dawn against the darkness of the night by making the first day’s sunbeams pass through the eastern door.

The committee observes that the proposals are not particularly original because they fall within the prevailing traditions. The installation of a northern meridian seems to be very problematic while the symbolic role of the east door should be highlighted with some elements that emphasize it.

Rating: Rather abstruse, but original: Good.

5th Topic: Ideas for an Augury of Prosperity and Peace

The candidate proposes to not modify the integrity of the space of the Temple with inappropriate additions, but rather to create, for the occasion of the inaugural ceremony, a temporary apparatus centered on the symbols of the god Terminus. These are suitable to express the concept of the hoped-for resistance of the empire in the face of future invasions in a manner that is comprehensible to all.

Rating: Satisfactory.

The candidate is approved with a grade of 28/30.

(followed by the date and illegible signatures)

Not the most brilliant score, as one can tell, but those professors with little open-mindedness (they exist, you know?) made their assessments by basing everything on the tunnel-vision of formal art, and probably they were also a tad envious of the prowess of the candidate. It happens.

It’s just as well however that they didn’t reject the idea of Terminus: without Terminus the present study could not have begun.

14 – A Sequel with a Happy Ending, but…

Having passed the test, was it the research over? No: another one started about the second life of the monument. A sequel.

Setting: a prosperous small town, salt of the earth people, dedicated to the work.

Plot: the construction of a new look that renders the protagonist, a former Temple of Mars, presentable. But presentable for whom?

Let’s have a look (in order of appearance).

For the Catholics? Impatient, they make it their own right away, but they are soon kicked out.

For the Aryans? They take it over by making use of political protections, but they don’t last because a war breaks out.

For the Byzantines? They occupy the city in the midst of fierce engagements with the Goths: they have other things to think about.

For the Goths? On account of superstition, they avoid Florence remembering of how badly it went for Radagaisus.

For the Florentines? After the war they have eyes only for weeping and they are tyrannized by the people of Fiesole.

For the Lombards? Tough guys, imagine that.

For the Franks? Occupying forces.

For the bishop? Gone for centuries.

So, for who then?

The protagonist, our Temple, is a foundling worthy of a Dickensian novel by now. No one is willing to claim ownership and rights, those who have power in the city would want it for themselves because it’s beautiful and gives prestige, but they don’t spend a cent to maintain it. They don’t even know what to call it, because it’s not a Baptistry, or what do to with it exactly: its religious use is not exclusive, a little bit of everything is done there, there is a great deal of confusion.

The sequel is boring, nothing happens, its viewership crashes. It needs someone that can really boost its ratings. And at last, here he is: someone powerful, cultured, and who loves Florence. It’s the Pope, what more could you want? And Pope Nicholas takes action: he decides on the exclusive use of the baptistry, he finds sponsors who have the money, and he launches a works and decorations program. Long live Pope Nicholas.

Everything’s nice and clear. Except for one thing: if the Temple officially becomes the baptistry of the city, the small and clumsy Santa Reparata cannot put itself forward as its cathedral. As long as their roles are different, it’s okay: otherwise, the contrast is merciless and Florence makes a ridiculous impression to those who come through on their way to Rome, to say nothing of a comparison with Pisa. However, the decision is made. Even if they will have to construct a more beautiful and greater cathedral, and even if this will mean an enormous expense, the Temple of Mars becomes the Baptistry of San Giovanni.

Thus, the work begins, but without realizing that the new cathedral would have to have a dome the likes of which had never been seen, and this could have meant disaster.

But luckily, we know how things went in that.

15 – At the End of the Movie

So, what at the beginning seemed like a silent movie had finally found its soundtrack. We got a complete explanation even for what appeared inexplicable, or what many had tried to explain in every possible way, even with mental contortions very close to the absurdity. Moreover, the legend of Mars was also explained, a legend born in tragic circumstances and that had the Temple at its center. It is on account of these that we can explain the deep love of the Florentines, who saw in their Temple-Baptistry the testimonial to their misfortunes.

The achieved results opened to many possible research pathways, and it was depressing to think how the insistent idea of a medieval monument has been a waste of time for those who study art and history, who teach, and who love Florence.

We discovered that in the heart of Florence there is a building that is the only one of its type to reach us intact and which could be studied in a new and broader perspective, even considering that, since the three-quarters of what lies beneath its floor still remains to be excavated, many other intact and very interesting finds can surely be find out, as burnt remains of fruits and harvests that could speak about the cultivation practices of the time, or samples of mortars that could be submitted for radiocarbon dating and compared to those from the upper walls. There are many research questions that could be asked, and with better expectations than those for example that were had when they went to find the remains of Monna Lisa in the lost church of Sant’Orsola.

I thought this stimulating scenery of new researches could interest those who study the topic, but I was wrong. Officially the Baptistry remains Romanesque: a history that does not hold water continues to be believed in.

But can we mean that it has turned out to be a remarkable tall tale? By now, how can we trust in those who say that the baptistry is Romanesque if they, to prove it, need to rewrite the history of art anticipating by few centuries the Renaissance? This upending all the criteria used and shared thus far seems like wanting to maintain that the sea came into being because of the fish, and not vice versa.

In the end, as we have seen, the chronicles can explain everything in a way that isn’t contradictory. Following them one can get to the top of the Baptistry: it is a hard climb, but from up there we can see a most beautiful panorama. All those who believe that the building is Romanesque don’t know what they’re missing.