Premise

The following articles concern my research on the Florentine Baptistry. It is a complicated topic, and I relate here what I have to say about it. I do not claim to have it all figured out, and I have probably run into some mistakes: bear with me.

In any event, I think I am right in essence for the simple reason that my thesis is in agreement with the historical chronicles of ancient Florence: because it is not obvious why the Florentines would tell tall tales, even if they mixed fanciful elements into their stories.

Please excuse me also if you find some explanations or some criticisms of others’ theses a little pedantic, but for those who are not familiar with the topic I have to give some background information.

A synthesis of my research on the baptistery can be found in the little book “The Baptistery of San Giovanni, a Florentine Enigma. Studies, Legends and Evidences from Dante to Ken Follett” (Pontecorboli ed., 2019, p. 88), cited in the page ‘Scritti’ of this site.

1 – How I Fell into a Black Hole

Everyone is familiar with the Baptistry of Florence, the beautiful San Giovanni loved so much by Dante, and it is obvious to all that the baptistry is a masterpiece of Florentine architecture. In my opinion none of that is true: it is not a baptistry nor a Florentine handiwork, and those who would like to know why can read what I’ve written on the subject. Here instead I relate how I came to such a bizarre conclusion: a long journey often marked by chance.

It all began many years ago, when, during the discussion of a thesis in Architecture, Prof. G., the president of the committee, interrupted the candidate who mentioned venturing into the topic of the origins of the Baptistry: “Look, forget about it, this is a problem that quickens the pulse.” The poor soul made a quick about-face, and he did manage to graduate, but that rough brush-off by Prof. G. made me pause and reflect. So – I thought – in the center of Florence, and at the heart of its history and art, there is a very deep black hole, in which who knows how many explorers have been lost.

I certainly couldn’t have imagined that I would find myself becoming one of them, but it happened like that.

One afternoon while I was on a street in the city center that I don’t usually walk down, I discovered a second-hand bookstore that had in the corner of its window display a little yellowed booklet that sparked my curiosity: Terminus – The Boundary Markers in the Roman Religion. This is how I made the acquaintance of this very strange god – Terminus indeed was a god – whose function was to stay planted in the earth and to do absolutely nothing. Explaining why the Ancient Romans, a people with common sense, had conceived of such an anomalous divinity would be a discussion that holds many surprises, but also one that would take us far from the point. Here it is sufficient to say that, as I would soon discover, the key to solving the problem that “quickens the pulse” lies within the myth of this character.

Some months passed; then, one day when I was sick at home and reading Villani’s Cronica for fun, I happened upon the part where it says that, when the Baptistry was a Temple to Mars, its dome had an open at the top like that of the Pantheon, even if smaller, and that that opening was made so because the statue of Mars that was underneath necessarily had to remain “uncovered to the heavens.” This absurd explanation piqued my curiosity because it is blatantly obvious that using the needs of a statue to account for the creation of an opening, from which downpours that drenched the walls and drafts of air that cause bronchitis and colds could enter, is a bunch of nonsense worthy of Lewis Carroll. Besides, Villani could have easily invented something more plausible, for example that the architect wanted to imitate the Pantheon. Therefore, if he had braved the ridicule, it must be because he had copied that piece of information from a very trusted source, probably a text kept in the city archives that he frequented.

And indeed, his source merited that trust because that information had a basis in a truth that Villiani was not familiar with, but that I then was, thanks to the yellowed booklet from which I had come to know that being “open to the heavens” was precisely a feature pertaining to the god Terminus, as unique as a fingerprint or a barcode. Could there be a mistake? No, because two lines down Villiani added that the statue should not be moved, otherwise Florence would experience terrible upheavals, and this was also another unmistakable aspect of the immobile god, because if someone moved him, he would take it very badly and the end of the world would ensue.

From all of this I concluded that an ancient text consulted by Villani referred to the existence of a connection between the statue, the god Terminus and the Baptistry, and indeed with the design project for the Baptistry itself because leaving the dome open must have been a decision that involved architect, committee members and builders. It must also have dealt with a different case than that of the Pantheon, for whose great oculus no one had ever proposed the idea that it was made for a similar kind of reason.

