(continued)

6 – They Were not Barbarian Stormtroopers

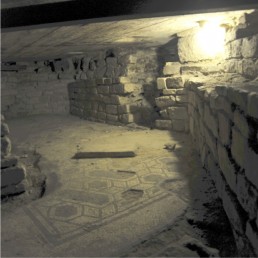

All of that made sense. Therefore, was I on the right track? Yes – actually no: I still had to answer the question of the remains of the Roman houses. I went again to bother my caretaker friends, to reread the reports on the excavations, to look with a magnifying glass at the photos of the findings, and in the end my eyes opened. I ran to the basement of the Baptistry to check, and it was just so: no destructive fury of barbarian Stormtroopers, the houses hadn’t been destroyed but meticulously demolished. The same result, but with a fundamental difference.

Could it be possible? This meant in fact that the Temple had been constructed on a built-up area, while the houses were still erect and lived in, and they had been demolished to create a space for it. Another mystery to solve, and if I didn’t, all of my hypotheses would fall like a proverbial house of cards.

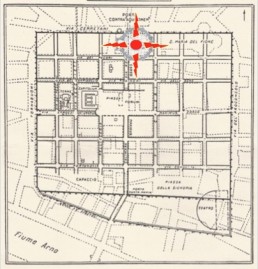

Consequently, I anxiously resumed browsing archeology texts, and in them once again I found the solution. A trophy should be placed such that it faces any incoming danger: in Florence, therefore, it should lie close to the northern walls, in the direction of the mountain passes leading towards Mugello valley, where Radagaisus had come from and where new enemies could still appear. And not only that: the trophy had to be made within the city walls, so as not to create a useful stronghold for a besieging force, and yet be as close as possible to the Northern gate because just outside of it the Mugnone creek flowed, which was the water way used to bring in loads and marble that had sailed up the river Arno.

So that all was straightened out.

But could the city officials truly impose such a choice? Here the research branched out to topics that regarded the ownership of the soil of the Roman colonies and of that area in particular, and the urban layout of Florence at that time, but I found elements of consistency among these subjects also. Everything fell within the perspective of an exceptional intervention, one of those that today are called ‘supreme emergency’, and are implemented in extraordinary circumstances. This was also demonstrated by the fact that that section of the wall showed signs of a work done in haste.

7 – Terrible but Human

By this point I seemed to have arrived at the clarity I had been looking for on the matter. The Baptistry could be considered a fully classical monument, and the theory of its Medieval origin could be thrown in the trash bin with the support of its pivotal argument reduced to crumbs. Entire libraries could be tossed out.

Obviously, that didn’t happen. Those in the past were not, but today’s scholars are all in favor of the Medieval timeframe, and my ideas have certainly not troubled their sleep. Nonetheless, it was important to me to see where my research would take me, and that which was emerging was a convincing, linear explanation, and – a very important issue – entirely in agreement with the historical chronicles. Once the embellishments and works of the imagination that are inevitable in stories that have been passed down orally from generation to generation have been taken out, it turned out that essentially the Florentines were not telling tall tales.

Everything all set, then? Not at all. Terminus, the immobile and silent figure who had started it all was still waiting for an answer. In this setting, what part did he have to play?

He had a part to play for sure, because Terminus, the ultimate symbol of stability and stillness for any Roman, was at the center of the wholehearted, touching message of auspice and hope that the monument had been entrusted to deliver to eternity. Thus, the Temple was not only a war memorial and a threating and powerful symbol, but also the depository of a choral and deeply felt augury for the fate of the people, the city, and the empire. And this ‘human’ aspect of the terrible tropaic monument explains the Florentines’ strong connection with it, which went beyond that of art and beauty, because the citizens remembered that within that monument a little flame of hope was lit that would not be extinguished, no matter what. But before I can explain all of that I have to open a short parenthesis about what happened in Florence in the days of Radagaisus. I warn you that I will use a dash of imagination, but the essence of the story is provided by reliable historical references.

8 – Martian Chronicles

When the King of the goths came south from Mugello valley leading an enormous horde and preceded by a well-deserved reputation for cruelty, Florence must have been laid low with hysteria. A few more days and the city would be overrun, houses would be ravaged, and the inhabitants either killed or taken as slaves. A nightmare. Instead, general Stilicho arrived at the last moment leading troops from as far away as Gaul and everything was settled in an ending that anticipated that of the movie ‘Stagecoach’ by fourteen centuries. It seemed miraculous, and actually they truly believed it was a miracle: prayers and thanksgiving of every kind rose to the heavens – while on earth they lashed out at the prisoners.

Stilicho also had very earthly concerns. His enemies were plotting against him in the Senate by influencing Emperor Honorius, and so he thought to flatter the soft young man by crediting him with the victory in a grand celebration. In this way he would also motivate the army, which was composed of disparate and ragtag troops (many of Radagaisus’ own soldiers took the opportunity to enlist), troops who needed to believe in the great destiny of Rome not so much for high ideals as much as for the hope of loot and plunder. In this way, Stilicho filled the pockets of his soldiers right away by selling thousands of prisoners into slavery and promoted a triumphant celebration leading the troops through the city where he had put up in a hurry a triumphal arch. Then he proposed to the Florentines that they erect a majestic monument, and quickly, as if he had premonitions of the sorry end that he would meet two years later. The idea found immediate consensus (and who could object?), also because the city was a settlement of former soldiers and certain traditions must have still been very much alive.