It seemed a logical conclusion to me.

But did any of this make sense?

2 – Not a question for TV Game Shows

Driven by curiosity, I then began to brief myself about the “Baptistry question,” and very soon I realized that actually it was a topic that quickens the pulse, because it was the object of discussions that had been ongoing for centuries and involved legions of battle-hardened scholars.

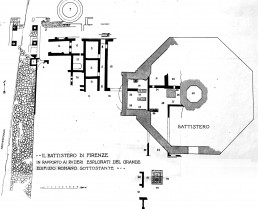

In a nutshell: the classical appearance of the monument makes one think it is Ancient Roman, but the prevailing theory today is instead that it is Medieval because excavation underneath it revealed the remains of Roman houses, and their presence made it seem logical to deduce that the monument was constructed after the destruction of ancient Roman Florentia.

The endeavor to find it a plausible collocation within the Medieval period put enthusiasts on the matter to the test however, as those who have written everything and the opposite of everything about it, until finally today’s leading experts have said enough: we do not know how to say so precisely, but the Baptistry must be Medieval, trust us. This is as much as one reads in school textbooks, in disseminated texts, in glossy publications, in encyclopedias, on the internet, in travel guides, in hotel brochures, on chocolate bars wrappers, everywhere, except on TV game shows, because the research staff on duty would not know how to judge the answer of a contestant, whoever this happens to be.

Doubts therefore remain, they have only been swept under the rug, where they are in good company with a very strange legend that connected Mars not only to the Baptistry, but also to the city: as Dante reminds us, Mars was the “first patron” of Florence with sinister powers. What was the meaning of that legend? According to scholars it was all a fable; however, there must have been some reason if in Florence everyone, literally everyone, the general populace and intellectuals alike, believed in it for centuries; but what was the reason? To find an explanation, someone advanced the hypothesis of an obscure deep political-cultural plot tipped in the Medici’s favor, but the idea has not garnered the interest even of those who write fiction.

3 – Like in a Silent Movie

Thus, as I mentioned before how overwhelmed by curiosity I was, I thought to return to the monument with the wishful thinking that I would, perhaps, find some I don’t know what kind of clues there that had escaped everyone’s notice.

Having asked for the necessary permission, I visited it from top to bottom, which also elicited the curiosity of the security guards, whose way I was always in. I was underfoot so much there that one day while I was going all the way up to the lantern (an excursion that is not recommended for those who suffer from vertigo), one of them asked me politely what I was looking for. I explained that I was a teacher in Architecture and that I wanted to make a study of the Baptistry: “Oh, I like to walk with those who are studying it, no one’s ever visited up there.” I found his observation a bit disquieting: how many books had been written without first-hand knowledge of the monument?

I was getting less than nothing from my visits however: I observed, took notes and photographs, but I still couldn’t understand a thing. The beautiful San Giovanni was like a silent movie whose plot escaped me. Only a few particulars about the lantern seemed to confirm that precisely on top of the dome at one point there had been an opening, but this was not new news, because no one had put forward any claims on the matter. As for the rest, utter darkness.

If the walls remained stubbornly silent, however, a vague hope came to me from mythology, because now, to the long chain of stories and legends that connected the city, the Baptistry, and the god Mars, another link had been added: Terminus. His role in the matter was still to be determined, but it was certainly an important part because he had left his tangible seal on the oculus of the dome.

I then moved my attention to the legend of the statue of Mars, and here a small light seemed to appear. Indeed, connecting it with some aspects of the myth of Terminus whose story would take too long to tell if I stopped here, I suspected that the connection with Mars was not explained by the pagan cults, but with some “martial” event. And in Florence in 406 a truly epoch-making event occurred, when the Roman army led by Stilicone stopped the barbarian invasion led by the gothic king Radagaisus who passed here on the way to sack the city of Rome.

Was it possible that the Florentines had erected a monument to remember that victory?

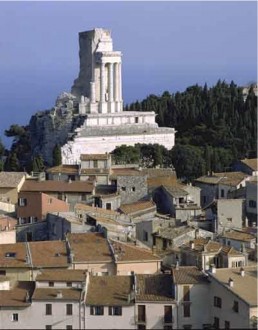

4 – The Dangerous Temples of Mars

In order to answer this question, I had to conduct some research about the Roman monuments erected on the sites of victorious battles. How were they made? Were there rules or models to follow? Where were those that remained? I found all of the answers in Classical Archeology textbooks. These monuments conformed with traditions that constituted the ideological bases of the Triumphal mode, the official imperial art of Rome. Although they used symbols and rites that could result in the implementation of different shapes and consistencies, from sculptural compositions to grand buildings, essentially they all conveyed the same message: divine favor for Roman arms, inevitable destiny of universal dominion of the empire, grave consequences for their enemies or those who resisted and opposed them. The Romans, as is well known, were not much for subtlety.

The nucleus of these monuments was always a Trophy, a word which today makes one think of winning a competition. For the Romans, however, it expressed altogether different concepts: the Trophy was believed to capture the deadly fury that was unleashed in the heat of battle, and for this reason they were erected where that fury, for some inscrutable divine will, had resulted in favor of the Romans, to be redirected against other enemies. Therefore, a sinister enchanted cloak hovered over these monuments, and during the Christian era it resulted in their systematic destruction because they were considered to be sources of witchcraft.

5 – Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde

In light of these clues, I ran to check if the architecture of our mild San Giovanni could be concealing the characteristics of a terrible Triumphal monument, and it was surprising to find that it had them all. Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, basically.

The first test regarded the most macroscopic anomaly, meaning the dimensions of the monument: they were completely oversized for what was supposed to be the baptistry of a small city, but a perfect fit for a symbol of the power of the Roman Empire, there was no doubt. Like a snowflake dissolved by the sun, it was resolved in this way an architectural absurdity that had been irreconcilable if considered in terms of a normal baptistry-cathedral relationship (what crazy bishop or megalomaniac could have conceived of a baptistry like that?), and even explained that atmosphere of power, rather than a pious and heavenly one, that can be felt inside the San Giovanni.

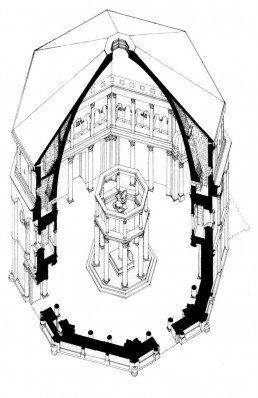

Even the central plan, the dome and the four directional doors (because originally there were four: here one would have to digress, but we must go ahead) turned out to be perfect for a structure that had to “fire” the fury enclosed in the trophy in every direction around the horizon. And if there was a war trophy in the center of the monument, one could also understand what the two massive foundations found in that location were for. A square plinth and an octagonal ring around it, supported one the statue of Mars and the other a round of columns. In the center of the building originally there was indeed a shrine, and not a great baptismal font. This is also because this font would have presented a slew of constructional incongruities that any builder could have proven convincingly to a whole auditorium of professors without them raising any objections.

There I jotted down a few sketches and I made a rudimentary photomontage, and at last the image of the original interior architecture of the Temple appeared to me – an image of power and full of meaning. Now the Baptistry as it is today looked like an empty, incomplete space, like a shell without its pearl; actually, like a weapon of war disarmed.

(continued)

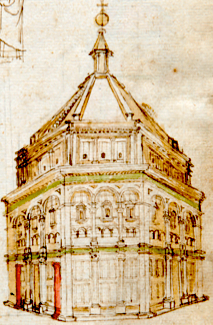

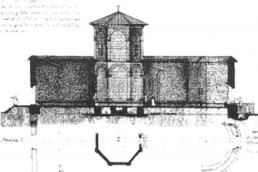

Above: The Baptistry of Florence – drawing from the Rustici Codex (Library of the Seminario Maggiore Fiorentino)

According to some scholars originally the Baptistery was so.