The chronicles relate that he contacted the greatest builders of the empire through the senators of Rome, and that is in accordance with the times, besides being perfectly logical. One had to trust those who knew how to do these things, and there were people in Rome who had contacts throughout the political sphere and that of important building contracts. Florentines were directed to them by the same Stilichoe (or perhaps by his wife Serena, who was well-connected: who knows?) and they asked for the most beautiful structure that could be made and guaranteed to cover the expense. Because here was the weak spot in the whole enterprise: money. Stilicone did not have it, and Honorius didn’t either. The Florentines on the other hand mustn’t have been doing badly, and thus, bleary-eyed with enthusiasm, they underwrote a substantial contract. It was a real godsend for builders in a time of total crisis in public contracts, but it was a trap for the inexperienced settlers.

There were all of these preconditions for a building scheme on a grand scale, in which everyone had a part to play, including the emperor who was unperturbed by the conflict of interests in supplying marble from the quarries he owned. And the Florentines, who had agreed to pay, paid dearly for it.

Ultimately the structure was truly the most beautiful that one could wish for, but very costly. By observing with the eye of a worksite surveyor the sequence of the improvements that were made, one can understand very well that the later ones were torn down, and that means that things were going badly financially. All of the estimates had been exceeded and now the coffers of the city were practically empty. But with a bit of good will they managed to bring the Temple to completion: it would take about twenty years, and we can go ahead and compare that timeframe to today’s.

9 – Chatters from Behind the Fences

Given that the surveyor’s gaze looked like it would work perfectly for me, I thought I would use it in order to extend my inquiry into the very straightforward issues of the worksite and the contract. This was an endeavor that could be undertaken because the monument is largely intact, the fruit of a unified project with few and minor modifications. Thus, I thought to cross-reference information from the analysis of the structure, the finds of the excavations and a few hints of the chronicles (hints that surely echo the chatter from behind the fences of the sidewalk retirees who passed the time by criticizing what the builders were doing) with the provisions of the contract and the worksite procedures, which are, broadly speaking, the same as those of today, as the ancient clocks measured time with the same criteria as modern ones do.

Thus, like a carpenter who thinks about the kind of hammer he’ll use to drive a nail in as well as the kind of wood where it will be stuck into, I tried to place each fact in the working context it could be connected to and test it for consistency. It was comforting to observe that the result indicated a coherent picture. Finally, the walls began to speak, and in order to listen to them it was enough to tune oneself in to the wavelength indicated by the surveyor: the series of procedures that are done in order to build.

First there was the contract: and from historical events, as we have seen, one could broadly infer how things went.

Then there was the building company aspect: it was certainly a massive undertaking given the time restrictions and the complexity of the work organization, and it proved itself to be very well set up, and not just for making beautiful things, but for being able to manage a contract long distance, in multiple locations, and coordinate timeframe, transportation, supplies, production, designs, workforce, payments.

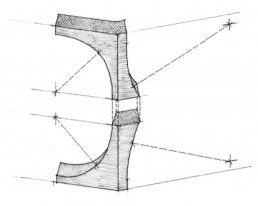

At the heart of the entire operation was the design, which functionally had to be drafted in harmony not only with those commissioning it, given their power and their particular needs, but also with the business side of things, because it was based on the draft that supplies, production, and transportation needed to be organized. The design was therefore not just a masterpiece of aesthetics, but also of proficiency.

In short: the Baptistry-Temple mustn’t be seen solely as a masterpiece of architecture, but also as one of the entrepreneurial and organizational capabilities of a grand undertaking from the ancient world.

It was for this reason that I was very cautious when someone would let me know about the results of a new examination from samples taken with some sophisticated instruments: it only revealed the naive enthusiasm of those who think that one single data-point could possibly resolve such a complex problem. A similar methodological strategy is to be avoided absolutely, and if one happens to come across it, one must think it was due to simpleness, ignorance, or bad faith.

10 – With the Surveyor’s Gaze

So, putting aside the aesthetic and artistic assessments, I fell into the role of the worksite surveyor once again, and I tried to reflect on the task that the architect had had to face as the responsible for such a challenging work. It was logical to think that he had taken into account the fixed obligations of the procurement contract as he made his choices. Bearing this in mind, I found the fact that he had employed Grecian marble significant. It was a choice that didn’t seem to be made on account of aesthetic considerations because similar pieces of marble could also be found in Tuscany, but rather due to factors of operational expedience, such as those of cost and the reliability of trusted suppliers.

This confirmed that it was a contract that was managed far away from Florence, by contractors who were able to handle large orders of worked marble, transfer materials and labor, to organize, to inspect, and to provide accounting for. All of that was consistent with what had been related in the chronicles: “They sent a mission to the Senate in Rome and asked that they send them the most expert master builders that were in Rome.”

Even archeology texts confirmed that my hypotheses held water, but when I went to verify them with what the monument revealed in reality, more questions steadily emerged. Had the claddings been completely worked at the quarry or were some parts also done in Florence? And did the workforce also come from far away or was it partly local?

Some clues seemed to suggest a collaboration among expert workers from outside the city with local workers, who were lower level and guided by the more expert ones. And such a good architect could not have not taken these conditions into account when he was drafting his design. Perhaps the extensive use of geometric designs in the cladding could have been considered the most suitable for practical reasons, given the difficulty of assembling them long-distance.

Furthermore, some details of the cladding reveal an accuracy and refinement that could only be explained by the work of very skilled hands under the direct control of expert eyes. The enterprise must have relied on trusted laborers for such delicate work, as on the other hand it was logically expected in such a context. Many workers must have remained in Florence for a long time, actually for forever if one thinks about that suburb by ancient origins, which would one day be named “of the Greeks.”

(continued)

The Temple of Mars as a magical sentinel to defend the city.

Basements with Roman finds.

The Roman god Terminus.

Ivory portraits of Stilicho (left) and emperor Honorius.

The probable quarries of the marbles of the Baptistery.

Can it be believed that it was a Roman decorator who crafted this small masterpiece of geometry?